Ruth Churchill Dower discusses the motivations behind writing her book, and the importance of the arts and creativity for children.

When Daniel’s dog died, he showed no outward signs of emotional response to the death of his best friend. Not speaking was de rigueur for this four-year-old. In fact, he tried hard to avoid drawing any attention to his movements or expressions. Until the day our dance artist worked in his nursery. She offered curious provocations with unusual, tactile materials, spent time interacting with the children through movement and carefully chosen music instead of words.

Daniel became gradually engrossed in this music and, donning his favourite ballerina dress and grasping a tambourine, delineated long, graceful lines with his body to the rhythms. He didn’t appear to see or hear anyone else and, even when the music faded out, his body carried on moving, immersed in, and responding to, forces beyond our understanding. At this point he sang a simple song about his dog having died and being happy in heaven, whilst his body continued to make graceful shapes with the tambourine across the space. None of his educators or parents had witnessed this depth and intensity of his bodily and verbal expression before. Afterwards Daniel talked about his dog almost every week.

This, and many similar examples in early years settings, are the reason why I wrote this book. I have worked in the arts and early year sectors for 20 years and it never ceases to amaze me just how simply the arts seem to cut to the heart of what are otherwise quite complex issues. Take Daniel, for instance his story is not unusual for children who don’t speak, for whatever reason. In many settings, drawing, dance, storytelling, puppetry, music, sculpture, singing or photography are all used as powerful tools to help children express through their bodies the feelings that they can’t verbalise. Some of these children work well with Speech and Language therapists or Educational Psychologists, for instance, but others benefit from a more creative, spontaneous approach that unlocks the possibilities inside them without having to put a label on what this might mean.

For instance, we might naturally look for some kind of meaning in a child’s drawing so that we can understand them better. We might ask them what it is or observe how it represents their progress in language or literacy with the shapes of letters or the fluency of the lines. But for a young child, drawing is often more a way of feeling the enormous emotions and energy within their bodies, and expressing this on paper in the twirls and movements of their arm as they draw, the weightiness of some lines and the lightness of others, the positioning of the shapes and colours next to each other, the texture of the marks once they have been transferred from the head + body onto the paper or board, not to mention what is going on with the rest of their bodies to help express those feelings as the drawing takes place. A young child isn’t necessarily making something important, they are doing something important. And the same is true for every art form.

Because of the ways in which young children learn multimodally (such as visual, linguistic, aesthetic and kinaesthetic) often all at once, they can also express themselves in these ways. Their modes of reception and communication don’t become compartmentalised into areas of knowledge and skill until their brains and bodies have developed a sense of reasoning much later on in Primary school. Therefore, the arts offer fantastic ways to nurture children’s natural abilities (across all areas of learning), to stimulate their imaginations and curiosity, and to help them make themselves understood.

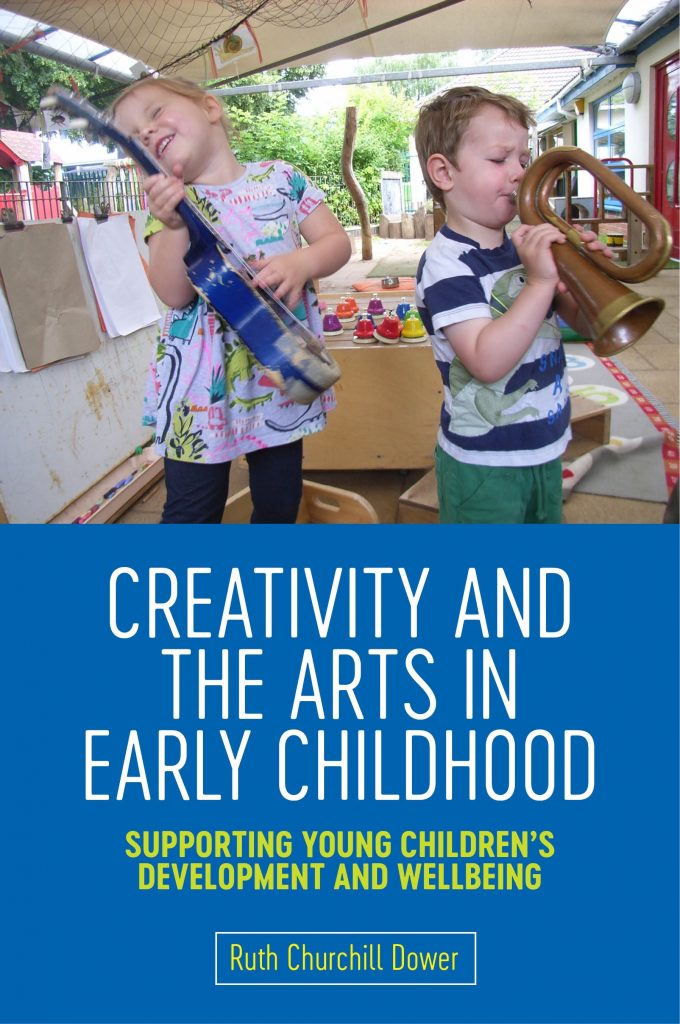

This book helps us understand what the theory is behind those ideas, and how to put it into practice in both early education and cultural settings and how to link it across the whole Early Years Foundation Stage curriculum. The book focusses in the first half on what creativity is, how we can spot and nurture it, how we can create the right conditions to allow creativity to flourish, and whether it is even possible to measure it like we try to measure other areas of learning. The second half looks in more detail at using different art forms, giving practitioners, teachers and parents alike a wealth of ideas on how to build an enormous arts-resource in their own setting or home, and understand how to help facilitate their child’s most innovative, mind-boggling and courageous ideas. Covering the ages of a nought-to-five year old, this book sets out to explore the many different creative environments that could be possible, why this is so important in a child’s earliest years and, at the same time, how to remove the barriers to our own creativity as adults.

More details here.

If you would like to read more articles like this and get the latest news and offers on our early years books, why not join our mailing list? We can send information by email or post as you prefer. You may also be interested in liking our Special Ed, PSHE and Early Years Resources Facebook page.