JKP author Marion Gordon-Flower discusses the motivations behind her new book.

There was a moment of epiphany that inspired this book through the recognition that, when working with archetypal approaches with people who had disabilities, there was an x-factor dynamic which came into play beyond that of other approaches. Working with the client group over a seven-year period, an informal body of research had formed which meant it was possible to compare approaches that offered an archetypal point of entry with those that did not. The archetypal approaches which were applied over the period were broad, including character cards, generic shapes, seasons and elements, and rituals. Case studies and scenarios have been presented across modalities of art, environmental sculpture, dance, drama and music, and in supervision. Both individual and group sessions have been reviewed and presented in a way that can be adapted for other client groups and contexts.

One of the most surprising encounters with the archetypal dynamic was reviewed in Chapter 4, Art Groups, Case Study: Ancient Civilizations (pp.50-59). When the art group arrived at ancient civilizations as a focus for their shared therapeutic journey, I initially had reservations that we might be about to embark on something akin to a school social studies project. I did not immediately make a connection with the archetypal underpinnings, which unfolded with deep significance through the course of the process. My response was to find ways of making the artistic journey relevant to their own personal stories. The process leaped into life as being archetypal when group members encountered Egyptian hieroglyphics and began incorporating the initials of their names into their creative process.

Using hieroglyphics led us into the understanding that images underlay the written language, and to write one’s own initials brought a sense of sacred connection with ancestors and doors opened into a realm where there were greater possibilities. We imagined the roles that people of the ancient worlds might have held and utility objects they might have used, which led to the creation of artefacts through found-object sculpture (with staff assistance). Through the artefacts created, stories then sprang forth about persons and archetypal traits, such as being princely, chiefly, champion-warrior and mother-goddess. The stories expressed stronger, more resourceful and resilient dimensions of artists themselves and could be related to their individual therapeutic challenges, and proved to be liberating, empowering and enhancing of self-esteem.

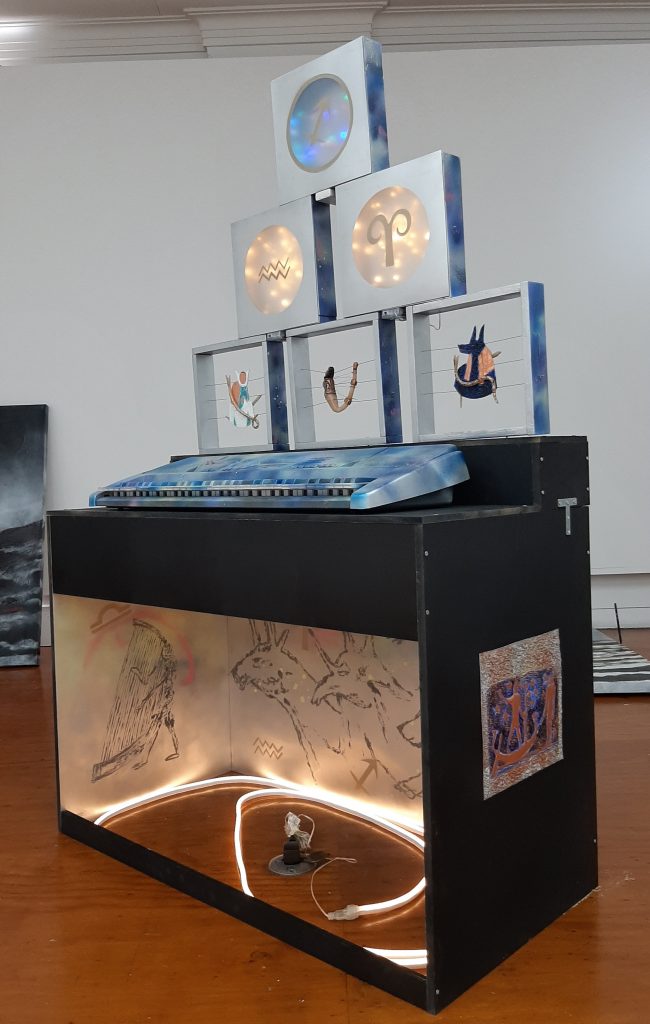

There has been cause to reflect further on these therapeutic journeys in response to a recent parallel. My partner, Rod Flower, and I have created a larger scale collaborative artwork incorporating found-objects sculpture for a group exhibition, ‘Symbolica, March 2020’ in our home city of Auckland, New Zealand. The inspiration for our concept arrived through our current employment at a mental health organisation which caters for diversity. Through our work, I had become more aware of significant cultural and religious events that involve the stars and the moon. Māori celebrate Matariki in which there is the appearance of a star constellation coupled with the new moon. Muslims around the world celebrate Eid which also arrives with the crescent moon. The Christmas story involves a star. In Pasific Island cultures, stories of navigation by the stars across waters are a significant dimension of culture. This undoubtedly influenced the decision to revisit the concept of astrology symbols from my art student days.

Our intentions were to combine our interests in art and music, and we initially focused on the notion of astrology being a past science which had recognised interconnectedness; that interplanetary dynamics influenced aspects of psyche and that theories extended into both colour hues and music. A playful toying with astrology symbols which were similar to alphabetic letters quickly led into ancient worlds and profound places. We slipped unexpectedly through the crevices into the wonder of archetypal dimensions and connected with ancient Egypt.

As with the art group, engagement with ancient worlds relied on photographic images from the internet, demonstrating further the power that visual representations can hold towards the unconscious mind. Egyptian symbolism arrived intuitively as being of significance, the rationale for which was discovered after their emergence in process, through asking the question, ‘What has this got to do with astrology?” Through facts seeking, we discovered foundations for both astrology and stringed-instruments music in ancient Egypt.

For me, the explorations led to a sense of expanded consciousness; an internal expansion and an awareness of vast parameters beyond our ourselves. Jung (1964) has stated that, “Our psyche is a part of nature, and its enigma is limitless. Thus we cannot define either the psyche or nature” (p23). He also highlighted that archetypal symbols reoccur through the unconscious mind in different cultures and times, providing an example of biblical symbols which were also found in ancient Egyptian artefacts (ibid). We reflected again on how music in itself is archetypal and is as much a form of elemental expression for the birds (and animals) as it for humans (Swallow in Gordon-Flower, p135).

We had not set out to make a therapeutic journey beyond the enjoyment of creative collaboration, yet I was ever aware that the creation of an artwork would hold therapeutic benefits. The engagement with astrology symbols led to reflections on memories of our parents; their strengths, our heritage. There was a consolidation related to personal identity and family connections, and the discovery of mutual interests in ancient Egyptian culture not previously expressed. We had become bigger people individually and in partnership through the course of the art-making.

Connections with cultural and ancestral roots, and the moon and stars, are significant in our mental health context and equally relevant when working with people who have disabilities. Our installation artwork tells its own story beyond any words that I could use in an attempt to describe it. It has the capacity to resonate with others on the level of the unconscious, archetypal and symbolic. Exhibiting was as important to us as it had been to the art group, who exhibited their artefacts to share their life journeys, and for their creations to be celebrated and pondered upon.

By Marion Gordon-Flower

Learn more and get your copy of the book, here.

References

Jung, C. (1964) Man and his Symbols. New York: Doubleday & Company Inc. Swallow, M. (2002) ‘The Brain – Its Music and Its Emotion: The Neurology of Trauma.’ In J.

Sutton (ed) Music, Music Therapy and Trauma: International Perspectives. London and Philadelphia: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.