Encouraging empathy and inclusivity through shared book reading

In honour of Anti-Bullying Week, hear from the authors of ‘A School for Everyone: Stories and Lesson Plans to Teach Inclusivity and Social Issues’, Ffion Jones, Helen Cowie and Harriet Tenenbaum, about how teachers can promote empathy and inclusivity through classroom activities.

Anti-bullying week, coordinated by the Anti-Bullying Alliance, is an annual event empowering everyone to unite against bullying. “One Kind Word,” the theme of Anti-Bullying Week 2021, which runs from 15th – 19th November, focuses on how little acts of kindness can make a huge impact and how we should all respect each other’s differences. So how do we encourage children to engage in these little acts of kindness and accept differences and diversity?

One key factor is encouraging empathy in children. Empathy is a skill that we can develop so that we can more easily understand the perspective of others. Perspective-taking allows children to imagine themselves in the shoes of someone else so that they can understand how others may perceive the world. Children can then use this understanding to adjust their own view of others, which can help to reduce prejudice or bias based on stereotypes.

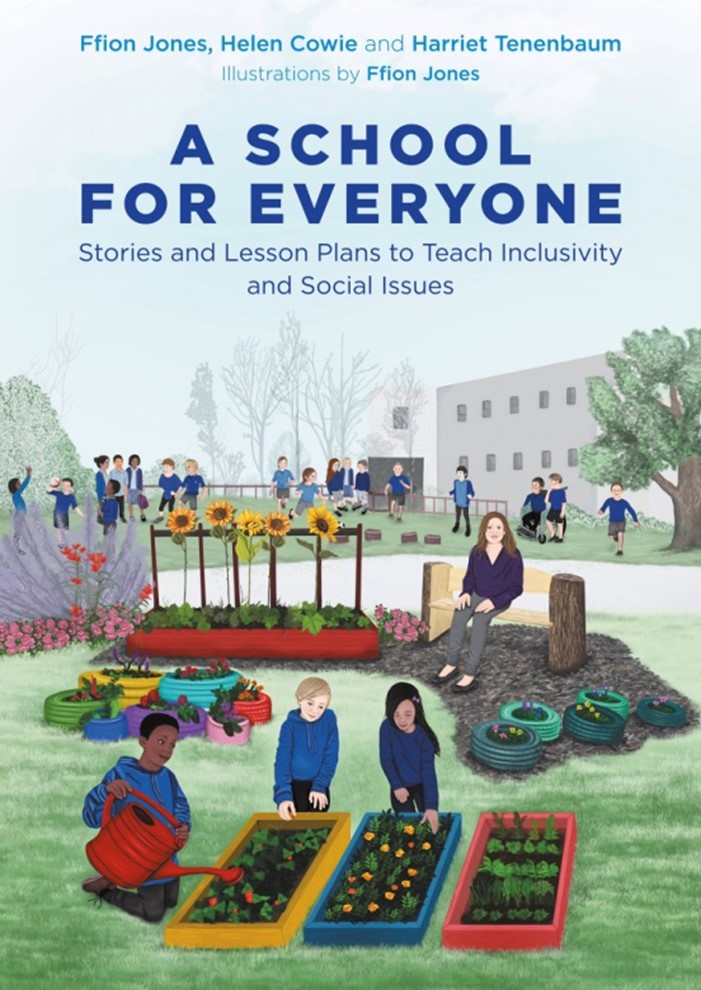

Book reading can help to nurture children’s empathy skills by allowing them to practice perspective-taking and imagine what other people may feel in certain circumstances. ‘A School for Everyone: Stories and Lesson Plans to Teach Inclusivity and Social Issues’ is a research-informed empathy-building discussion tool for educators that encourages respect for individuality, shows multiple perspectives, and highlights how young people can make a difference. By increasing knowledge and understanding of a wide range of social and emotional issues, the book promotes acceptance and celebration of diversity in the school environment so that all classmates feel valued and included.

The compendium provides 16 stories told from the different perspectives of individual children from one class over the course of three terms. Each chapter opens with discussions about tricky topics including gender diversity, bereavement, disability, body image, frenemies, cyber-bullying, parental divorce, living in poverty, and climate change, to help children develop empathy for their peers. Shared reading of a story gives each child insight into the inner thoughts of a character who is experiencing distressing emotions. Alongside classmates who are facing these difficult issues, we also meet Jakub who is from Poland, Molly who is not a stereotypical girl, Oliver who is on the autism spectrum, Jamie whose dad is in prison, Hind who is a refugee, Margaret who is from a gypsy family, and Michael who learns about important Black Britons. By reading their stories, young people start to imagine what it feels like to be one of them – the building blocks of empathy.

For each issue raised, the story is followed by a fact file, a set of interactive activities, lesson plans and a bank of resources to further enhance understanding and promote empathy. Research suggests that guiding children’s learning and supporting them to interact with peers can help children learn more than working on their own. The activities are designed for children to work together to support their learning. The group setting seems to provide a supportive space in which to explore the implications of the events of the story for the characters. In this social context, existing beliefs about the topic or about the cultural background of the fictional characters can be safely explored. Reading together in a group setting appears to enable participants to internalise the experiences and emotions of the fictional characters, reflect on these characters’ inner thoughts, and consider these fictional happenings in the light of their own lives. Furthermore, in the group setting, the perspectives of all the listeners converge as they collectively consider the issues and dilemmas raised in the story. Bystanders can reflect on the positive impact of just one kind word. Marginalised children can gain hope that there are solutions to difficult situations. Children who bully can see the effect of negative behaviour on the character in the story.

There are several characteristics typical of children exhibiting bullying behaviours – and a lack of empathy for the distress that their actions cause is a key characteristic. One way to increase empathy is through real or “imagined” contact. Research studies have found that when people from different groups make contact with each other, prejudice is reduced and relations are improved. For example, one study found that when children attend schools that are more ethnically diverse (real contact), they are more likely to say that it is wrong to exclude someone in peer contexts based on their ethnic background than if they attend less ethnically diverse schools. However, there are two ways in which contact is difficult. First, reduction of prejudice can only work when there is an opportunity for contact. Some schools may have low levels of diversity so that children do not have the opportunity to interact with people who are different from themselves. Second, sometimes people become anxious about interacting with someone who is different from themselves, preventing contact from reducing prejudice. This is another reason why the concept of imaginary contact becomes so important. Imagined contact can reduce children’s future anxiety about meeting people different from themselves.

Researchers have found that imagining an intergroup interaction can have many of the same effects as actually participating in intergroup contact. Indirect contact through reading books has been found to have this positive effect on children’s intergroup attitudes as well as increasing desire to engage in future contact. In an article in Psychology Today, Christopher Bergland discusses how reading the Harry Potter series has been found to improve children’s attitudes towards stigmatized groups in real life. Researchers observed a reduction of prejudice as children put themselves in the shoes of the marginalised characters in the books.

Reading stories about people who are marginalised or different in some way and leading children to imagine interacting with them – imaginary contact – can therefore be a powerful force for change. The first-person stories and activities in ‘A School for Everyone’ aim to create contact, offering multiple opportunities for children to empathise with the voices of different characters and see things from another’s point of view. This can lead to more compassionate and inclusive classrooms, where diversity is celebrated. Just as one kind word can lead to another, our hope is that “A School for Everyone” can make a difference.

Order ‘A School for Everyone: Stories and Lesson Plans to Teach Inclusivity and Social Issues’ here