When the topic of asexuality being represented in media comes up, there is often one common question that comes along with it: Why do asexuals need representation? How do you represent…doing nothing?

It can be quite hard for people who aren’t asexual to understand that not experiencing sexual attraction is not the same as the points in life where you’re single, or simply ‘not having sex’ whilst in a relationship. I’ve seen many people argue online: ‘There’s plenty of TV shows where people aren’t having sex, so you already have what you want there’.

But they’re missing the fact that, for the majority of people, physical intimacy and relationships/romance are intertwined, and people within the asexual spectrum are often painfully aware of this. Asexuals often want relationships, demisexuals and grayaces sometimes want physical intimacy, aromantics aren’t necessarily happy with being alone. We are definitely doing more then ‘nothing’ when it comes to relationships. We’re navigating something incredibly complicated, and sharing these complexities in media can be truly helpful!

Lack of representation played a large role in my own difficulty in discovering I was asexual but still looking for a relationship. It wasn’t just that asexuality was non-existent in media, but that it was non-existent everywhere.

I didn’t know anyone who felt the way I did (at least not openly).

And I had grown up believing, through media and real life, that anyone not interested in getting physical was a sociopath, ‘not ready yet’ or dealing with serious intimacy issues. I couldn’t bring up the fact I didn’t like something as simple as kissing anyone I crushed on to friends – it felt like something really shameful, like people would accuse me of having some serious mental health problems. My own therapist at the time certainly put it down to that.

At the time, media was the only place I could turn to in order to explore my embarrassing problem of being a voluntary virgin at age 20. But, media only made things worse. The only people I found on TV/books who didn’t like sex were serial killers, sociopaths, losers, or people who just needed ‘true love’ to fix all their intimacy problems. Even in Disney movies, it was made very clear to me that the only way I’d ever find love was by doing things that made me seriously uncomfortable – hugging, holding hands, and of course, true love’s kiss. Through real life and the stories I turned to, I became convinced there was something seriously wrong with me. Even worse, I felt this was something I should never talk about, and that I would end up being completely alone. I was getting a clear message: a loving relationship could not exist without physical intimacy, otherwise it just isn’t real love.

Thankfully for me, after a couple of years of extreme guilt and loneliness, I discovered the little known term ‘Asexuality’. It’s amazing how finding a label for ‘doing nothing’ can help someone so much. I know for sure that if there had been more normal, complex characters ‘doing nothing’ in media relationships, I wouldn’t have wasted so much time agonising over the future of my relationships.

I hope I’ve established the impact representation can have on asexuals, but how can it impact those who aren’t on the ace spectrum?

Much to my surprise, after I graduated from university, I did end up falling in love with someone, who also happens to be asexual (lucky me!). Around the same time, I came across the TV adaptation of ‘Brideshead Revisited’, and the first romance I ever saw that very much looked like my own. It was very clear (and even stated!) that Sebastian and Charles were in love. And yet they never held hands or kissed, their love instead shown through the closeness of their emotional relationship.

At the time, I felt really validated and really happy to see a romantic relationship that was same sex (like mine) and also non-physical (like mine). Charles and Sebastian’s relationship was truly romantic and loving, so that meant mine was too, no matter how many people might question how I choose to express love to someone.

Over the years though, my interpretation of this story has been aggressively criticized. Why? Because many people view the relationship in Brideshead Revisited to be a sexual relationship (since the writer of Brideshead was indeed in several sexual gay relationships). And, since I interpret the relationship as asexual, that apparently means I’m denying the romance between the two gay characters – or so I’ve been told.

But my answer to this criticism is: by suggesting that I’m denying a romance through adding the asexual label, you’re suggesting that my own gay relationship is not real or romantic enough for you. Do these people who criticize my interpretation of one story also think that I don’t truly love my girlfriend as much as those who are in physical relationships?

The amount of “have you both tried (insert something way too graphic to be asked in public here)? You should really try that, how do you know you don’t like it if you haven’t tried??” myself and my partner have heard, suggests that’s often exactly what people think.

This anecdote hopefully shows the impact that more representation could have on everyone. The more rep we have woven into stories, the more people will understand asexuality and accept it.

Perhaps more people will see that you can have happy, healthy asexual relationships, and will stop forcing you to see therapists that make you believe you need to force yourself to do things you don’t want. Maybe parents who want traditional extended families will stop thinking their children being disrespectful on purpose when they don’t seek partners.

And hopefully, more people will stop forcing others into sex because ‘waiting until they’re ready’ isn’t something to be respected or real, only a suggestion that a partner doesn’t truly love them.

See how the experience of asexuality is about a lot more then ‘doing nothing’?

Representation can make people across all sexualities and experiences feel that they have meaning or a place within society. It also helps to break myths, educate and validate our existence to other people. The same goes for people across the asexual spectrum, and I hope we continue to see more and more asexual rep across the media! Thank you to everyone out there who is already beginning to make that a reality!

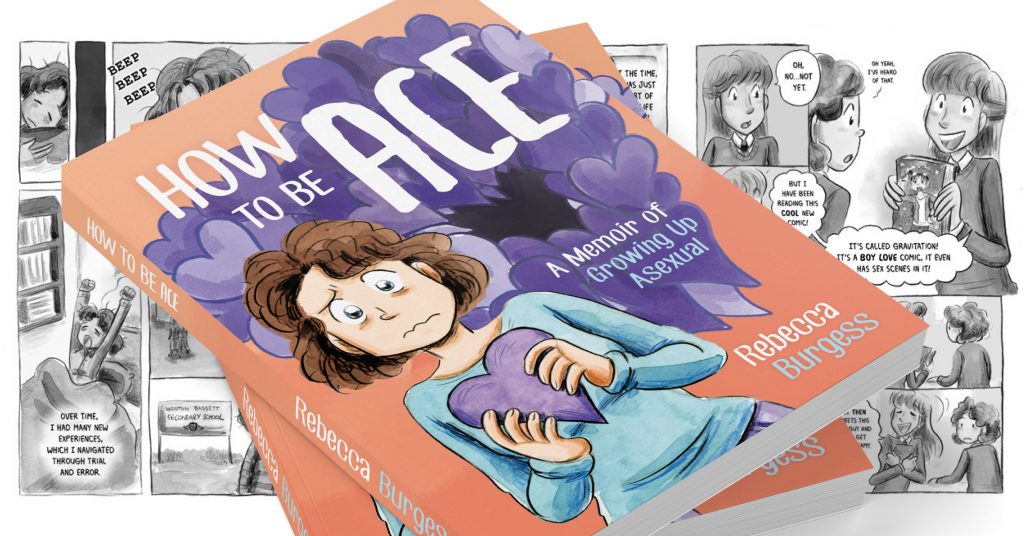

Rebecca Burgess is a full-time autistic illustrator who identifies as asexual. Their comics have featured in The Guardian, and they love telling stories. How To Be Ace is their first book. It’s out tomorrow, 21st October 2020.