Claire Golomb is a Professor Emerita of the Department of Psychology at the University of Massachusetts. For over 40 years she taught courses on child development to undergraduate and graduate students of psychology. Her research during those years focused on symbol formation in child art, make-believe play, story construction and the role of gender in those domains.

Here she answers some questions about her new book, The Creation of Imaginary Worlds: The Role of Art, Magic and Dreams in Child Development.

Tell us a bit about your background, and how this book came about.

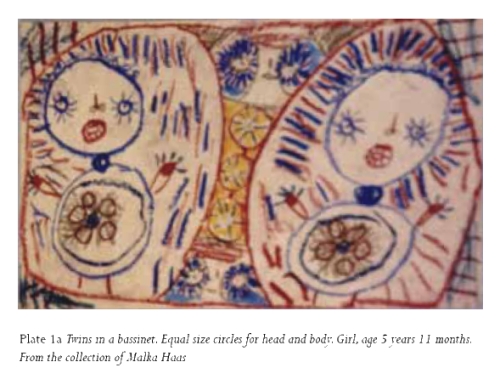

My interest in child art is of long standing, dating back to my graduate student days and work in a mental health setting. Since that time I have done extensive research in the development of child art and make believe play, and published several books on child art and artistic development in gifted children. As an intrinsic aspect of my research I have been enable to create extensive collections of children’s drawings, paintings, and sculpture some of which are reproduced in the current book.

I can date the immediate impetus for writing this, more comprehensive book, that encompasses child art, play, dreams, daydreams, stories, and magic in child development, to the treasure of several extensive collections of children’s art work, poems, and stories which I had the good fortune to review. The thoughts and feelings of the children, their interests, worries, wishes, and hopes could be clearly heard and seen in the different forms they found expression over the childhood years. There is continuity across the different domains of art, play, imaginary playmates, daydreams, stories, and magical thinking, all of which engage the child’s creative abilities and efforts to understand his or her world.

Why do children create imaginary worlds? How does it help them to understand and deal with the real or external world as they grow into adults?

The creation of imaginary worlds in their diverse forms is a uniquely human capacity; it is the ability to go beyond the concrete “here-and- now,” to represent the world as it is but also as it might be, and indicates an early capacity for abstract thought. Being master of an imaginary universe (in art, play, dreams, and stories) can be a source of great satisfaction as it empowers the child, gives expression to often vaguely understood feelings, provides compensation for feeling helpless or powerless, and joy for having invented a world on its own. It provides avenues for gaining a better understanding of the physical and social world and expands the child’s conceptual and emotional horizons.

What is your take on the Imaginary Friend?

They are quite widespread, provide an outlet for the child’s social and emotional needs, and are eventually outgrown or transformed into characters that play a role in one’s daydreams.

What do you think are the implications of your studies for education, the family home and society in general?

The different domains I discuss in my book engage the child’s creative problem solving capacities, and foster development in the child’s cognitive, social, and emotional competencies.

Read Claire’s article ‘The Importance of Fostering the Creation of Imaginary Worlds.’

Copyright © Jessica Kingsley Publishers 2011.