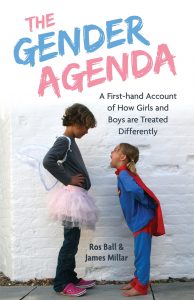

Authors Ros Ball and James Millar co-run the popular Twitter account @GenderDiary, which they set up in 2011 to record all the ways their young son and daughter were treated differently by friends, family and even strangers in the street. Adapted from the account, their new book, The Gender Agenda, explores how this inherent gendering can affect the formation of children’s identities and provides gender non-specific resources for parents keen to challenge the stereotypical status quo. We caught up with Ros and James for a chat, ahead of the book’s release.

We wouldn’t have The Gender Agenda without the @GenderDiary Twitter account, which chronicles the everyday examples of gendering that you encountered while raising your young son and daughter. What was it that triggered you to set up the @GenderDiary account in the first place?

When our son was born, nearly three years after we had a daughter we picked up that they were being treated differently in little ways. Not just the obvious pink cards and blue cards but the presents we received for them when they were born – our daughter was given a little fluffy white bear in a pink hat, our son received a green dinosaur baring its teeth. The subliminal message from the off was that aggression is for boys.

We were both paid up feminists long before we even met, hence James was reading Living Dolls by Natascha Walter, which was the big feminist book at the time, and that was the trigger for the project in that it mentioned ‘There’s a Good Girl’ – a 1981 book by German lawyer Marianne Grabrucker. James tracked down a copy on eBay and gave it to Ros for Christmas (probably the best present he’s ever given her in nearly 20 years.) Ros read ‘There’s a Good Girl’ and was totally overwhelmed by a feeling of “YES. This is how I feel. This explains so much of my ANGER.” It then seemed a really natural outlet to start writing it down, and since we were both fairly avid fans of Twitter already that seemed the obvious place to put it as you could share your thoughts, experiences and feelings fairly instantaneously and, as we were to discover, get feedback too.

You co-run the account, but tweet anonymously. Why?

Fairly early on in the project we asked our followers whether we should say who was tweeting and the general consensus was no. While it might be interesting to compare the different attitudes that we bring to the issue it’s actually more interesting to strip away the preconceptions that readers bring. Many readers have told us that they might read an entry thinking it was Ros that wrote it only to discover, perhaps due to a reply or a tweet further on, that it was actually James. It showed that even just reading 140 characters people project so much and try to gender things.

The other happy by-product of tweeting anonymously – or at least not letting on which of us was tweeting at any given point – was that we were never bothered by trolls much. Unfortunately, we’re fairly sure that if we had said who was tweeting Ros would’ve faced a fair bit of online abuse. James might have too but it would have been a different kind and probably a different magnitude.

What has been the most surprising discovery you’ve made while running the account?

Two things: first that we are part of the gender police. It’s not like we started thinking we were so much better than everyone else! But we did think we were pretty good feminists. Turned out even within paid up feminists such as ourselves ingrained attitudes run deep and we would think twice, or check ourselves before dressing our baby son in one of his sister’s old dress tops for example, even if he was wearing it under dungarees!

The other thing was how much boys are impacted by gender stereotypes. As feminists, we started out thinking that women are obviously the ones who need to break the patriarchy. But we ended realising that the patriarchy and the toxic masculinity it feeds off are really bad for boys too. Clearly the impacts are different but we weren’t as aware of the way boys are taught to be aggressive from the off and to have such disdain for things connected to the female sphere such as empathy and childcare.

You have a big following on Twitter, and many of the interactions you’ve had with other Twitter accounts are included in the book. What has been your experience of sharing your findings on Twitter? Was there any negativity?

Very little negativity. We started the diary on Twitter just as a way of documenting the things that we observed. We didn’t really expect to find such a vibrant community online that almost immediately offered support and co-operation. It was great. And it led to a number of real life meetings which were even more satisfying. For example, we’ve continued to work with and get to know the team behind Let Toys be Toys.

As mentioned above and having seen some of the unpleasantness that some accounts have to put up with we’re quite convinced that not saying whether it was the man or woman that was posting has helped to keep some of the worst misogynists at bay.

The book isn’t about gender-neutral parenting, but about how we can be more aware of the gender policing that happens around us (and from us, albeit usually unwittingly) and how this affects how children form their identities. How has the project affected how you raise your children?

It certainly made us more aware of our own shortcomings, which is no bad thing. And it made us think about our own upbringings and the attitudes we picked up growing up. It probably affected how we divide the childcare. Initially Ros took on the bulk of it just because we were fitting in with the norm. But as the project rolled on it became clear that we should model the alternative ourselves so we changed things around and James became the primary child-carer which just worked better for everyone.

It made us aware of how much gendering goes on in society. We didn’t expect to have so much material to tweet and put in the book. And that’s probably the most important thing, that it’s not just about our kids, the impact is on all children and that’s what drove us to keep it up and ultimately publish our findings because we want as many people as possible to think about the gender police.

And beyond being parents, do you think it has filtered into your other relationships – with friends, family and colleagues?

Inevitably we’ve talked a lot about the topic with friends and family. Although they don’t always agree with our point of view everyone is incredibly supportive and backing the book to succeed.

There’s examples in the book of how hard it can be to challenge friends and family that we think are perpetuate stereotypes. With friends it can be tricky because how someone parents their children is quite fundamental to their identity so that has to be approached with care. With family it’s slightly different because they can’t drop you! And we found that as we kept going on about the issue they did alter their behaviour and their language so there’s something to be said for perseverance.

One of the recurrent themes of the book is how children’s toys are dictated by gender. To combat this, you’ve collated lists of children’s books and films that challenge gender stereotypes for the book. Was it difficult to find these resources?

The evidence all shows that there are fewer books and films with female leads and representation remains poor. But the hive mind proved brilliantly effective when it came to drawing up the resources in the book. With social media putting us in touch with so many campaigners and creators we were able to crowd source the lists fairly easily. And we always set out to be positive, to offer alternatives to people who don’t want to just accept the male-dominated culture whether that’s films or TV or books or toys that are handed to them. So, we were very keen that the book list and film list were available in the book to share with other people who either start the book looking for those sorts of resources or who read it and are inspired by the end of it to do so!

You started the Gender Diary in 2011. Over the past 6 years, have you noticed a shift in how people are responding to gender and the roles boys and girls (and men and women in fact) ‘should’ and ‘shouldn’t’ play?

It’s undoubtedly become a more mainstream subject in that time. We had to go looking on eBay for Marianne’s book from 1981, now there’s loads of books around the same subject. And of course, lots of resources online. In the time since we started activism that has popped up includes work by Girl Guiding, Sport England pouring money into the This Girl Can campaign, and the incredible Malala Yousafzai’s Malala Fund. We noted the attempted murder of a girl in Pakistan towards the end of the diary, and in the time since, Malala has become a global phenomenon and inspiration to us all.

Meanwhile feminism in popular culture has also changed. There is a lot less shuffling of feet when people describe themselves as one. In 2014 Beyoncé broadcast to millions with the word FEMINIST emblazoned in 10 foot high letters behind her. In 2017, millions marched in defense of women’s rights the day after Donald Trump was inaugurated. Not all would identify as feminists, they certainly looked like feminists on that unprecedented day of action and display of courage, strength and determination.

The flip side to that has been the rise of the ‘meninists’ – often boors and misogynists looking for respectability under the men’s rights banner. They are very silly people but their emergence is almost confirmation that folk like us are doing something right, that defined gender roles are being broken down. That’s confusing to the simpletons in the men’s rights movement but it’s good news for everyone else who wants to do away with the limits stereotypes place on boys and girls, and men and women.

And as the kids have grown older, are they subject to the same levels of gendering? Do people respond to their behaviour and likes/dislikes in the same way as when they were little?

They are still subject to gendering, school is a big influence in that. But we’ve made a conscious decision as they’ve grown not to focus on them so much. They are old enough now to make their own decisions. We’ve suggested to them that maybe when they are teenagers we could all work together on a second volume of the diary which would be a fascinating and possibly terrifying look at the gendering that kicks in at adolescence. They are keen and so are we but for now that’s a few years in the future.

Finally, what do you hope readers will take away from the book?

How simple and small things build up to direct children towards certain behaviours and attitudes, and how that puts limits on kids’ outlook, experience and future.

To consider their own behaviour, we’re not looking to be critical of anyone, we want to help people to see what’s going on and together we can change it for the better.

Follow Ros and James on Twitter @GenderDiary.

For more information and to buy a copy of the book, follow this link.

Why no join our mailing list for more updates on new books and exclusive content from our authors, or follow us on Facebook.