What can kids learn from The Kids’ Guide to Getting Your Words on Paper?

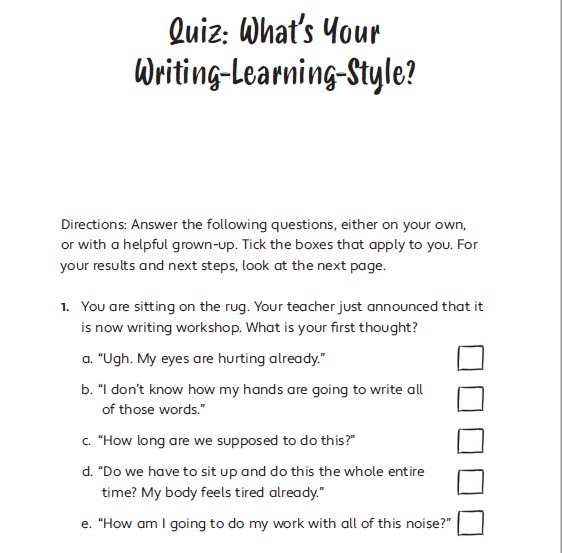

By taking the quiz in the beginning of Kids Guide, they can understand what may be hindering their ability to write (visual motor, fine motor, attentional, postural, etc.). Once they understand the primary blocks, they can then go to the corresponding chapters connected to those areas.

Within each chapter, they will see any and all required equipment (kept to a minimum for accessibility) and exercises. At the end of each chapter, kids have a concrete schedule to follow on a daily basis with the provided exercises and tools to complete before writing tasks that should organically improve the skill on a daily basis. There are self-monitoring visual checklists at the end of each chapter to help kids determine their “just-right strategies” and to help them ensure that they are completing these exercises on a daily basis.

Can you briefly outline your history working with kids and teens? How has this background influenced what you write about?

I have been a pediatric occupational therapist for over ten years. Working in the school system has really helped shape my practice, as I saw the need for children (and their helpful grownups—whether teachers, therapists, or parents) to have access to easy-to-implement, consistent supports across their day, along with an understanding of the purpose of why they are utilizing them.

How can The Kids’ Guide to Getting Your Words on Paper be used in a classroom or other school setting?

Teachers can use the quiz in the beginning of the book to help students determine their writing blocks from a developmental skill perspective. The quiz is short and clear and can easily be photocopied or projected in front of a class. Teachers can then break students up according to needs and can work through connected chapters to review related exercises and tools with each group. At the end of the chapter, there is a suggested sequence of completing exercises and utilizing tools to consistently improve the specified skill over time, preferably before writing tasks. Teachers can use this tool to work with kids to ensure the daily activities are completed.

What was your inspiration for The Kids’ Guide to Getting Your Words on Paper?

As a pediatric occupational therapist who works often in the school setting, I have seen the benefit of providing students with concrete tools and supports within the classroom setting where they are able to work on underlying skill component areas of difficulty over time in meaningful ways, moving away from direct therapeutic intervention. That idea was the inspiration for this book.

In the past couple years, so much research has been done on neurodiversity and how kids learn differently. What are small steps educators can take to ensure all kids are getting the best out of their school day?

It is important to remember that students do not fit into a standard box. Combining whole-class RTI, such as language around self-regulation, adaptive seating and sensory supports, with differentiated interventions works better for a diverse classroom setting. It is also key to remember that it’s ok if a child may need to lay on their belly during instruction on the rug to learn best, that the child looking away is still hearing you, that the student about to run out of the classroom may need a quiet safe space put into place proactively, and that all kids may have hard days, sometimes (just like us!). Ensuring that your students’ foundations for learning are met, such as safety, consistency, and regulation is a nice first step to allow for higher level learning to take place.

Some simple tricks include:

- Playing low frequency music for a calming environment or high frequency music for a more alert time

- Bright lights are alerting, and low lights and natural lights are calming.

- Having your students lower their heads below their knees is calming and can get them out of fight or flight; having them firmly tap their limbs is alerting.

- When students are on the rug, try to ensure that they are sitting for no longer than one minute per year of their age, followed by a movement break. You can use a visual timer, to give both yourself and students an idea of how long they are expected to be attentive.

- Using language to have kids name challenging emotions, from a physical or emotional standpoint, with connected exercises and tools, can be very helpful from a regulation perspective as well; that was the motivation behind the creation of my first book, The Kids’ Guide to Staying Awesome and In Control.

With all the stress about COVID-19 at the moment, what are some ways we can help young people with dyspraxia?

I believe that taking into account the whole-child is, as ever, vital to ensure that children diagnosed with dyslexia or other conditions are able to learn, thrive, and complete day-to-day tasks confidently and in a functional manner.

Breaking down tasks into small steps, accompanied by visuals/other sensory feedback, is one way to assist in having your child complete chores and assignments that involve larger chunks of information. This strategy can assist in the skill relating to motor planning, connecting to ideating a motor plan, and functionally executing it.

Consider having your child complete large movement/gross motor crossing midline activities (where one side of the body crosses to the other side) before sitting down to complete work or activities requiring coordination/focus. This leads to “cross-hemispheric integration”-where one side of the brain speaks to the other. This is helpful for focus and body coordination!

As we are living in a time where children are bombarded with news and information that can sound scary, even when we as adults do our best to shield them from the worst of it, providing our children with self-regulation tools that they can independently utilize when feeling anxious can really help control those feelings. A great strategy that I have found to be beneficial that I use clinically and with my own children is from my second book, How to Be a Superhero Called Self-Control: “Mantra.” Have your child come up with their own positive affirmation that they can utilize when feeling stressed. They can draw it out and/or write it out and place it somewhere visible to remind them to utilize it during times or emotional dysregulation. Examples include: “I am loved,” “I am safe,” “It will be ok.”

To learn more about dyspraxia: https://blog.jkp.com/?p=19647