Why Our Queer Pride Must Be Intersectional

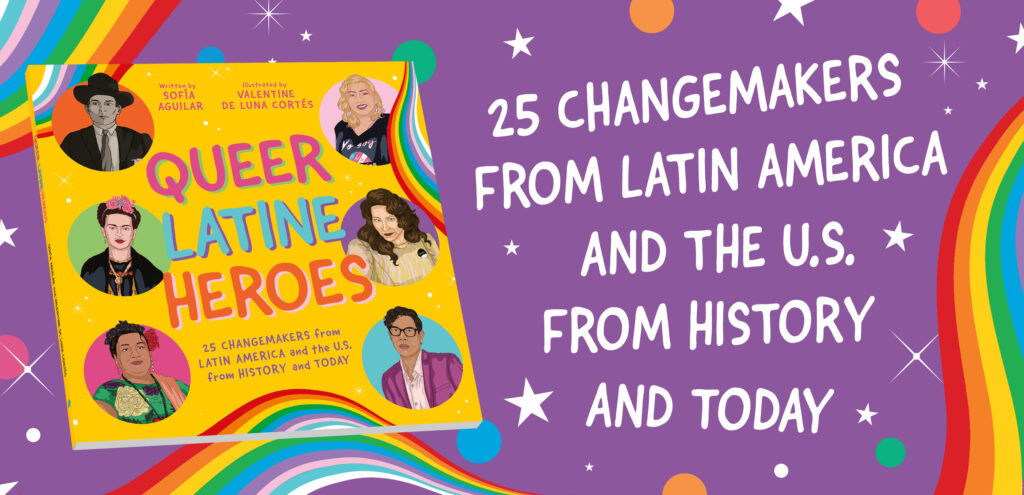

By Sofía Aguilar. Find her book, Queer Latine Heroes here.

Whitewashing is all around us, whether we are aware of it or not.

It’s not just in movies, TV shows, and other media where white actors are cast in roles meant for actors of color, however explicit or implicit their identify is communicated in the source material. It’s everywhere.

In the way we talk about the population demographics of a place, how we move through the world and compare ourselves to others, how we choose what books to read. Even how we celebrate the communities we come from.

The Pitfalls of Pride Month

During celebratory awareness months like Pride Month, it’s not unusual to see social media posts or articles online uplifting a carousel of queer icons–and notice that they are overwhelmingly white. They can represent a diverse array of fields and occupations, from political leaders to activists and organizers to influencers, all while maintaining this facade of whiteness as the majority. Which means people of color, much like in real life, are tokenized, othered, and seen as a rare exception.

Granted, it isn’t always intentional. I believe whitewashing works in such a way that we aren’t even aware we’re doing it most of the time because the perception of whiteness as the standard has become so normalized. It’s also true that white queer folks have undoubtedly contributed to the LGBTQIA+ movement and efforts for queer rights, and, without question, deserve their praise and attention.

However, when we prioritize whiteness over every other identity, queer people of color end up ignored and left out of LGBTQIA+ celebrations, literature, and studies. Not only does the community become yet another space where they do not belong or feel welcomed, but they also don’t get credit or recognition for their labor. Advocacy and activism is often laborious and thankless, if not dangerous, and we all deserve to be recognized for the impact we’ve made on culture, society, and the world.

And if I’m being honest, the excuse for such exclusionary behavior has long stopped becoming relevant or meaningfulness, especially in today’s culture that has a rising awareness of political and social issues. Our internal biases, regardless of intent, ultimately help no one and harm everyone.

Of course, representation may not be the end-all, be-all equality and liberation. However, it can be an effective first step toward important conversations and wider awareness of our unique needs, struggles, and values.

In Latin America

It may surprise some of you who aren’t part of the Latine community and know our history well, but Latin America is no stranger to this either. White supremacy, anti-blackness, and anti-indigneity are baked into the fabric of our societies, cultures, and languages throughout the region. Much like in the U.S., it can often appear normal or harmless, like an all-white panel of journalists reporting the daily news. Then it manifests itself into casual racist epithets spewed in government meetings, hate crimes, and Indigenous communities being the last to receive government aid in disasters (if ever).

That violence carries over into the LGBTQIA+ community as well. There are a dozen different slang words in Spanish for “gay” and “queer,” most of them with deragatory or negative connotations. Queer folks across race, gender and sexuality are more likely than heterosexual people to be murdered or experience domestic violence. As of 2024, the average life expectancy of a trans woman in Latin America is no more than 35 years.

It’s a humanitarian disaster that not many people know about, including in the LGBTQIA+ community in the U.S. Why? Because they’re not always white and located in the Global South.

So not only does this cause people like queer, Indigenous, and Afro-Puerto Rican writer William Brandon Lacy Campos to go his whole lifetime without being credited for how he raised awareness of HIV/AIDS in the queer Latine community; but it also puts our very lives in danger because we are seen as less human than everyone else.

It means our very lives are at stake.

Not One Story, But Many

I love being Chicana. I love being queer. I love being femme. All of these identities are part of me, intertwined and carrying long cultural histories. When they intersect, they tell a complicated but ultimately more interesting story about who I am, where I come from, and where my family calls home.

That’s why I decided to write Queer Latine Heroes: 25 Changemakers from Latin America and the U.S. from History and Today. After writing about these issues for years for various outlets and journals, as well as studying them in school, I realized that no one had yet compiled the stories of notable queer Latines into a book, much less for kids.

Even within our own community, it’s not a surprise to see the same four or five Latines highlighted in round-ups for Pride Month in June, or mentioned as an aside during Latinx Heritage Month in September. For the first time, I wanted those of us with this unique intersection of culture, sexuality, and gender to be the center without apology or shame. For us to be seen and loved completely for who we are.

When I began this project, there were people I knew had to be included, like Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz and Frida Kahlo. But as I researched, I learned new names that I’d never heard of before, such as Lukas Avendaño and Raffi Freedman-Gurspan, and felt a sort of indignation, even anger, that they had been kept from me for years.

Even now, I bring certain folks up in conversation with potential readers, and their blank faces, that lack of recognition, has become familiar to me as much as it’s ignited a promise to keep their names and stories alive, to praise them while they are still here with us.

I want Latine children–and readers of all ages–to read this book and get excited to see themselves represented, whether it’s a person’s gender identity or the country they come from. I want them to know they are seen, that they are valued and worthy of praise. They should feel empowered to be who they are.

In the book, there is a one to two-paragraph biography of each hero, accompanied by an illustration and fun fact about their life. At the back, there is also a glossary and a list of sources for families and researchers to conduct their own investigations into their stories and learn more. I’m proud to see my book as a first step for people to fall deeply in love with this community and perhaps even discover something about themselves along the way.

It’s never easy being the first to do something. And frankly, I wish it hadn’t taken this long. But I’m proud to finally have this book out in the world and to give back to my communities who have given me so much love, support, and visibility over the years.

This book is no longer just mine anymore, but a gift that now belongs to all of us. Pa’lante!

Sofía Aguilar (she/they) is a Chicana writer, editor, and library professional living in Los Angeles. Her work has appeared in the L.A. Times, Refinery29 Somos, and New Orleans Review, among other publications. She is also the co-founder and editor-in-chief of Mag 20/20, a multi-media magazine spotlighting creatives in their 20s; the co-founder of Tenderheart Collective, an online poetry house led by and for BIPOC womxn writers and the creator of Creativity Café, an IG Live series in conversation with writers of all backgrounds. For her groundbreaking research in queer Latine history, she has received honors including the Spencer Barnett Memorial Prize for Excellence in Latin American and Latinx Studies.