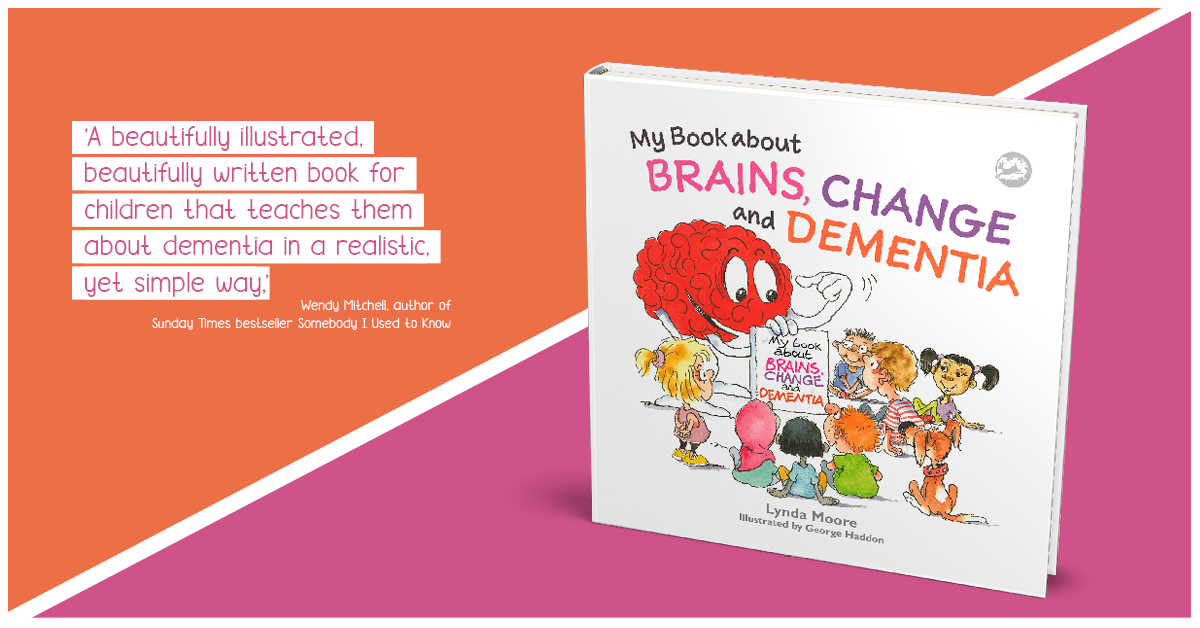

In this blog, Lynda Moore, the author of My Book about Brains, Change and Dementia introduces her new picture book about dementia, which encourages good communication with children when someone in the family has dementia.

In this blog, Lynda Moore, the author of My Book about Brains, Change and Dementia introduces her new picture book about dementia, which encourages good communication with children when someone in the family has dementia.

Answering questions like ‘What is dementia?’, ‘Why might parents, grandparents and teachers find it hard to talk about dementia with young children?’ Lynda outlines the benefits of having an open conversation with young children about the condition and how her new book can help.

If I were to ask you what dementia was, what would you reply? Many of us struggle to answer this question. We might be aware of the complexities of brain function and dementia and, for that reason, find it hard to give a concise response. It might be upsetting for us to discuss the realities of dementia when someone we love has the condition, or we might worry we will upset someone else if we talk about it. We might not know what dementia is because we have simply never found out. We might have also come to believe some of the common but misleading myths about dementia – “Dementia is something that only happens to older people”, or “People with dementia are just a bit forgetful”.

It is not surprising, then, that in the course of my counselling work with people with dementia and their families, I am often asked whether dementia should be explained to young children and how to go about having the conversation. This blog sets out to answer to those questions.

What is dementia?

Dementia is the term used to describe the symptoms of over a hundred known illnesses and conditions that cause progressive, incurable damage to the brain. Because the brain is critical to everything we think, feel and do, damage to the various parts of the brain can affect any aspect of our day-to-day life, such as our sensory perception (vision, hearing etc), mood, motor skills, memory and comprehension. It can impact our ability to plan, regulate emotion and behaviour, use language, empathise with others, judge distances, know where we are in time and space and so on.

Alzheimer’s disease is the most common cause of dementia. Other causes or types include vascular dementia, Lewy body disease, frontotemporal dementia, posterior cortical atrophy and alcohol related dementia. Some families use the name of the specific cause (e.g. Alzheimer’s disease) to refer to the disease process, while others prefer the term ‘dementia’.

How widespread is dementia and who gets it?

Dementia can happen to anyone, at any age. Although we are more likely to develop dementia as we age, young people can and do get dementia. Our clients at Dementia Australia include people diagnosed in their 50s, 40s and 30s.

There are currently around 50 million people living with dementia around the world (Prince et al, 2015). Many of them have children, grandchildren, nieces, nephews, neighbours and friends, so we can assume the lives of large numbers of pre-school and early primary school aged children are affected by the dementia of someone they know.

How does dementia affect the person who has it and their family?

Every person with dementia experiences a unique journey depending on the cause of their dementia, the way the condition progresses over time and the parts of the brain it affects, as well as on the person’s individual characteristics and circumstances. The cognitive impairment can be minimal in the beginning but, as the condition progresses, symptoms become more noticeable and varied and the person’s needs increase. This often puts pressure on family carers (Selwood et al, 2007) and creates a ripple effect through the wider family. Young children might be impacted directly, if they are close to or spend a lot of time with the person with dementia, or more indirectly. They might be confused, saddened, frightened or in some cases even endangered by the changes in the person with dementia. They are likely to sense the sadness and frustration of other family members, even if these remain unspoken. Some families experience financial strain, have to move house or are unable to maintain sporting, social or leisure activities due to the demands of caring. Some children experience stigma at school or in their community due to lack of understanding about dementia, increasing their sense of isolation.

There can be positives, too, for children in families living with dementia. These include an increased sense of closeness, trust, solidarity and collaboration within the family as they face the challenges dementia brings. There can also be opportunities for adaptation, increased self-awareness, empathy, personal growth and the development of new skills and resilience (Gelman & Rhames, 2016, pp 5,6).

Why should I talk to my child about dementia?

Our own practice experience, supported by a small study into the needs of children with a parent with younger onset dementia (Gelman & Rhames, 2016) and another into children with a parent with an acquired brain injury (Butera-Prinzi & Perlesz, 2004), finds that access to reliable information and opportunities to share feelings and talk things through when needed are key contributors to positive outcomes for children.

Just like the rest of us, young children need to be able to make sense of what they notice going on around them. For many children, the reality can be less frightening than the unknown. Acknowledging their fears, worries and questions sends a message that you are open to discussing difficult subjects with them and that, together, nothing is too big or scary to be faced. Talking directly with young children about dementia also allows you to reassure them that what is happening in the family is not their fault or their responsibility to fix.

How can I explain dementia to very young children?

Children of all ages, including very young children, impacted by dementia can be helped by having an understanding of:

- the healthy brain and what it does

- what dementia is and how it affects the brain

- how the child is affected by the changes and the emotions s/he might feel

- what can help children as they navigate life’s challenges

My Book about Brains, Change and Dementia is designed to help facilitate this conversation in an age appropriate, warm and sensitive way. It is relevant to every family living with dementia regardless of the child’s relationship to the person with dementia, the cause of dementia and the stage of dementia. Children have the capacity for great resilience and this book aims to help them tap into their own internal resources as well as the support of others around them.

BUY THIS TODAY AND GET 20% OFF – USE CODE BRAINS ON INTL.JKP.COM

Lynda Moore is a family counsellor with Dementia Australia, the peak body for people of all ages, living with all forms of dementia, their families and carers in Australia (https://www.dementia.org.au). She has a master’s degree in clinical family therapy and has worked for over 5 years counselling children impacted by dementia.

References:

Butera-Prinzi, F. & Perlesz, A. (2004). Children’s experience of living with a parent with a head injury. Brain Injury, 18(1), 83-101.

Gelman, C.R. & Rhames, K. (2016). In their own words: The experience and needs of children in younger-onset Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias families, Dementia 0(0)1-22, Sage, UK.

Prince, M., Wimo, A., Guerchet, M., Ali, G-C., Wu, Y-T. & Prina, M. (2015). World Alzheimer Report 2015: The Global Impact of Dementia. An analysis of prevalence, incidence, cost and trends, Alzheimer’s Disease International, London.

Selwood, A., Johnston, K., Katona, C., Lyketsos, C. & Livingston, G. (2007). Systematic review of the effect of psychological interventions on family caregivers of people with dementia. Journal of Affective Disorders, 101(1-3), 75-89.

If you liked this and would like to hear more about our new books, special offers and events don’t forget to join our mailing list! We can send information by email or post as you prefer. Follow us on Twitter and Facebook.