What’s It Like Being Both Dyspraxic and ADHD?

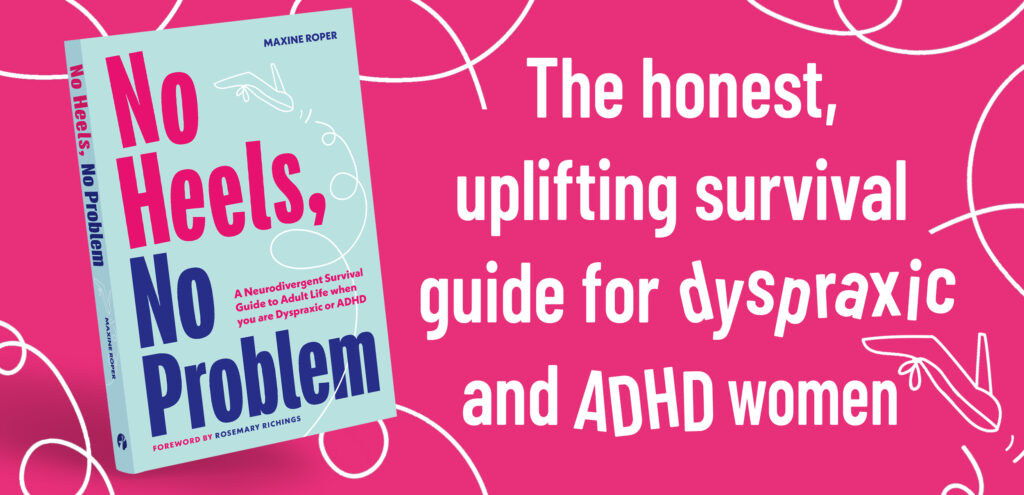

Q&A with Maxine Roper, author of No Heels, No Problem

Maxine Roper is a dyspraxic, ADHD writer. She has written about neurodivergence for fifteen years and her pieces have featured in a variety of outlets including The Guardian and The Daily Telegraph. She is also a Fellow of the Royal Society of Arts and a former Trustee of The Dyspraxia Foundation.

You describe your book as the survival guide you wish you’d had growing up, what was missing back then?

In a word, understanding. I grew up in the 1990s, so I just had no vocabulary to describe many of my experiences and nor did anyone else. The written word came naturally to me from an early age, so I always wanted to be a writer, and did well in lots of areas at school. But I struggled in lots of other areas too, and as I grew up, the struggles increasingly seemed to undermine my strengths and expanded into ever more areas of my life. I was prone to fixations, which increasingly led to unhappy fixations with people who I thought were better at life than me. I now know fixation in general is a very common neurodivergent trait and can apply it to healthier things.

How would you describe being both ADHD AND dyspraxic?

ADHD affects executive function, which affects attention control, mood, motivation, short-term memory and your ability to prioritise and plan. Dyspraxia means that things that require dexterity are harder for me. Together they affect pretty much everything to do with moving through the world. They can also feed off each other unhelpfully. As I mention in the book, exercise often helps people with their ADHD, but finding the right exercise is harder if you’re dyspraxic.

It’s now understood that different types of neurodivergence often go together or overlap, but, like me, most people are screened for one at a time and people are increasingly having to wait for years even for a single diagnosis, so a lot of people aren’t getting the support they need.

Dyspraxia and ADHD specifically are both thought to be related to neurotransmitters in the brain, and I’ve personally found that medication for ADHD helps with both, but haven’t seen this researched or talked about.

What do you wish more people understood about how neurodiversity affects everyday life and emotional wellbeing?

Firstly, how vital a diagnosis is for some people and the impact being undiagnosed can have on life. Everyone finds things hard at times, but most people get better with

practice or by challenging themselves to do more things. If you’re neurodivergent and undiagnosed, often a lot of things just constantly feel harder for you than for most people, and it’s harder to improve because you don’t know why, or people make the wrong assumpions about why, so life can just feel constantly overwhelming.

Hormones and the menstrual cycle can also hugely affect ADHD and dyspraxia, and I had no idea about this until recently. A complete diagnosis and the right support have been life-changing for me, but being able to enjoy and manage life is never something I take for granted, especially when it comes to big life changes.

I don’t expect everyone to be experts on dyspraxia or ADHD, but I’d like people to respect that it can mean my experience is different from theirs and what seems simple, helpful, important or fun to them might not be for me, or for everyone. I also wish fewer people believed that shame and judgement are the way to motivate people with long-term problems.

How long ago were you diagnosed? Did that impact how you felt about your neurodiversity?

My dyspraxia was diagnosed at university in the early 2000s, and my ADHD five years ago in my mid-30s. The dyspraxia diagnosis came about because my degree had a module in social research and due to my lifelong struggle with Maths, I was worried I wouldn’t manage. It explained a lot about my childhood and made me realise I wasn’t alone in my uneven abilities, but it didn’t quite seem to explain or help with everything. By my thirties, my life was still a vicious circle of anxiety that I seemed increasingly unlikely to grow out of. I went into long-term therapy, took up running, then reluctantly started to accept that some sort of medication might be helpful as well. By then, people were starting to recognise ADHD and autism in women, and these often went along with dyspraxia and dyslexia. I started seeing accounts of how an ADHD diagnosis and medication had worked for people. When I got both, I wept with relief.

What was the writing process like?

I was in the middle of writing a novel when I got my diagnosis and because it was such a relief, ended up putting the novel on hold to write this book instead. It was a long writing

process – four years from start to finish, partly because the conversation about neurodivergence was moving and changing all the time and I was trying to keep up.

My ADHD medication helped to keep me consistently focused and motivated, which was wonderful after decades of trying to write without either. But structuring my ideas was still challenging. At one point, the first two chapters were half the book and I didn’t even notice! I worked with a Development Editor to help me with this.

The ‘spiky profile’ of strengths and challenges or highs and lows that’s common to neurodivergence can be hard to write about without downplaying one or the other. Getting that balance right felt very important to me.