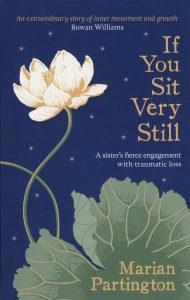

Marian Partington’s sister Lucy was kidnapped by Fred and Rose West in 1973. In 1994, 21 years later, her remains were found in their basement. If You Sit Very Still is Marian’s response to this most traumatic of losses and her journey away from resentment, towards forgivness.

We spoke to Marian about the process of writing such a unique and intensely emotional book.

Marian, you wrote an essay on Lucy’s disappearance called Salvaging the Sacred in 1996. What motivated you to build on this, and to write If You Sit Very Still?

The essay was published in the Guardian Weekend and there was a huge, generous unexpected response which somehow changed me and honoured my continuing purpose. There was a hunger for meaning and wholeness that resonated within me, surprised me. It felt urgent and vital. There was no turning back. I felt heard and understood and realised the necessity of continuing to grapple with questions that wouldn’t go away; to stay true to this unravelling, wherever it may lead, however long it would take and to continue to write. The question of how to live with less harm, how to deepen our compassion in the wake of human atrocity, continues to challenge me to the core. It is upon this that I build.

Your language throughout the book is both lyrical and unflinching in its description of the events of Lucy’s disappearance. It’s a very powerful narrative. How did you feel while writing it?

Finding words, finding a voice was almost impossible at times, yet remaining silent was not an option. If I had tried to carry on with no words, trapped in the frozen silence, I would have allowed death. The words that arose within me came from an instinctive need for a terrible truth to survive, a bearing of witness, a speaking by proxy in the face of unspeakable demolition. So writing became a way of allowing myself time and solitude to experience my grief and to face the unbearable pain of what had happened to Lucy. Each word felt like a rung on a ladder leading from a deep pit. It felt empowering and honouring of our shared love and study of English literature to write. It felt as if we were raising the register through the grace of the words that arrived. It felt as if we shared a sacred realm. I felt blessed and guided.

Lucy converted to Catholicism before her disappearance. Years later, you joined the Religious Society of Friends (Quakers) and spent time in Buddhist retreats. What part has faith played in your journey to forgiveness?

It felt significant and hugely challenging in a way that was ‘beyond’ any formal religious faith. Lucy ‘disappeared’ five weeks after she was received into the Catholic church and we found out five weeks after I had joined the Quakers, twenty years later. I remember thinking that if there was anything of value in a religious faith it needed to show up now. Shared silence was important. To allow what lies within to surface and to be transformed.

I made the vow to forgive the Wests after a seven day silent Buddhist retreat. I realised that this would be the most creative, imaginative way forward, but I had no idea what it would involve and how it might come about. My faith was to trust that I would be shown a way. I call the religious words around this inner work ‘barnacled’. ‘God’, ‘sin’, ‘repentance’, ‘redemption’,’ forgiveness’- these words feel encrusted and clogged up with ‘aeons of piety’. But to travel within religious communities informed by teachings that aspire towards deepening our capacity to love and feel compassion and to know and live with wisdom has been essential to becoming less self-centred and more open to a greater whole. I have grown towards knowing our interdependence and our connectedness and the need to remain open to whatever arises and to learn from that. I feel deeply grateful for all that travel with me, for those who unpick their deluded selves and work towards our ‘true nature’ which is at the heart of ‘this great matter of life and death’.

You comment in the book that our society ‘suffers badly from a fear of the reality of death’. Do you feel as though you’ve come to terms with the reality of death?

When I cradled and wrapped Lucy’s bones I faced mortality in a profound way. It was unavoidable and awakening. I felt deeply grateful to be alive. As I grow older and was recently seriously ill it has become more important to reflect upon this reality every day. I feel that there is a gentle, tender, vast, subtle energy that is truly where ‘time intersects with eternity’. Recently I was convinced of this and knew that it didn’t matter if I lived or died. I am exploring the reality of radical helplessness (my next book!) and the need to surrender in the face of death and to embrace every moment.

Dreams play a very important part in your journey. The structure of the book is based on the medieval dream poem, Pearl, and you highlight five major dreams as signposts towards the act of forgiveness. How did you interpret these dreams as particularly significant?

All I can say is that the dreams felt ‘real’, almost more real than everyday life. They needed to be faced, heeded and integrated. They led me to reflect and act with confidence. I knew there was a truth in them that could not be ‘thought’. Maybe they came from ‘the collective unconscious’. They were compelling and profound, as if they were drawn from a deep well of creative imagination. To finally realise that the book that Lucy had in her bag the night that she was abducted from the bus stop was the ‘shape’ that I needed for this book (after sixteen years of writing!) – this fills me with pleasure and gratitude.

In many cases, it is the perpetrators who are remembered, more so than the victims. How does that make you feel, and why do you think that is?

Yes, I think that this was and continues to be something that drives me to speak for Lucy (Primo Levi called it ‘speaking by proxy’) and to reclaim her as my sister from the labels ‘missing person’ and ‘West victim’. The need to find the words, carefully, so that Lucy can live in people’s minds in all her complex, fiercely intelligent beauty and aspirations was involuntary. I couldn’t just leave her ‘out there’, sticky and stained by the media representations. I felt sad that my energy could not extend to doing that for all of the ‘West victims’, but I try to at least name them when I can. Eventually I realised, through painful self-confrontation on long Buddhist retreats, that the perpetrators and their family were also victims, and that I am also a perpetrator and a bystander. I think it is easier for the public to demonise perpetrators than to try and connect with the suffering of those who are labelled ‘victims’. This is deeply unhealthy for our society. It makes me feel frustrated and sad that this is the case. It seems that we need to dig deeper, look within and learn something more about what it means to be human in response to human brutality and violence.

You have shared your story (and Lucy’s poetry) with inmates in male adult prisons to encourage them to experience victim empathy. How was that process for you?

I feel very privileged to have worked in 15 or so different prisons over the years (since 2001) in Restorative Justice settings. It has given me an opportunity to know that there is ‘that of God’ in everyone I have met and that sharing this story has brought healing in its wake. Meeting people who have committed serious crimes (rape, murder, sexual abuse) and listening to them respond to us with their own heart breaking stories has helped me to deepen my trust and to know that Lucy’s suffering is bringing something good into the world, despite the terrible loss and horror of it all. My work in prisons with the Forgiveness Project (www.theforgivenessproject.com) since 2005, with a 3 day programme called RESTORE, as a speaker and a facilitator has been even more amazing because it involves two speakers, one ‘victim’ and one ‘perpetrator’. The labels drop away and the prisoners begin to thaw and tell their own stories. Our work in a women’s prison with creative writing, as a follow up to RESTORE has led to a sharing of Lucy’s poems and a great harvest of poetry from the women. This has all helped with my healing enormously. It lives up to the meaning of Lucy’s name: light. I feel her gentle spirit is at work in the world.

You mention that your work as a homeopath has informed your work in male prisons. How so?

In my work as a homeopath for the last thirty years I have listened to many stories of traumatic loss and witnessed the serious dis-ease that can come from unresolved mental/emotional pain. As a homeopath I have learnt much about the path towards healing (moving from dis-ease towards becoming whole) with its unexpected twists and turns. I have had to apply this knowledge and experience to my own life and then to those I have encountered in prisons. I have tried to use words and the little woven bag that Lucy made for me when she was 8 years old as ‘remedies’ in the prisons and to listen as an ‘unprejudiced observer’. First I have had to face what needs to be healed within me. It seems to come back to developing a for-giving, compassionate heart: to face, accept and let go. I have known my own murderous rage and that it is easier to delude oneself and remain in denial than to begin to thaw. I work with ‘similar suffering’, growing into the truth that an old Chan master gave to me: just know that your suffering is helping to relieve the suffering of others. I feel grateful to all those I have worked with and met in prisons. This work generates cycles of compassion.

What would you like readers to take away from the book?

I hope that readers may learn more about the journey from the frozen silence towards the shining silence, from cruelty towards compassion, from harm to healing, and that carefully chosen words can initiate change. I hope that this book will help to confront and dissolve the roots of fear and prejudice that lie within and without, and that it will help to nourish and allow a more generous and loving world. I hope that people will come to know Lucy, my sister and feel something of the love that I feel for her, that seems to deepen.

For more information or to buy the book, please follow the link.

One thought