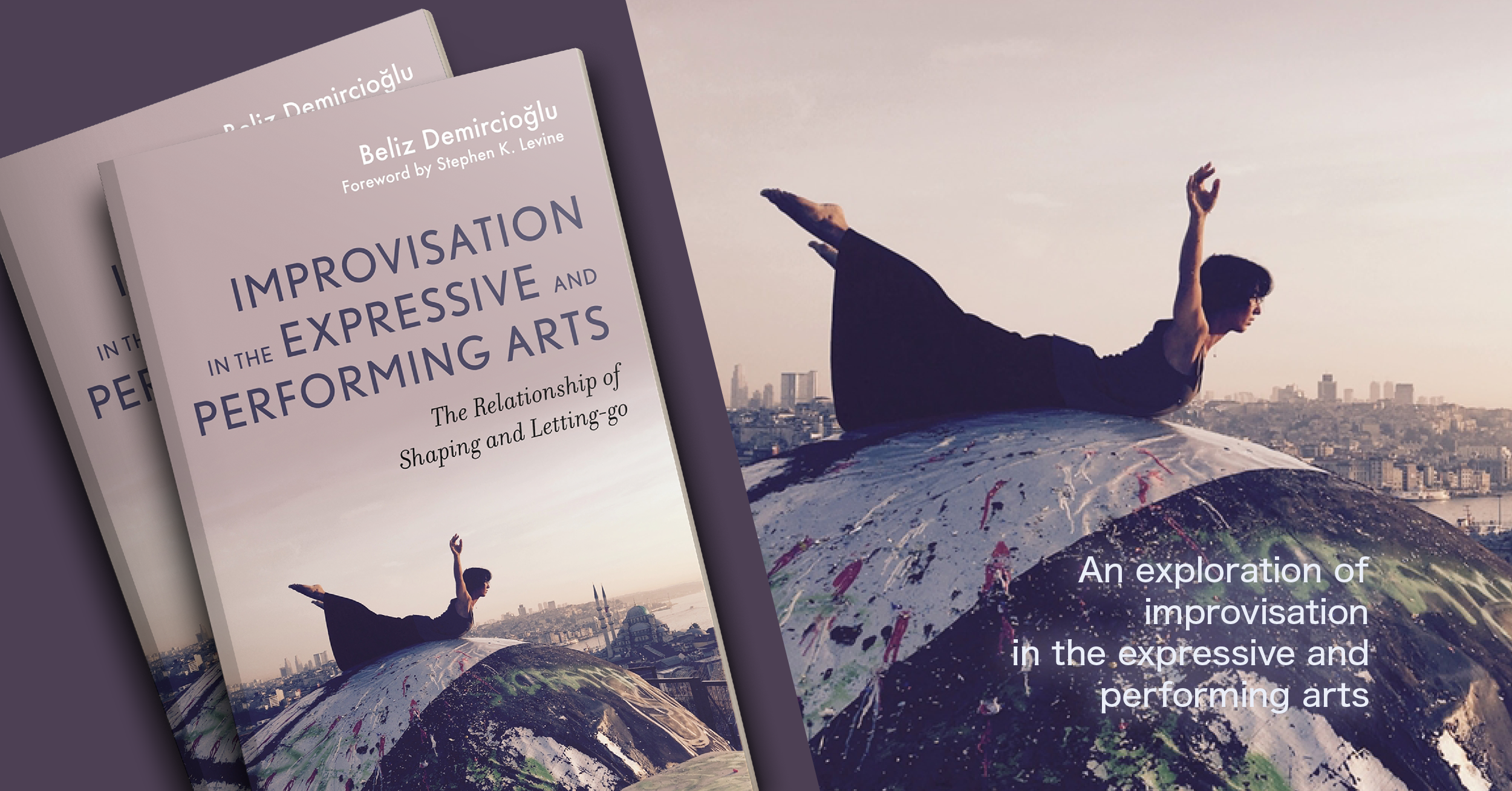

In a museum in Istanbul, the dancer stands on a stone about one meter square, set several feet above the ground. She has very little room to move. Nevertheless, she dances, improvising movements in response to the limitations of the space and the surroundings in which she is performing. Her movements seem unpremeditated. There is no set form, but each variation seems to fit just right in the sequence. Suddenly water flows down from the ceiling above her, bathing her while she dances. Her movements change in response.

The dance is beautiful.

This is what I remember from a performance that I saw several years ago by Beliz Demircioğlu, the author of Improvisation in the Expressive and Performing Arts. I had known her as a student in my doctoral classes in philosophy and research at the European Graduate School in Switzerland, where she seemed to be an attentive listener and a somewhat shy but insightful contributor to class discussions. However, I was unprepared for the effect that her performance had on me. I felt moved, touched by the effortless delicacy and power of the dance. It was as if the limitations she had set helped her open to a realm of new surprises, where unpredictable forms could emerge to create a whole.

I had the same experience while reading the dissertation on which her book is based. Nothing is predictable, yet each part seems to fit. Much to my surprise, the book itself has the same impact now each time I read and re-read it, as if the writing was itself a work of art that touches and inspires me and to which I can return over and over again. I say to myself, “Remember this!” as if my own thinking about always is exemplified in this work and, in fact, carried to new heights.

This book about the transformative power of art is itself transformative. It takes me into my own practice as a performing artist, as a therapist, and as a social change agent, reminding me to be open to whatever emerges, to never approach another person or group with a preconceived conception of who they are and what they are capable of; indeed, never to approach myself that way, but to always be open to new possibilities that will lead me to a future yet to be determined.

I believe the effect of the book rests on the transformative experience of the author herself. Beliz Demircioğlu opened herself up to a research process in which the outcome was unknown. Exploring the relationship between letting-go and shaping in movement improvisation with her research subjects—or better, collaborators—she participated in and responded to the experiences that they had in her studio, using in each case different art forms that fitted with what was emerging. This is research as poiesis, a process as much of letting-go as of shaping.

Beliz Demircioğlu put herself at risk in her research. She gave up knowing in advance what would happen and being in control of the process. Instead, she let herself go in response to what was emerging in relation to the other person, and found different means of creating that responded to the impact that the other had on her. The result was that not only were the people she worked with changed by the intensive improvisation processes in which they engaged, but she herself also underwent a transformation, one that affected not only her way of knowing but also her way of being, both in her art and in her life. This “effective response,” as we call it, can be attested to in her ability to keep going while her beloved nephew was dying from cancer. The research process was literally life-saving for her.

Consequently, I believe the reader will feel the impact of her discoveries as well as understand them. In this research process, feeling and knowing are intertwined, as they are in the creative process of art-making itself. Creativity is neither a matter of pure inspiration, following an impulse blindly, nor is it something planned in advance according to a presupposed idea. That is to say, to use the Turkish words, it is neither edilgen, a state of passivity I surrender to completely, nor etken, an act that is deliberately planned. The very opposition active/passive severs the two phases of the creative act that are themselves always in relation to each other.

In letting-go to what is coming, I am always aware of my response without reflecting upon it from a distance. I shape what comes according to my aims and the material that is given to me. And in shaping, I am still receptive to what seems to “work” in the forms that emerge. As Beliz underlines in her text, creativity in art and life cannot be understood in terms of the dichotomy active/passive. Rather, the interplay of letting-go and shaping that are mixed in creative emergence is best described as a process of letting-be, one in which passive and active are never totally separated but mutually interpenetrate at different phases of discovery. The reader can see in the careful descriptions of her work with, not her “subjects,” but what she calls her “Divers,” those who allow themselves the risk of delving deeply into something that they cannot completely control or understand. The reader can only gain an insight into this process if he or she is willing to immerse him- or herself in these experiences. In other words, we all must become “Divers” to be able to read the book in the way it demands.

Why is it so difficult to do research in this way? For the same reason that it is difficult to make art or, for that matter, to live our daily lives this way. Human beings survive in vastly different environments by knowing and controlling what confronts them— or at least, so it seems. In reality, our knowledge is limited and our capacity to control the world is even more so. Life demands improvisation, as does art. But both living and art-making also require that we engage with what or who confronts us without knowing how we will react. And that means giving up the sense of safety that we can acquire in dominating the other by means of a preconceived plan of action. This is why we have “performance anxiety” when we wish to enter a creative process and why we continually resort to habit and preconceived ideas that interfere with our capacity to “dive” into the work. As Beliz states, we need to sensitize ourselves and let-go in order to create. If we can, we then enter a liminal state in which our resources are put into question. We may then become confused and frightened and look to another to help us overcome this state. This is why we search for experts and authorities that supposedly know the way. But an artist, a therapist, or any other change agent who leads us out of the wilderness betrays her vocation in doing so. What the leader must do instead is provide the support that will help us stay in chaos and will enable us to call upon our own resources, those that can lead us to take the next step, a step that had been covered over but can now be discerned.

I believe that that help can come through a reading of this book, a reading in which we let-go into the text and shape a response to it that is uniquely our own. In other words, the book, to be properly understood, demands a creative act on the part of the reader, one in which we fully engage ourselves with this work and let ourselves be changed in response. I wonder how many of us are willing to take this risk. All I can do is assure potential readers that the result may be well worth it, that surprises may come that can be life-sustaining and life-affirming. I wonder what my own response will be. Truly, I do not know in advance, but I hope I will be willing to take the chance. And, dear reader, I wonder, will you?

This blog is an adaptation of the book’s Foreword by Stephen K. Levine

Beliz Demircioglu is a dancer, teacher and choreographer. She has performed extensively in New York, Istanbul and around Europe and currently teaches movement technique and improvisation classes for performing arts students at Istanbul Bilgi University, Turkey.