Help Your Dyspraxic Child Find Their ‘Eureka Moments’

Read this article with 5 helpful tips on helping your dyspraxic child find their strengths, written by Alison Patrick, author of We Are The Dyspraxia Champions.

My mum knew I was different from the moment I began bottom shuffling instead of crawling and then didn’t walk until I was nearly two. I knew I was different as soon as I noticed I couldn’t do the stuff everyone else was doing so easily: catching a ball, running fast, riding a bike. But I didn’t actually know about dyspraxia until I was in my 40s and I didn’t know for sure that I had dyspraxia until it was diagnosed by a kind neurologist when I was a whopping 53 years old!

My dyspraxia has always made physical tasks, even the most basic ones, a bit of a challenge. But it’s not all bad, and I wouldn’t be without dyspraxia in my life because I like the way my dyspraxic mind thinks.

Here’s some of the Eureka moments that can help a child to vibe with their dyspraxia.

1. Reading

I didn’t read until I was 8 years old, then one day I could read all the words. One moment I couldn’t read; the next minute I could. I shouted, ‘I CAN READ!’ and it was literally the best Eureka moment I have ever had.

Why did I suddenly learn to read well so late? I think it’s because, for a dyspraxic child, visual processing may improve as vestibular skills strengthen. I also think its because we’re slower to learn new things

The good news: once reading is secure, there can be a strong aptitude for reading, forever.

2. Riding a bike

That Eureka moment when a dyspraxic child suddenly rides a bike tells us a lot about dyspraxia. Despite any difficulty and hardship experienced while learning, a dyspraxic child will ride a bicycle just as well as anyone else, it will just take longer and need more practice. Riding a bike will help with the physical side of dyspraxia because it can improve bi-lateral skill, balance and coordination.

3. Finding the Right Activity

Are dyspraxics born with an aversion to sport? I don’t think so. Children love to be active but it can be demoralising to be less coordinated than your peers. Sport doesn’t have to be about catching, kicking, throwing or speed. And there can be a Eureka moment when suddenly there’s an activity which is actually doable and fun

Examples of dyspraxic sports:

- Swimming (which is good for proprioception too).

- Karate (which can help with balance and coordination.)

- Dancing (which can also help with coordination and balance).

It’s not about forcing; it’s about finding.

And, there’s one other activity that could be very good for dyspraxia. Various researchers have shown that video game skills are associated with improved hand-eye coordination, visual-spatial memory and attention.

4. A New Pen

Dyspraxia and handwriting do not go well together. So, for a child who is struggling to find a comfortable grip for writing and finding it hard to form letters or write legibly, being given a dyspraxia pen can result in another Eureka moment. Imagine the surprise and elation when a simple change of pen makes something that was a trial, a painfree and legible pleasure.

5. Getting Insoles

It can be very tough for a dyspraxic child with low muscle tone and flat feet. Imagine the Eureka moment when life is instantly transformed by a pair of insoles. That sudden transformation from a world where it’s painful to walk and practically impossible to run; to a world where walking is actually comfortable and you can keep up with your peers when you are running. The one thing no dyspraxic (whatever their age) will ever forget (or lose) is their insoles.

6. Getting top marks

I don’t know whether this is a Eureka moment or more of a Eurekaargh moment, but unpredictable scores can be a highly predictable aspect of dyspraxia at school. You could have the euphoria of getting 20/20 for mental arithmetic or a spelling test one week. And then the sorrow of getting 4/20 exactly one week later. So, inconsistent performance at school can be a mixed blessing for dyspraxics in the classroom. This can confuse everyone: teachers, parents and the dyspraxic themselves. But it’s worth remembering that those 20/20 scores show a lot of potential and the erratic scores show that there might be underlying difficulties requiring some reinforcement and support.

If we know that performance can be variable, we can celebrate the good scores whilst not giving ourselves a hard time over the poor scores.

The bottom line: those ‘I Can’ moments can make a big difference for a dyspraxic child, and they’ll remember those Eureka moments forever.

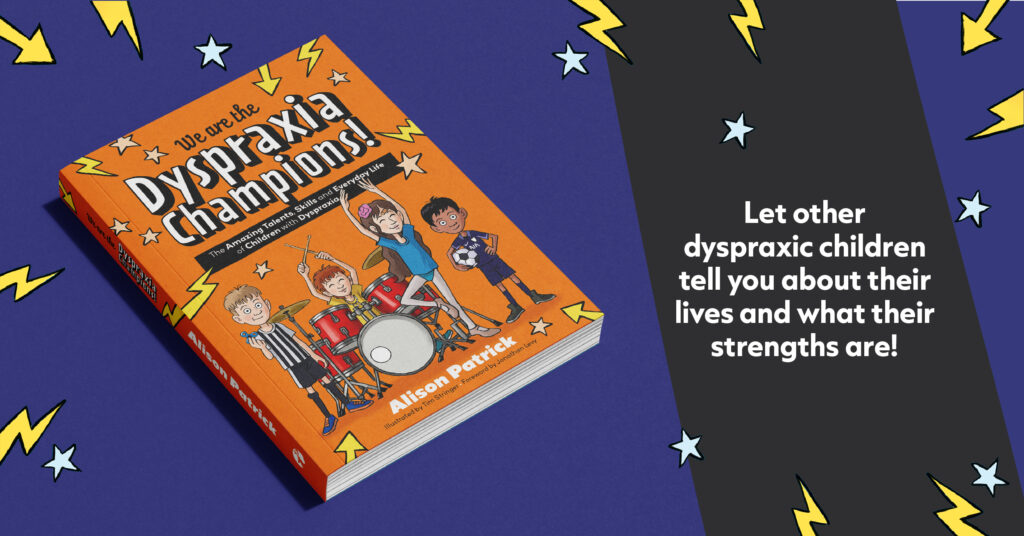

For more about being a dyspraxic child, read We are the Dyspraxia Champions by Alison Patrick.