Here, archaeologist and illustrator John Swogger answers some questions about his new graphic novel, Something Different About Dad: How to Live With Your Asperger’s Parent, co-authored with Autism Quality Development Advisor Kirsti Evans.

Here, archaeologist and illustrator John Swogger answers some questions about his new graphic novel, Something Different About Dad: How to Live With Your Asperger’s Parent, co-authored with Autism Quality Development Advisor Kirsti Evans.

It is unusual to tackle this subject with a graphic novel. How did this book come about, and why did you choose this format?

This project actually started out as something much smaller – a leaflet or small booklet. Kirsti had mentioned to me on several occasions that she was having trouble locating any suitable information to give to children whose parents were in the process of receiving a diagnosis of autism or Asperger Syndrome, as most of the literature was actually aimed the other way around – at parents whose children were receiving a diagnosis. As a result, she decided to produce a leaflet herself and asked if I would do some illustrations for it.

I was happy to do them and so we talked about what she wanted to have illustrated. Kirsti said that she would be writing the leaflet using a lot of vignettes and examples – “if your Dad does this”, and “when you Mum behaves like this” – that sort of text. She also she said that, as the leaflet was being aimed at children over a wide age range, it would be good to have some accessible, cartoon-y pictures to complement and parallel the examples.

As we talked, we ended up focusing on the idea of using the setting of a single family, as this would be less confusing for a child audience. At the same time, Kirsti was pulling together more and more examples of behaviours which a child might find confusing or need explanation, and the leaflet was rapidly evolving into a large booklet or even a book-length publication.

To be honest, I’m not sure who suggested the actual idea of dispensing with the text + illustration format and going for a completely graphic format, but as soon as the idea popped up, it became obvious that this was the best way to do it.

For starters, we knew that we wanted to be able to talk across as wide a “child” age-range as possible. As literacy skills develop both quickly and unevenly across the population, we realised we might have difficulty correctly pitching purely text-based explanations. We also knew that the issues we were wanting to address were very complex and that some of their inherent subtleties and nuances might be “flattened out” if we simplified the text down to a point where it was widely accessible.

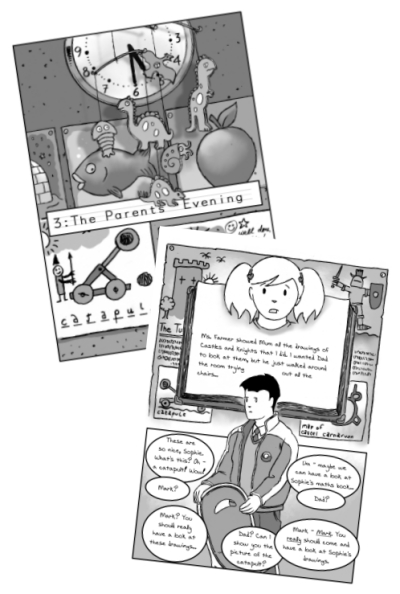

Reading a comic or graphic novel is not quite the same as reading a book with illustrations in it. In an illustrated book, the information you get via the text is supplemented by the information you get via the illustrations. But in a graphic novel or comic, you get access to information in three ways: (1) through the text, (2) through the pictures, and (3) through the combination of text and image. The story being told in the text is not just supplemented by the pictures; it actually joins with them to become a different kind of reading experience.

For example, in Something Different About Dad, there’s a scene where Mark – the father, who has Asperger Syndrome – is getting increasingly confused and stressed as the house fills up with family and friends on a busy and sociable Friday evening. If we were writing this scene in a story book or novel, we might describe how Mark became uncomfortable because he couldn’t follow all the various conversations, because he couldn’t follow what everyone was doing, and because there was a lot of subtle non-verbal interaction going on around him that left him isolated. If we were drawing a picture we could show the worried look on Mark’s face, the fact that he’s standing off by himself, and the crowded kitchen with lots of things happening at the same time.

But in a comic format we can bring all those elements together. In the comic version of this scene the pages are crowded with fragments of conversation, people dart from one panel to the next, their expressions and actions constantly changing. We can bring in the voices of the characters in the text, and then make the words themselves bigger or smaller, make the speech-bubbles overlapped and obscured to give a feeling of the fragmented nature of the conversation and the chaotic mix of sounds. And in amongst all of this is Mark, almost literally overwhelmed by everything else in the panels. This mixture allows you to tell a very dynamic story

How does the book reflect the experiences of children who have a parent with AS?

Something we chose to avoid early on was including anyone (other than ourselves as narrating characters) who had a professional understanding of the situation – nurses, doctors, counsellors, social workers or behavioural/mental health professionals.

Something we chose to avoid early on was including anyone (other than ourselves as narrating characters) who had a professional understanding of the situation – nurses, doctors, counsellors, social workers or behavioural/mental health professionals.

I think we felt that it was important to show that an understanding of Marks’ differences could genuinely come from the strong bonds of affection that the family already shared. Yes, that affection could be sorely tested – and we showed some of that – but it was still there, and formed the root of everyone’s desire to understand Mark’s AS more clearly.

In terms of describing how Mark’s Asperger Syndrome affected his daughter Sophie’s understanding AS, I think both Kirsti and I felt it was important to have Sophie’s experiences be the main focus of the narrative. By that I mean that we didn’t want to stray too much into areas of Mark’s life that Sophie wouldn’t have really seen or experienced.

For example, although we touch briefly on the difficulties that Mark must experience at work – we see Mark being isolated from his colleagues’ social interactions and conversations – we cut a scene in which Mark’s wife Vicky talks about how Mark’s obsession with time-keeping causes friction between him and his work colleagues; it was more relevant to Sophie’s experience of her Dad’s AS to bring that into the Parent’s Evening chapter.

As a result of these decisions, I think there was a fairly significant issue we chose not to address head-on, which was: how was Mark’s AS identified in the first place? In early drafts, we had Vicky – who works at a hospital – overhear a conversation which described someone diagnosed with AS, and as a result she suddenly realised that this conversation might have been about Mark. Vicky talks to a professional and gets some information in the form of leaflets. In the end, we decided to drop this particular scenario as it was a scenario that Sophie herself would never have seen or necessarily fully understood. We thought it would be much better if Sophie’s understanding of AS evolved not out of the events surrounding a formal diagnosis or identification, but out of a vague feeling that somehow her Dad was “different”. We felt that this was a process which might more accurately reflect the experiences of most children in similar situations.

At what age do you think children can be introduced to a resource such as your book?

Six, seven, eight – this is probably the age when children generally start to become really aware of the differences between themselves and other children, and between their families and other families. We made Sophie eight-ish. She’s at that age when sameness and difference starts to become important. She likes certain things, and uses them to create an identity for herself. I suppose this marks the bottom end of the target age group we had in mind.

But one of the great things about the comic/graphic novel medium is that a much younger audience can engage with the story without having to necessarily be able to read or understand the text. My Dad was a great linguist, and used to practise his conversational skills by reading comic books in foreign languages. My first experience of reading comics was Asterix and the Goths – in German, and Tintin and the Blue Lotus – in French! Not knowing a word of German or French didn’t make much difference to my ability to understand the story. Years later, re-reading those books in English, I was really surprised how complete an understanding of the story I’d picked up just by looking at the artwork. The same thing will hold true of English-language comics that are beyond the literacy skills of the reader – at least some of the story can be picked up through the artwork alone.

And here’s another great thing about comics and graphic narratives: like any story book with pictures, they have the ability to become interactive. Most children’s first exposure to books is through a story book with pictures being read to them. They can share in the work – and the reward – of unfolding the story: they do their part and “read” the story in the pictures while the older/more grown-up reader reads the story in the words. Something Different About Dad could be used with much younger children if a parent or older reader like this – the younger child “reading” the pictures and the older reader reading the text. Kirsti and I both thought that this might be a good opportunity for both grown-ups and children to share the learning experience during what might be a very unsettling time for everyone.

How do you hope your book will help families in which a parent has AS?

I’d like to think that, as I’ve suggested above, parents and children could use the book together to share the experience of learning about AS. I’d also like to think that the use of the graphic novel format helped to create a learning experience that wasn’t intimidating. Finding out about something as important and life-changing as your parent’s AS has the potential to overwhelm. When my father was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s ten years ago, even I – an adult used to reading obtuse scholarly archaeology texts – found the density of information and specialised language of even basic informative texts really off-putting and very intimidating. I think using comics and graphic formats when talking about things to do with behaviour, health or illness can help integrate the very dense, sometimes technical and “clinical” information into the practical, emotional and deeply personal side of the issues.

Copyright © Jessica Kingsley Publishers 2011.