Featuring suicide in a picture book may sound like an unlikely combination to some people, which is why we’ve asked Emmi Smid, author of Luna’s Red Hat to explain what motivated her to write and illustrate Luna’s story.

That art is a necessity to society’s well-being and structure is, in my humble opinion, a fact; creative people have the ability to shine a light on important matters from different perspectives. Through their words, visuals and sounds, these products of creativity encourage us to ‘think outside the box’, touch people’s hearts and bring people closer together.

My background originates in Fine Art. With my above-mentioned image of “The Artist” in mind, I struggled to find the ‘use’ for my own art within our modern day society. What do I have to offer that could potentially add something positive to how we think about and deal with current social matters?

During my time at the University of Brighton, where I read for a Masters degree called Sequential Design/Illustration, I started revaluing the importance of the picture book, and how a balanced ‘marriage’ between words and pictures can teach not only children, but also adults, simple but profound lessons in life. So, I started by revisiting my collection of picture books that handle the topic of death: Michael Rosen’s Sad Book, Wolf Erlbruch’s Duck, Death and the Tulip, Oliver Jeffers’ The Heart and the Bottle, among others. Then the penny dropped. As beautiful and heartfelt as each of these picture books were, none of them touched upon the topic of loss through suicide. I noticed this because I have lost loved ones to suicide. I was 16 when my friend Bram committed suicide. We were the same age, and we were raised on the same street. We went to primary school together, and after that to secondary school. As far as I knew Bram was always going to be a part of my life, until he wasn’t. His sudden death came as a shock to all of us – Bram’s family first of all, my family, our mutual friends and their families, our teachers, the school, there was a real ripple effect.

In the spring of 2009, when I was 21 and had moved from my home country the Netherlands to England to study Fine Art at University College Falmouth, my aunt Judith committed suicide. She left behind her two daughters, Merel and Silke, aged 14 and 10 at the time. Being away from home, I felt rather disconnected from my family. I was concerned about my cousins – with all of us struggling to grasp the notion of suicide and getting our lives back on track, how were my cousins going to deal with this at their age? I felt powerless and useless.

Fast-forward to January 2014, and there I was discussing the idea of designing a picture book about dealing with loss through suicide with one of my tutors at the University of Brighton. I was very passionate about the idea but the fact that there weren’t many books about the topic made me doubt myself. “If you are not sure, then maybe you should start by finding out why there aren’t many children’s books about suicide?” my tutor suggested. So I sat down and came up with a number of reasons why: the notion of death is difficult enough for children, let alone dying by apparent ‘choice’; we live in a society where children are wrapped up in cotton wool and are protected from real life for as long as possible; Suicide is still a social taboo.

None of these reasons felt very satisfying – in fact, the more I thought about it, the stronger the urge became to confront and perhaps even tackle those reasons. Children are as clever as adults, with the difference that they lack life experience. The only way for adults to help children gain life experience is to provide them with the tools to deal with life, as and when it happens. Social taboos are created and perpetuated the same way: it all boils down to our own lack of tools to be able to empathise rather than judge, communicate rather than ignore, and confront rather than beat around the bush.

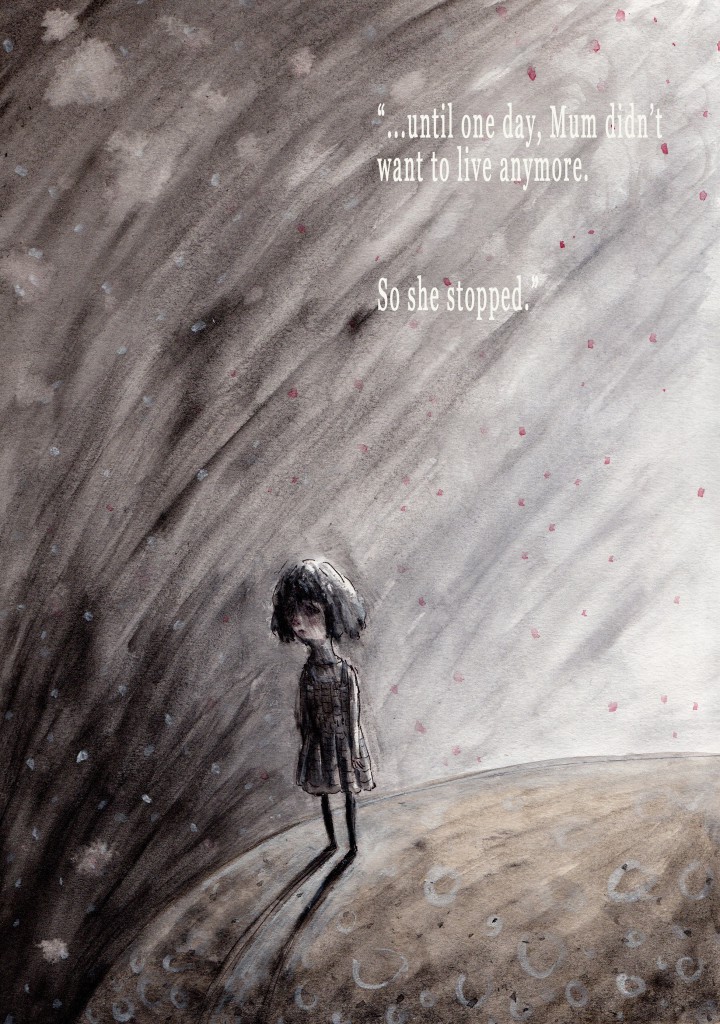

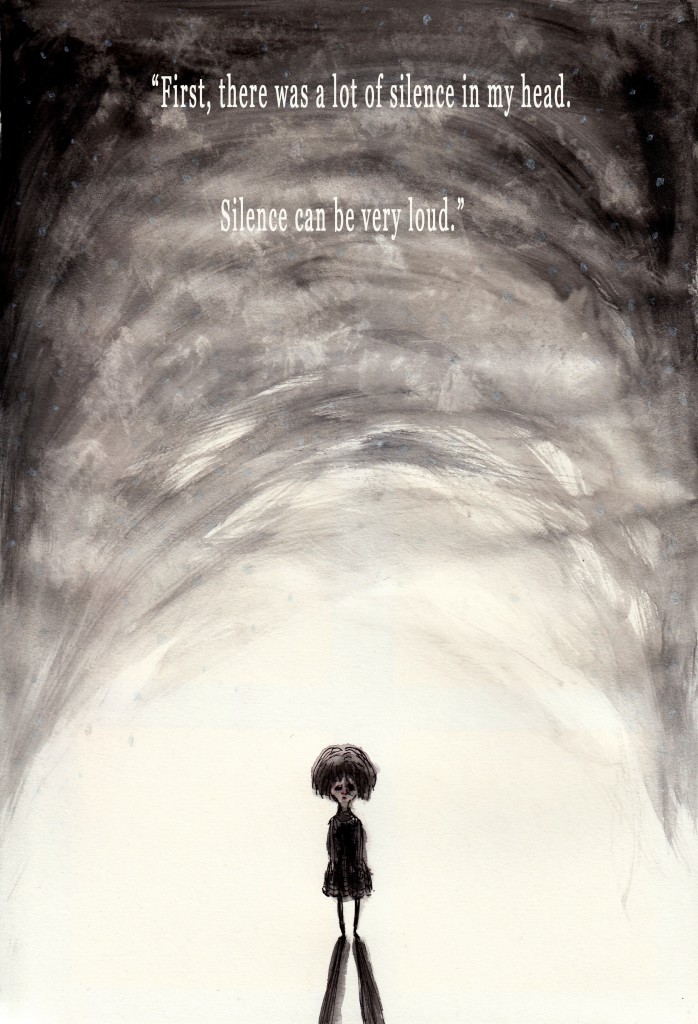

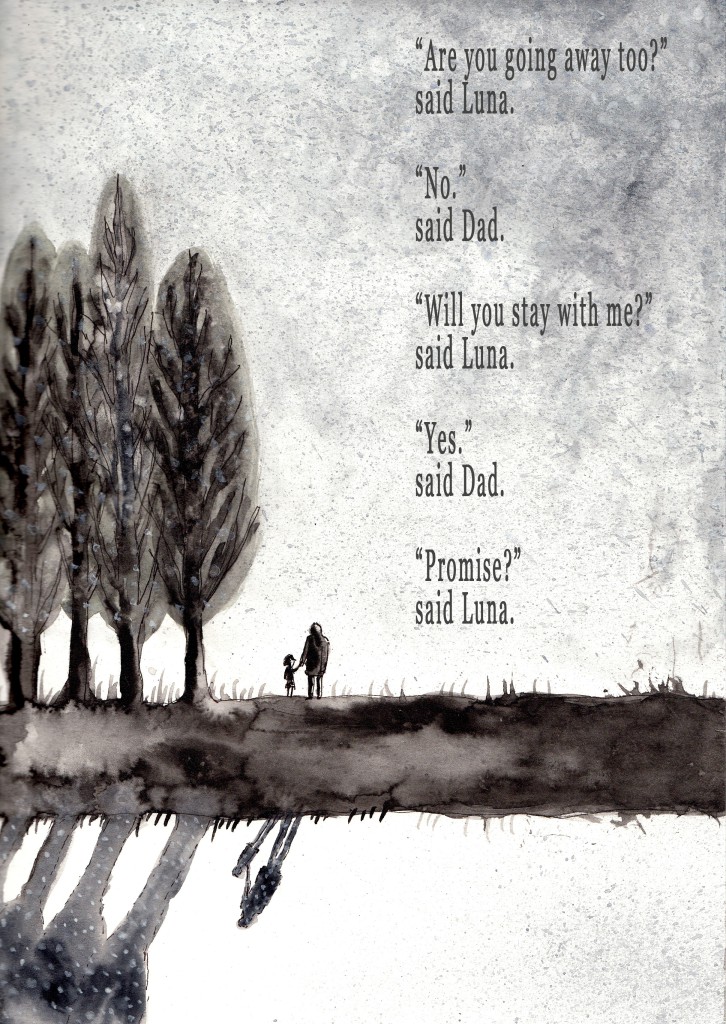

Unfortunately, people commit suicide. I have felt isolated and lonely when trying to deal with overcoming the loss of my friend and my aunt, and I have seen the effects it has had on my family and friends. If we adults are struggling, then how will young children deal with such a loss? Determined and on a mission, I created the first series of sketches telling Luna’s story:

I posted the sketches on my blog and asked people for feedback. The reply of Alexis Deacon (writer and illustrator of picture books such as Beegu) made me take a step back and reconsider my approach: “You might try offsetting the sadness with moments of humour or just exploring different kinds of sadness. After all, the message is an important one and you are more likely to reach a wider audience if you don’t club people round the head with it!”

Considering the sensitivity of the topic, I also decided to get feedback from specialists in the field. During my research I read the book Couldn’t You Stay for Me? by Dutch bereavement specialist Dr Riet Fiddelaers-Jaspers and contacted her. Riet has been an immense help ever since, providing me with feedback regarding different stages of grief and sharing her expertise with me. She also agreed to write the ‘Guide for Parents’, her contribution in the back of Luna’s Red Hat, which is designed to help parents, carers, teachers and professionals to support and communicate with children who have lost a loved one through suicide.

In search for feedback from parents who have been through similar situations, I contacted Belgian bereavement institution Werkgroep Verder. They agreed to share my manuscript with some of their clients, and I received some very useful and eye-opening replies. The one that got to me most was feedback regarding one of my illustrations. I wanted to show Luna being overwhelmed by her own anger, through drawing a big metaphorical red wave of anger behind her. A parent rightfully pointed out that one never knows whether the child was exposed to the incident, and that “splashes of red liquid” may cause further pain. I instantly decided to make the wave blue instead.

Designing Luna’s Red Hat has been a tough but blessed learning curve, personally as well as professionally. There are many more insights into the process that I could show you, but the main insight I would like to share with you, is that we can learn to embrace our losses together, however heartbreaking they may be. I wasn’t able to physically be there for my cousins Merel and Silke when they lost their mother, but I dedicate this book to them. If Luna’s Red Hat could provide parents and their children with a new perspective or hope in even the slightest way possible, then that would mean the world to me.

Emmi Smid is a children’s book author and illustrator. She was born in the Netherlands but currently lives and works in Brighton, UK. Learn more about Luna’s Red Hat here.

Thank you so much for sharing your personal experience in creating this beautiful book.