10 things I have learned about coping with serious illness

Who doesn’t love a good thriller? A dramatic opening chapter, lots of twists and turns along the way and then a thoroughly satisfying conclusion – perhaps with one last surprise on the final page. If someone in your family suddenly falls seriously ill, the feeling that you are in a film, a book, or having some sort of weird dream is incredibly common. (I think many of us had the same surreal sense of “surely this can’t be real” at the start of the pandemic.) But unlike fiction, real life does not have a neat beginning, middle and end. When coping with serious illness there is no arc, no climax, no resolution and you never know which chapter of the story you have reached.

When my husband Alan was struck down out of the blue by the terrible brain inflammation encephalitis and then spent the best part of a year in hospital, one of the things I found hardest to accept was that my family and I were going to have to learn to live with uncertainty. As an organised person who likes a plan, this was hard enough, but as a parent who wants to make things alright for their children, at times this was almost impossible to come to terms with. Here are ten things I have learned about coping with the many insecurities and doubts that come with serious illness.

- Doctors are not gods, and they do not have all the answers.

They can only tell you what they are able to diagnose, and they don’t like guessing. Sometimes this may mean that they can only tell you for sure what your illness isn’t, but not what it is. - Do not use Google to find things out about illnesses.

Because of its algorithm, the popular answers will come up first, and these may well be wrong. They are also likely to terrify you! It is highly unlikely that your “research” will discover something that scientists and doctors don’t know about. Use a more curated form of information, such as a charity website, the NHS or a book. - If you or someone you love is suddenly taken ill, the emotional shock can cause post-traumatic stress.

This is your body’s normal reaction to an abnormal event. You may feel intense fear, anger, numbness, vulnerability, or sadness. Things that may help are rest, routine, talking about it and time. - When talking to children, it is OK to say you don’t know.

But focus on what you can be sure of rather than what you can’t. Saying something like “I don’t know if dad will be out of hospital for your birthday, but we are going to make a birthday cake this afternoon together” is better than saying “let’s wait and see.” - Cultivate a realistic but optimistic mindset.

You cannot alter the physical course of an illness, and I am certainly not saying that you can will yourself well, but you CAN alter how you feel about it. You do have control of your own mind. - There is a Chinese proverb that says, “It is better to light a single candle than to curse the darkness” and I think this is an excellent motto to keep in mind.

Doing something – however small – rather than doing nothing is a good idea. Getting on top of things you CAN control will often help you feel better about the things you can’t. Small positive actions like completing household chores or sorting out paperwork can make you feel less helpless and vulnerable. - Finding out exactly how machines like scanners, or hospital tests work, can be very reassuring.

This can be an especially useful tactic with children. Sticking to the practicalities and the certainties of science can be much more supportive for them than woolly words of comfort. - Studies have shown that the families who come out of illness best are those who “struggle well” – learning from adversity together.

If you can help your family to become more resilient, this will undoubtedly serve all of you well in the future. - Use humour.

Anyone who has friends who are medical students will know they have a, shall we say, “robust” sense of humour. It is OK to find things funny even in the darkest times. Laughing makes you feel better, and it can be a brilliant survival mechanism. Alan’s brain injury meant that he often got the words wrong for everyday things, or believed he was in all sorts of weird and wonderful places rather than a hospital bed. This was sometimes frightening – but it was also hilarious. - It IS possible to live with doubt.

Will the medicines work? The doctors and the scientists hope so, but they can’t be sure. Do prayers work? No one knows. If you had done things differently, would the outcomes have been different? Possibly. Call it fate or call it chance, accepting that uncertainty is part of life, can bring you peace. Endlessly worrying will not.

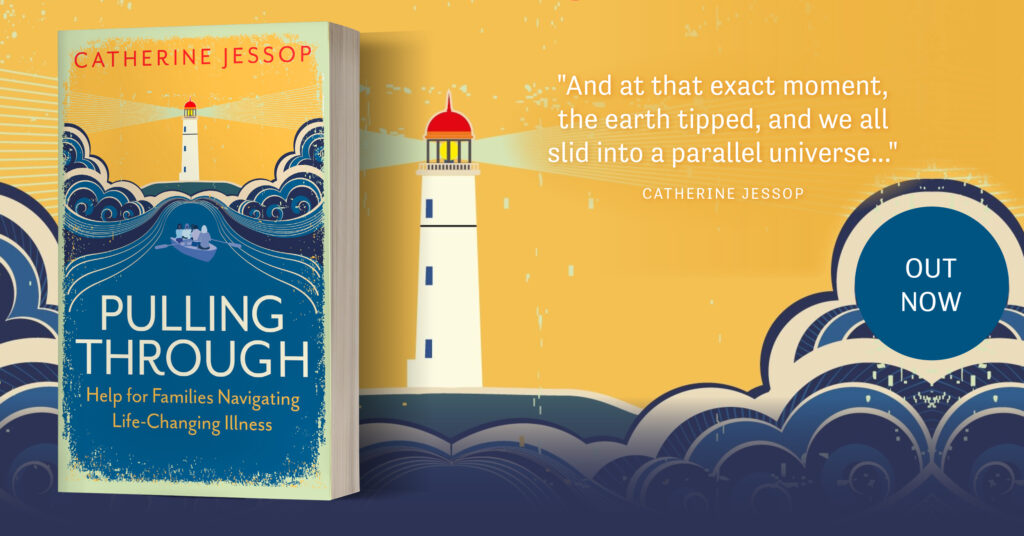

The book I have written about my family’s experiences, Pulling Through: Help for Families Navigating Life-Changing Illness certainly does have a highly dramatic opening chapter, and readers have said it is a gripping tale! And in many ways, writing it has helped me knot the threads of our story into a kind of ending. But it has also helped me to see that no one knows what will happen next in life – and that’s OK.

I hope that by sharing our experiences, others will gain something from everything I have learnt; how to decipher the impenetrable language of doctors, how to navigate the complexities of hospitals and the NHS, how to talk to your friends and children about serious illness, how you can use nature, music and humour to help you and most importantly, how to look after your own mental health while taking care of those you love.

Paradoxically, although my husband’s illness means that our future is far less organised and planned out than it was four years ago; I feel that I am much better equipped to face whatever happens next. And I hope that anyone who reads my book will also be better prepared for any of the curveball challenges that serious illness may throw at them.

Delighted to see this book! I haven’t read it yet but I like the above. Personal accounts can be very helpful and make good reading.

Julia Segal

Author: The Trouble with Illness. How Illness and Disability Affects Relationships. Jessica Kingsley, London, UK