Here, Jonathan Shailor interviews Brent Buell, one of the contributing authors to his book, Performing New Lives: Prison Theatre, which draws together some of the most original and innovative programs in contemporary prison theatre.

Brent is well-established New York City actor, writer, director, producer, filmmaker and social activist, and is the author of Chapter 3: Rehabilitation Through the Arts at Sing Sing: Drama in the Big House.

Jonathan: Let’s start at the beginning. How did you become involved in prison theatre? What has this experience meant to you?

Brent: A friend of mine was teaching GED (General Education Diploma) courses at Riker’s Island (a huge New York City prison) and his enthusiasm was infectious. I was hoping to find a way to use my acting and theater background in a prison setting. Then by chance I met Dr. Lorraine Moller and she told me about a prison theater program at Sing Sing Correctional Facility (located in New York State) called Rehabilitation Through the Arts. I met with the program director, Katherine Vockins, did my volunteer orientation, and the rest as they say is history.

I love theater. I think that it is one of the most powerful forces for social change that exists. For ten years I’ve witnessed how magnificently theater—just theater, no therapy, no sociodrama, no psychological agendas—can touch and renew the human spirit. It’s the greatest single gift my art has given me. I am sure that other approaches have their place, but for me the process of theater is all that is needed to touch and begin to transform anyone.

We all spend much of our lives building up defenses against an unfriendly world, an uncomprehending universe. That surely is true of the men I met and taught in prison. They were like me. They were tough guys hoping that someone somewhere could reach that almost-forgotten part of them, break it loose, set it free and let them feel human again. After all, to portray a character is to find that character’s heart—and in the process to find your own. To direct a play is to think what would bring the best out of an actor—and in the process to find the satisfaction of hoping for other people to be better through knowing you. To study a play is to find the arc, the direction, the meaning of a story—and in the process to see that your own life has an arc, and that the direction is in your own hands.

My hours in prison were the ultimate validation that I was right to choose theater for my profession.

Jonathan: Tell us about your chapter in Performing New Lives – what is it about, and why did you choose this focus?

Brent: Rehabilitation Through the Arts is the theater program that functions at Sing Sing and a number of other facilities (in addition to Sing Sing, I also worked with RTA at Woodbourne, Greenhaven, and Fishkill Correctional Facilities). Thanks to Warner Brothers movies, Sing Sing became known as “The Big House.” It’s the place about which the phrase “up the river” was coined. It has housed some of America’s most “famous” prisoners. It is the location of the infamous Death House where Julius and Ethel Rosenberg and 612 other people were executed in the electric chair that was grimly nicknamed “Old Sparky.” So, to point to drama in that big house—drama of a wonderful, positive and life-changing kind—seemed the right choice of title.

My focus was personal. It was about my experience as a volunteer and how while watching theater change others, I myself was changed.

Jonathan: Can you tell us about your latest production, and how it relates to your commitment to the arts and activism?

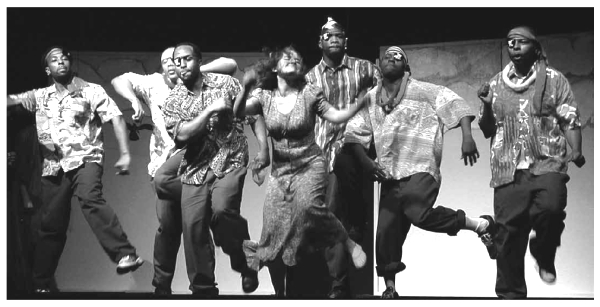

Brent: Yes, I’m directing and co-producing “unFRAMED,” a one-man play written and performed by Iyaba Ibo Mandingo. It is about Iyaba’s journey from an idyllic childhood in Antigua to life as an outsider—an undocumented immigrant—in the United States. It is about love, race, family and politics—all told through a mixture of stories and Mr. Mandingo’s amazing poetry. It culminates with the true account of how, after 9/11, Iyaba was arrested and scheduled for deportation because of his political poetry—poetry which, I am proud to say, is in the show. In the course of the show he also paints a self-portrait!

My relation with the show is directly tied to my work in prison. It’s such a good story I’ll relate it quickly here. The first production I worked on inside Sing Sing was a stage adaptation of Richard Stratton’s film, “Slam”, about a young slam poet who is incarcerated in the Washington D.C. county jail. The producer brought in one of the nation’s top slam poets to teach the leading man (a prisoner) how to do true slamming. Well, that top poet was Iyaba Ibo Mandingo. The first thing he did was his poem “41 Times” about the murder of Amadou Diallo by the New York City police. I was moved to my center by the poem and doubly so because I was very involved in the protests of that murder. When we were leaving the prison that night Iyaba turned to me and said, “One day I’m going to write a play about my life, and you are going to direct it.” Nearly ten years later he called me and said, “Remember the play I told you about that night at Sing Sing? It’s ready. Come up to Harlem and see it.” I did, and our journey began.

We did an industry performance last June at Playwrights Horizons, and TONY Award-winning Broadway producer Jane Dubin was in the audience, loved the play, and has optioned it for a New York production. We are currently on an out-of-town tour and plan to be in Manhattan by the end of the year.

I see the purpose of this show as a parallel journey with my work inside prisons. Its message is so direct, so hopeful, and so in tune with life in America at this moment. It educates audiences on the currency of subjects that many of us would like to think are in the past. The very popular myth that we are in a “post-racial society” is one of them. We are including talkbacks and presentations for young people—and because of Iyaba’s extraordinary ability to speak to the issues that so concern them, I know that this show will stop some young people from having a life of incarceration. It’s that powerful.

Jonathan: Who do you hope will read the book and your chapter? What do you hope they will take away from it?

Brent: While I hope that Performing New Lives has wide circulation with people who have an interest in prison theater, I have even a larger hope that it will be read by people who have had nothing to do with corrections or incarceration. The misconceptions of who we have locked up in our nation’s prisons are mammoth. It’s so easy to think of men behind bars as “them,” and quickly assume that a violent, animalistic nature is pervasive. Our book will put the lie to that easy, corrupt notion.

The chapters in this book by my colleagues are the real story. People behind bars are just like us. Many have made terrible mistakes, done terrible things—but they are still human beings, struggling to maintain that humanity inside a system that is designed to erase one’s humanity. Because they exist in that atmosphere, because they endure strip searches, endless orders, deafening noise, lack of privacy, and numbing boredom—I have found that there is a level of self-questioning inside prisons that is unusually high. I am always pleased that as I’d come in and greet the men in the program that the first questions weren’t “How about them Mets?” or some other sports or small-talk subject. The questions were about life, about meaning, about thought. I remember one man who had taught himself to read while in prison. I saw him with a book one day and asked what he was reading. “This guy Hegel,” he said, “I’m studying him in relation to the development of religious ideas here and in Africa over the last two-hundred years.” What’s not to love about an answer like that?

Discovery. That’s what this book is about. The reader will discover himself or herself in a world that they have largely imagined through the lens of movies and TV as a zoo where daily life consists of murder plots. They will discover a world of people learning, growing and changing through the education that begins with theater.

Once a person finds that theatrical literature is a gateway to places and ideas that were never a part of growing-up life (most prisoners have never seen a live stage play), the desire to learn more is the inevitable follow-up. I watched men who had spurned education decide to enroll in a GED program, then matriculate to college, and then go on to get their Master’s degrees. Wow. That’s what’s in the pages of Performing New Lives. Step right up and buy this book!

While I’m on the subject of this book, I’d like to say something about my co-authors. You, Jonathan, enabled us to form an online community that gave us the chance to meet one another even though we were spread across the country. What a privilege! I so respect each of the contributors to this book because they are doing some of the most beautiful, life-changing work that anyone could undertake. And they are doing it without an agenda. That is what has affected me so much. They are doing it because they love the people they serve and know that lives can be turned around and made whole. The lack of ego and competitiveness has particularly impressed me, and I have come to love these artists—even though I have yet to meet most of them in person. Even via email you know when your life has come into contact with honest treasure. Thank you so much for being a means of this happening.

For more info about Brent and his upcoming projects, visit www.BrentBuell.com. To learn more about unFRAMED, visit www.unFRAMEDthePlay.com.

Copyright © Jessica Kingsley Publishers 2011.