Chris Mitchell author of the new book Mindful Living with Asperger’s Syndrome reflects on how mindfulness practices can help individuals embrace living in the current moment.

Chris Mitchell author of the new book Mindful Living with Asperger’s Syndrome reflects on how mindfulness practices can help individuals embrace living in the current moment.

An aspect of living with Asperger’s Syndrome that I feel I have gradually begun to notice and appreciate more through mindfulness practice, (that the effects of anxiety presented by the condition can easily hide), is that the present is the only time that we have to be alive, and to make the best of who we are. Many mindfulness exercises emphasise moment-to-moment awareness and being present with each moment as it unfolds. The more we live in each moment as it unfolds, the more we can begin to open up to our life being a continuum, where each moment, good or bad, pleasant or difficult, is absorbed into one continual moment.

Such individual moments and phases throughout one’s life rarely occur in isolation, as the many individual moments and phases often have to happen, not just for the next moment to happen, but for one’s life to unfold as a continual now. Those diagnosed with Asperger’s Syndrome later in life, including myself, will likely appreciate that certain events or periods in their life, such as depression or low self-esteem, had to happen for them to seek and obtain a diagnosis. Such phases can almost feel like we are mentally suffocating to the point where we want to eliminate them, b ut instead, what if we were to change our relationship with them?

ut instead, what if we were to change our relationship with them?

Personally, my two favourite aspects of mindfulness practice are its simplicity and its flexibility. The simplicity makes it accessible to just about anyone who seeks the practice while the flexibility aspect allows mindfulness to be weaved into one’s day-to-day activities and experiences. Mindfulness practitioner Jon Kabat-Zinn suggests that every moment of your life is an opportunity to practice mindfulness if it is important to you, including through difficult periods such as depression. Sometimes though, it helps to come out of our comfort zone to both see and experience the value of living in the moment of now.

In this context, by ‘somewhere outside our comfort zone’, I refer to somewhere that it not the norm for us, away from conveniences we are used to and expectations we may have of life. An eye-opener for me was Kulusuk, a remote town located on the east coast of Greenland. Here living standards and the outlook and expectations of life are very different to what they are for many of us in the developed world. When visiting such a place, as well as appreciating what you have back at home, sometimes one also revisits lost values.

Floating pieces of ice in the bay around Kulusuk that have broken off outlet glaciers from the ice sheet that covers much of interior Greenland are one of the first signs the visitor sees of a continual now in action; interlinked existence of the floating pieces of ice as part of the ice sheet, breaking off and eventually melting, in the broad spectrum of time, many moments absorbed into one. Harsh conditions for many Native Greenlanders (Inuit), especially during winter, can mean that time is short. Regarding life expectancy, many don’t expect to live much beyond 50. To make the most of their lives, many Inuit are culturally accustomed to living in the moment, to the extent that their entire life almost becomes a continual moment.

It is not to say that contemporary Greenland is without its problems, as, sadly, it also currently has a high suicide rate. However, in the developed world, ways of thinking that we have become accustomed to (or sometimes lost in) mean that we may over-focus on where would like to be in the next five years or what we will do when we are there rather than be with the present. Obsessive compulsive tendencies present with Asperger’s Syndrome can see one becoming attached to such thoughts that they become controlled by it, which can also lead to depression when one doesn’t see such life expectations come to fruition. Depression can then absorb one from how it actually is as well as how they are within themselves.

This is where changing our relationship with feelings of depression and low self-esteem through application of mindfulness comes in. Rather than be constrained or frustrated by persistent feelings, we can work with them, helping us to come into the present more. We can learn more about who we are, enabling us to understand ourselves better, our emotions, personal qualities and how they are perhaps affected by Asperger’s Syndrome, as well as being aware of weaknesses we feel we may have. Strengths and qualities that  Asperger’s Syndrome can present can also aid bringing mindfulness to each moment of life’s continual moment, including bringing attention to detail of the present moment.

Asperger’s Syndrome can present can also aid bringing mindfulness to each moment of life’s continual moment, including bringing attention to detail of the present moment.

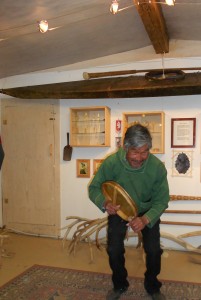

Once we understand ourselves in this way, it helps us to become more realistic about what we can expect from life by accepting and appreciating the continual moment of the life we have in the present, where we can make the most of ourselves as people with Asperger’s Syndrome. As an Inuit drum dancer performs an ode to nature in Kulusuk, he reminds us we need not be afraid of what nature throws at us, but to simply be aware of the time we have to live.

Chris Mitchell is the author of new book Mindful Living with Asperger’s Syndrome and Asperger’s Syndrome and Mindfulness both published by Jessica Kingsley Publishers.