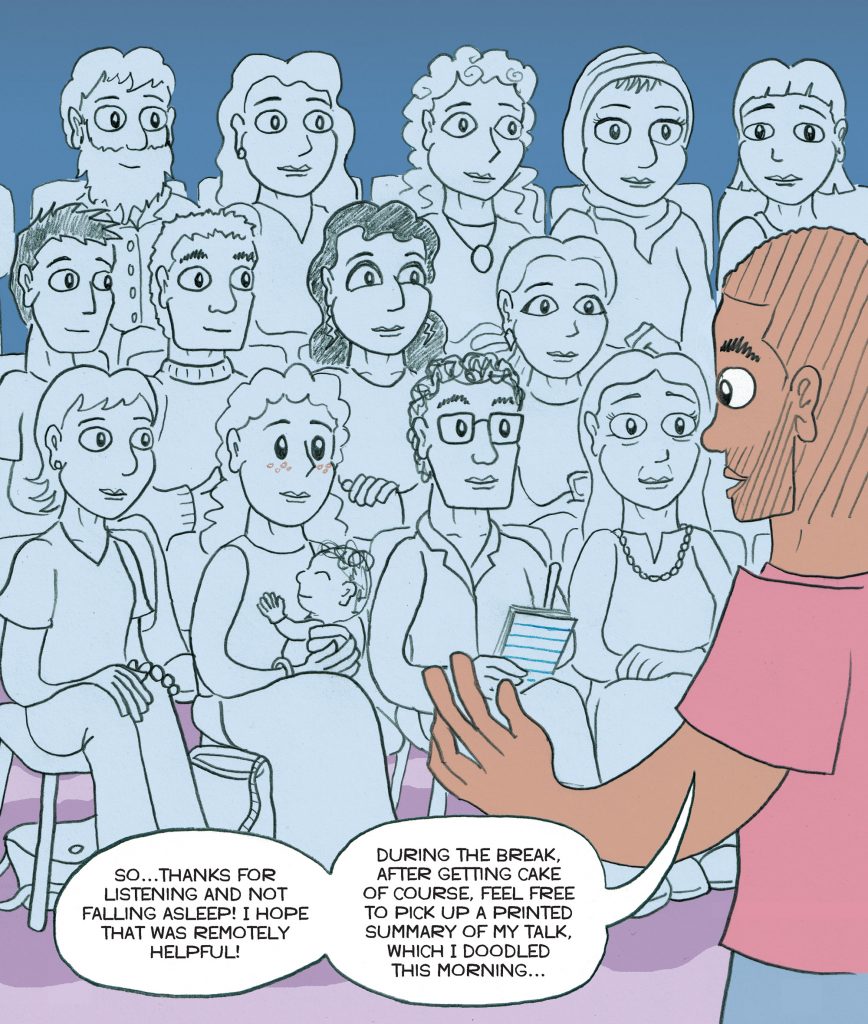

Richy K. Chandler author of You Make Your Parents Super Happy! and When Are You Going to Get a Proper Job? talks through the challenges that come with creating diverse characters in stories, and why it is so important to do.

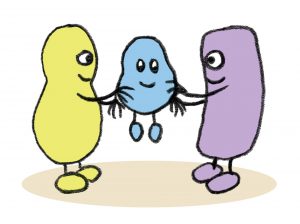

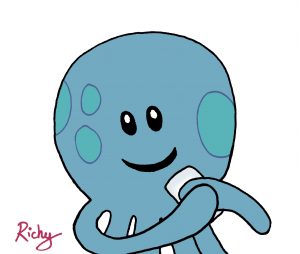

When I was working on You Make Your Parents Super Happy! (my recent picture book for children whose parents have separated but still both want to be part of their child’s life), I was conscious of keeping the gender and race of all characters ambiguous. While the book deals with a very specific situation, I hope that the universality of the characters’ appearance means that as many children and families as possible can see themselves as the beings found within the pages. This could be two dads, a mum and a dad, two mums and a multitude of relationships also representing the full range of cultures and ethnic back grounds that exist. Similarly, with Lucy the Octopus, my webcomic that looks at the effects of bullying and bigotry (hopefully in a humorous and super cute way), I wanted to make the lead character as universally relatable as possible. The strip touches on racism, homophobia and not fitting into gender stereotypes but it’s never made clear exactly why Lucy, the heroine, is so unliked. Lots of readers have told me that they see part of themselves in Lucy, and not always for the same reasons. I’m usually both happy that the character is relatable and saddened for the readers to have gone through similar horrible experiences.

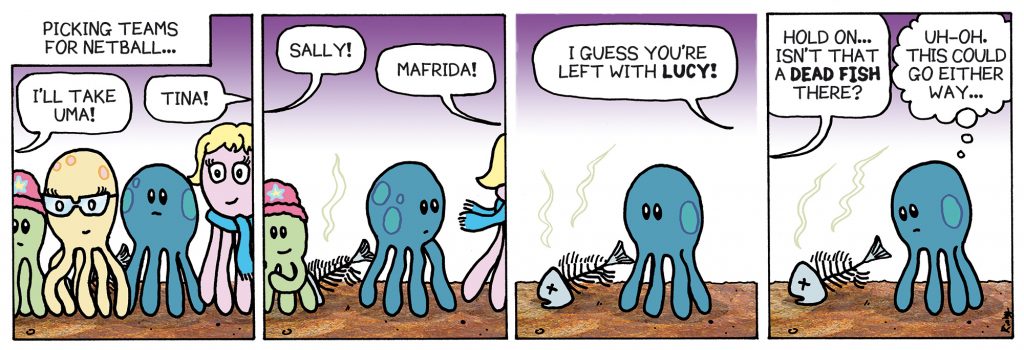

Similarly, with Lucy the Octopus, my webcomic that looks at the effects of bullying and bigotry (hopefully in a humorous and super cute way), I wanted to make the lead character as universally relatable as possible. The strip touches on racism, homophobia and not fitting into gender stereotypes but it’s never made clear exactly why Lucy, the heroine, is so unliked. Lots of readers have told me that they see part of themselves in Lucy, and not always for the same reasons. I’m usually both happy that the character is relatable and saddened for the readers to have gone through similar horrible experiences.

As a writer who has no desire to create comics starring myself (hats off to those brave enough to make candid, graphic autobiographies), there are other good reasons for making characters more universal. With Lucy the Octopus, I wanted to talk about experiences of feeling picked on and ostracised in my own school years, but I’d rather avoid the spotlight being on myself. Making Lucy a girl and an octopus certainly did that job and frees me up to wildly exaggerate my own experiences within her fantastical world. For example, my own family were not terrible to me like Lucy’s are (except that year I got Scrabble for my birthday instead of the Crossbows and Catapults game I’d wished for, but I’m a survivor and made it through that bleak day).

As a writer who has no desire to create comics starring myself (hats off to those brave enough to make candid, graphic autobiographies), there are other good reasons for making characters more universal. With Lucy the Octopus, I wanted to talk about experiences of feeling picked on and ostracised in my own school years, but I’d rather avoid the spotlight being on myself. Making Lucy a girl and an octopus certainly did that job and frees me up to wildly exaggerate my own experiences within her fantastical world. For example, my own family were not terrible to me like Lucy’s are (except that year I got Scrabble for my birthday instead of the Crossbows and Catapults game I’d wished for, but I’m a survivor and made it through that bleak day).

The starting point of the Lucy character was making her a stand in for myself, but from there I could shape her to be more consistently kind and sweet and generally more likeable. She can have a neater complete story arc than my own too.

There are problems with making characters too universal though. Culture loads character designs with meanings which aren’t necessarily intended.

There are problems with making characters too universal though. Culture loads character designs with meanings which aren’t necessarily intended.

People have made assumptions as to the gender of the parents in You Make Your Parents SUPER HAPPY! I also wonder if readers will assume the child is male simply because they are coloured blue.  When illustrating The No Panic Book of Not Panicking (Apples & Snakes), a book about dealing with stress and anxiety, again, the intention was for the characters to be readable as any gender or race, so I went with my own variation of stick people.

When illustrating The No Panic Book of Not Panicking (Apples & Snakes), a book about dealing with stress and anxiety, again, the intention was for the characters to be readable as any gender or race, so I went with my own variation of stick people. This seemed to cover all bases, but having given it further thought, a stick figure is problematic. For one thing, we see basic stick men on Gents toilet doors around the world, so this builds the assumption that a standard stick person is male. Aside from that, there were points in the book where it was key that the characters were depicted as female and further points where simply as a design choice to suit a particular illustration layout, some of the figures had darker skin. Does that create an idea that all the other characters in the book, the supposedly universal ones, must default to be seen as white males? I think this is certainly a risk.

This seemed to cover all bases, but having given it further thought, a stick figure is problematic. For one thing, we see basic stick men on Gents toilet doors around the world, so this builds the assumption that a standard stick person is male. Aside from that, there were points in the book where it was key that the characters were depicted as female and further points where simply as a design choice to suit a particular illustration layout, some of the figures had darker skin. Does that create an idea that all the other characters in the book, the supposedly universal ones, must default to be seen as white males? I think this is certainly a risk.  Lots of children’s picture book creators notice that children and parents often assume animal or other non-human characters in children’s books are male, unless it’s made explicitly clear they aren’t.

Lots of children’s picture book creators notice that children and parents often assume animal or other non-human characters in children’s books are male, unless it’s made explicitly clear they aren’t.

The culture I’m surrounded by seems to dictate that protagonists are largely males, and more often than not, straight, white ones. There are of course, notable exceptions but that is largely what creators default to. Sometimes male creators may make characters that mirror themselves, though creators of any gender may still choose to focus on male central characters, possibly through pressure from publishers or just subconsciously repeating the pattern we’ve seen in so much fiction before.

For example, watching Cartoon Network with my son, it’s easy to find wonderful inspired shows, some including great female characters (Steven Universe and Adventure Time come to mind), not just girlfriends and love interests. However with the exception of Powerpuff Girls, no shows on the channel mention female characters in their title or have female protagonists.

Cartoon Network is clearly not alone in this well-established trend. It’s obvious that there aren’t enough female central characters in popular literature, television and film, not just to work as role models or relatable focal points for girls and women, but to do exactly the same for boys and men too.

So, while there is certainly a place for characters designed to be read as universal, writers also need to chip away at the assumption that characters will most likely be male, and also that protagonists should be straight, white boys or men. As creators, we can do this by broadening our pool of diverse characters beyond just tokens and sidekicks, and having more diverse lead central characters. So with the Lucy the Octopus strip, I knew the main character had to suffer from ostracisation and being picked on – that was the theme of the strip I wanted to explore, but there was nothing in that which meant the protagonist had to be male, so Lucy was a created as a girl.

So with the Lucy the Octopus strip, I knew the main character had to suffer from ostracisation and being picked on – that was the theme of the strip I wanted to explore, but there was nothing in that which meant the protagonist had to be male, so Lucy was a created as a girl.

Of course, there’s nothing wrong in real life with a white person having a best friend who is a person of colour, or for a man to rescue a woman tied to a rail track (it’s probably the decent thing to do). The problem is that when we see these situations again and again in fiction, putting white males at the centre of our stories, it reinforces the idea of minority characters being secondary to the white leads, and women being passive and there to be rescued by men.

Viewers and readers of different backgrounds and genders can empathise with white male central characters and what they go through, to a large extent. There are obviously shared human experiences and emotions we can all understand – that’s not the point. The issue is that for a long time many viewers and readers have had little choice but consume fiction focusing on white males. There is zero reason white male audiences can’t do the same and enjoy stories centred around other types of character. Broadening the idea of what the “everyman” is, can only increase empathy and understanding for people that may on the surface, seem different to themselves.

Don’t get me wrong, characters exist to serve a story, and there may be a myriad of organic reasons for a character to be depicted a certain way. Balancing diverse representation and serving the narrative perfectly can be difficult, but only within the context of writing. The problems cemented by a lack of diversity amongst characters in media are real world and far reaching.

Don’t get me wrong, characters exist to serve a story, and there may be a myriad of organic reasons for a character to be depicted a certain way. Balancing diverse representation and serving the narrative perfectly can be difficult, but only within the context of writing. The problems cemented by a lack of diversity amongst characters in media are real world and far reaching.

Barely any of what I’m saying here is my own insight. As a straight, white male, my own experience is the least relevant in this discussion. I’ve picked up my ideas through various podcasts (e.g. Stuff Mum Never Told You and Witch, Please), books (e.g. Why I’m No Longer Talking to White People about Race by Reni Eddo-Lodge and Black and British: A Forgotten History by David Olusoga), websites (writingwithcolor.tumblr.com) and inspiring talks at London based comic events such as Laydeez Do Comics and Let’s Talk Intersectionality.

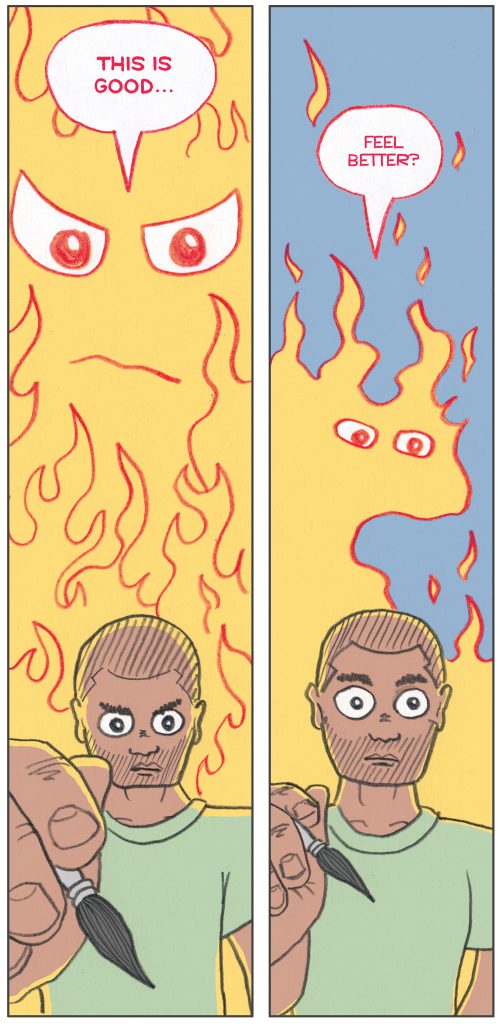

How ever well-intentioned my creative efforts are, in terms of depicting diversity, there will always be a blind spot (often a huge one) based on my limited perspective. In depicting the character of Tariq, a black guy who stars in my graphic novel When Are You Going to Get a Proper Job? struggling to balance life raising his daughter and pursuing his creative goals, I was lucky enough to have several black friends in comics who were kind enough to read draft versions of the book. Some saw no issues with my depiction, which was a relief. One friend gave lots of suggestions for if I wanted to make Tariq more specifically Caribbean. One pointed out that the nickname Tariq gave his daughter in one scene, “Weird Nose”, was problematic.

How ever well-intentioned my creative efforts are, in terms of depicting diversity, there will always be a blind spot (often a huge one) based on my limited perspective. In depicting the character of Tariq, a black guy who stars in my graphic novel When Are You Going to Get a Proper Job? struggling to balance life raising his daughter and pursuing his creative goals, I was lucky enough to have several black friends in comics who were kind enough to read draft versions of the book. Some saw no issues with my depiction, which was a relief. One friend gave lots of suggestions for if I wanted to make Tariq more specifically Caribbean. One pointed out that the nickname Tariq gave his daughter in one scene, “Weird Nose”, was problematic.

“Weird nose” was similar to the name I used to give my own child which went along with a funny voice and made him laugh a lot. I saw the name as something similar to something an auntie used to call me – Fish Face – silly and affectionate. It hadn’t occurred to me (here’s that blind spot), that as my friend pointed out, noses may be a feature that black children get teased about, so Natasha’s nickname was changed to Tashtastic. It’s a minute point in the story – does no harm changing it and avoids risk of upset. I’ve had conversations with people about creating who say “You’re bound to offend someone with your work so you may as well not worry about it.” or “This work isn’t for people who are easily offended.” Both of these are huge cop-outs, based on the assumption that the creator’s own personal sense of what is acceptable should be the measure to which other people’s own sense of the same should be measured. If you’re a straight, white male creator however, how can you possibly say what, for example, a lesbian person of colour should find acceptable, if you’re making a reference to being a lesbian or a person of colour?

I’ve had conversations with people about creating who say “You’re bound to offend someone with your work so you may as well not worry about it.” or “This work isn’t for people who are easily offended.” Both of these are huge cop-outs, based on the assumption that the creator’s own personal sense of what is acceptable should be the measure to which other people’s own sense of the same should be measured. If you’re a straight, white male creator however, how can you possibly say what, for example, a lesbian person of colour should find acceptable, if you’re making a reference to being a lesbian or a person of colour?

This doesn’t mean I want to create bland inoffensive work. The question is, if I am going to offend anyone, who is it I’m offending, and is there a point to why I’m doing it?

Back to my previous point of character diversity… do any of my future central characters have to be a straight, white male? Unless there’s a very specific reason, then I think the answer’s no. Having had one person of colour star in one of my works, and a girl (albeit an octopus) star in another, that doesn’t mean I can rest on my laurels as far as diversity is concerned. Like it or not, even if we create our work in a bubble, any piece of fiction we write that is published, is part of the huge lexicon of literature (or whatever narrative medium you create in), with an extremely disproportionate amount of straight, white, male leads. Creating one piece of work with a diverse protagonist doesn’t give moral licence to then go back to focusing solely on more typical lead characters.

I love Peter Parker and Harry Potter and Charlie Brown and heaps of other straight white male leads, but imagine all the equally amazing non-straight white male characters that could have become part of popular culture had it not been for the default protagonist type that creators gravitate towards.

Recently I heard comedic actress and writer Mindy Kaling chatting about how important it was for her sitcom character Mindy Lahiri (The Mindy Project) not to be defined by her ethnicity (sadly this was on YouTube, not in person, over coffee – I’m not that cool). She mentioned how a white actor like James Franco could be a complete blank slate when taking on a role. Minority actors have to take an audience through so many preconceived ideas before they can see what’s truly unique about the character they are playing.

Likewise, Eddie Murphy has discussed his time during the early eighties on the legendary American sketch comedy show, Saturday Night Live, explaining that being the sole black actor in a white cast had huge implications on the parts he played in the show. If he were to appear in bed with a white actress, the audience would assume that whatever comedy was to follow, would be based around the fact that he was a black man in a relationship with a white woman, rather than anything more unique or distinct about their situation. Likewise with his time on the same show, black comedian Chris Rock found himself largely being asked to make comedy about race. Once he moved on to his solo TV show (The Chris Rock Show) and stand up specials, only a small portion of his act was about his race – the majority was more universal.

Saturday Night Live has a long way to go in terms of diversity but at least now we are at a point where an interracial or single sex couple are not necessarily the source of comedy in a sketch.

I’d like to build on the idea of diverse characters being “everymen” and “blank slates” in my own work too. I’ve got a long way to go in my own range of characters – I need some transgender representation, more body type variation and even more leads wearing glasses. The bar is set so low for diversity at the moment – so there is much to learn. I hope my child will grow up to see my own lack of perception as narrow minded and help enlighten me.

I’d like to build on the idea of diverse characters being “everymen” and “blank slates” in my own work too. I’ve got a long way to go in my own range of characters – I need some transgender representation, more body type variation and even more leads wearing glasses. The bar is set so low for diversity at the moment – so there is much to learn. I hope my child will grow up to see my own lack of perception as narrow minded and help enlighten me.

Thanks to Lenna Cumberbatch

If you would like to read more posts like this and get the latest news and offers on our comics and graphic novels, why not join our mailing list? We can send information by email or post as you prefer.