Juliet Clare Bell is the author of more than ten children’s books including her latest ‘Ask First, Monkey!‘. Before writing for children, she was a developmental psychologist with a PhD from the University of Bristol. Bou Boundaries and consent are topics hugely important to her.

Ask First, Monkey! is a simple story about boundaries and consent, a subject that has been close to my heart for many years. In my twenties I was attacked walking home one night, and I feel very lucky to be alive. Mid-attack, two homeless men (to whom I am eternally grateful) walked nearby, realised something was going on, shouted at the attacker to stop, and one chased him whilst the other found a phone box and called the police. The attacker was caught that night and spent years in prison. Whilst my physical injuries were all superficial (in spite of a weapon), the psychological impact was much longer lasting. But it was more than twenty years before it even crossed my mind to write a picture book about boundaries and consent…

In June 2016, I read the victim impact statement after the Stanford sexual assault trial (where a popular, successful college student received only a six-month sentence for a serious sexual assault against an unconscious woman). I couldn’t get the thought of the perpetrator’s sense of entitlement out of my head. Nor could I forget the lack of empathy from the perpetrator and his supporters, or the way Chanel Miller (who has since waived her right to anonymity) had been disempowered by the brutal assault and the trial that followed (although she empowered herself spectacularly with her impact statement and her work since).

It was my turn to blog in our joint picture book group and I felt compelled to write about it even though the subject matter didn’t (initially, at least) feel like a natural fit for picture books. I scoured my bookshelves and looked online for more relevant stories, and wrote a blogpost on fictional picture books that encourage empathy in the child reader (as feelings of empathy would surely reduce feelings of entitlement?).

When I couldn’t find any picture books that looked at consent in this way, I decided to write one myself. What I really wanted was a story with a simple message, aimed particularly at children who hadn’t quite worked it out yet. I wanted children to understand that the thought:

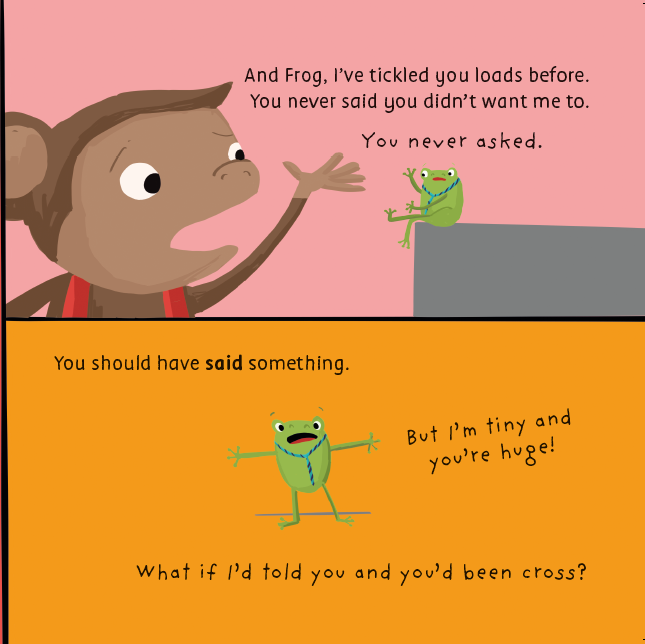

“This is fun for me” does not necessarily mean “this is fun for everyone” and that thinking “This is fun for me” does not entitle me to be able to do whatever I want, regardless of other people.

I wanted them to have a really straightforward understanding of:If I want to do something to you, or with you, I need to ask if you want me to.

If you don’t want me to, that’s fine and I won’t do it –and

I won’t make you feel bad for not

wanting me to do it.

It seemed such a simple message, and it frames consent as a life skill and not just related to sex at all (which has been a concern for some people when considering teaching consent to young children). I needed to find a child-friendly, fun way of getting it across, and things started coming together: I would write about tickling. I hated being tickled as a child. I was incredibly ticklish and felt completely out of control when someone tickled me. But plenty of children love it, so it would be perfect for discussions around what people like and how to find out what they like. And the people who tickled me weren’t horrible, but they were still thinking along the lines of “It’s fun for me therefore I will do it”.

It was an unchallenged habit. So I tried to write a book that would not humiliate or put off young children or the young character who hadn’t ‘got’ it yet, but that could help change inappropriate habits. We learn through the book with Monkey. And Monkey makes those mistakes but we see how he could have done them differently –and he ends up understanding, and putting that understanding into practice.

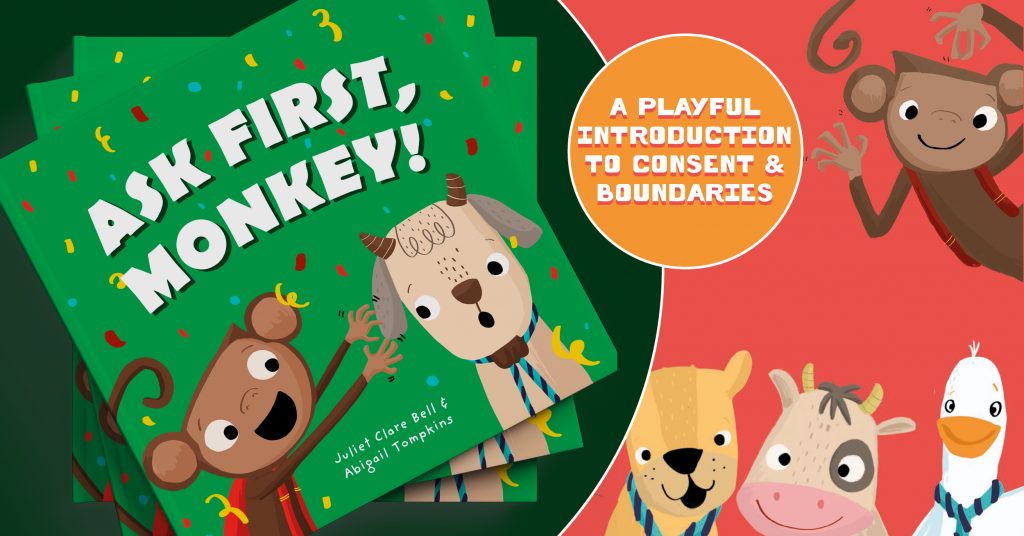

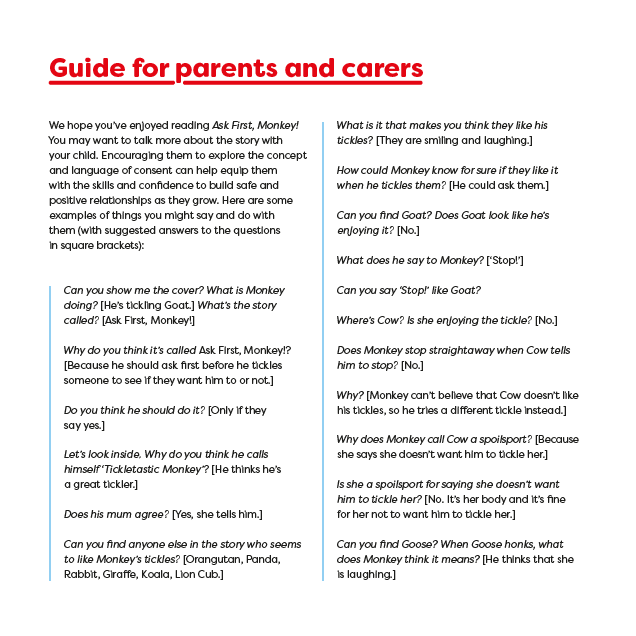

In order to make it as fun and non-threatening as possible for the reader, I’ve used animals as characters for the first time in my books, and Abigail Tompkins has illustrated in a bold, fun and colourful style. The book has direct speech only so we get a good sense of the characters’ voices and it’s easy to act out (especially useful in class settings, but fun at home, too), and I’ve tried to make it silly. It may be a story with a serious message but if it’s not fun to read, it’s unlikely that the message will stick as well. I wanted to touch on specific threads relating to consent: Goose says that her honking noise is not a laugh; Cow stands up for herself when she’s called a spoilsport for not wanting to be tickled; Lion Cub likes some kinds of tickles but not others, and Frog points out that he’s tiny compared to Monkey and wouldn’t have dared stand up to Monkey and tell him to stop.

These issues come up during the story in a non-threatening way so it’s easier to discuss them. And there are notes in the back of the book (and teaching resources on my websitefor parents/carers and teachers to facilitate discussion around the subject of boundaries and consent, choice and responsibility in a non-threatening age-appropriate way.

Almost all the women I’ve asked around my age (in their forties and fifties) have been sexually harassed and/or assaulted at some point in their lives. This suggests that there are huge numbers of people who have felt entitled to behave the way they want to towards someone else because it’s what they want, and because their wants override the need to check whether those wants are reciprocated. But if we think about discussing consent only in relation to sex, then we’ve left it way too late…

There are many skills involved in understanding and practising consent: understanding that people have different preferences for things; empathy; respect for others; self-worth and self-respect, which allow feelings of autonomy so that people can assert their preferences. We need for young children to adopt good habits in relation to consent –to understand and practise consent as a life skill.

Simple steps can help, like giving children choices from a young age (who would like an apple, and who would like a banana?) so that they are used to the idea of preference, and allowing them to act on those choices (great, you can have a banana, you can have an apple, etc.) so they understand that their opinion counts. Once children understand that different people have different likes and dislikes, it makes more sense to ask first (–and to act on the answer). And we have a responsibility as parents, too. If we want our children to understand body autonomy, and expect them to ask first, we should be modelling that: we need to allow them to choose if they’d like us (or their granny, or their uncle) to hug, or kiss or tickle them. If young children see other people behaving this way towards them, it will be easier to for them to get into the habit of asking before doing something to someone else (tickling, hugging, touching someone’s hair, borrowing someone’s things, etc.). And when they reach their teenage years and beyond, it will be normal to ask permission for anything, and if the other person says no, they are less likely to feel entitled to do it anyway.

The Me Too and Time’s Up movements have helped alter the landscape since I first read Chanel Miller’s victim impact statement and felt compelled to write Ask First, Monkey! Conversations and teaching around consent are considered much more mainstream and there are new books coming out for toddlers, young children, teens and adults. The updated Relationships Education (Department for Education, 2020) means that children in England and Wales will be learning about boundaries and consent from a very early age. I’m not naïve enough to think that no one who learns about consent from a young age would abuse their power at some point, but I do think that using simple, straightforward messages around consent starting with young children, will mean that fewer people grow up with the dangerous sense of entitlement: “This is what I want (regardless of the other person’s wants) therefore I will do it”.

Excellent article, Clare, and beautifully written, as always.

As with all the best children’s literature, your book is as relevant to adults as it is to children.

I’m in awe of your talent, your honesty and your bravery.

Long may you continue to write!

Thanks, Claire. You’ve said it all.

This is such an important topic, Clare, and the earlier people learn about consent and boundaries, the better everyone will be! I’m looking forward to buying this for the kids in my life. I wish this book had been written when I was a kid, but I’m glad you’ve done it now.