Beth Powell, LCSW, is owner of Beth Powell’s In-Family Services, an outpatient psychotherapy private practice specializing in trauma informed care. Her new book, Fun Games and Physical Activities to Help Heal Children Who Hurt publishes this month.

Bye-Bye Baby Bunting.

Daddy’s gone a hunting.

To catch a little rabbit skin,

To wrap his Baby Bunting in.

Mother Goose

When I was a small child being cared for by my aunt, she sang this song while rocking me to a slow 60-beat-a-minute rhythm. My aunt took over my care when my mother’s mental illness made it unsafe for my sister and me to be with her. What a contrast in care! My aunt’s rhythm, voice, words, touch, and smell were so much more soothing than my mother’s. With my aunt, I could relax. I didn’t have to struggle to get away or dissociate into a floppy, non‑moving, barely breathing, pretending-to-be-dead little girl. My aunt exuded safety and calm that soothed my restlessness.

Resting against my aunt’s chest, I felt the slow, consistent beat of her heart. I relaxed into the protection of her arms wrapped gently around me. Her voice, vibrating from her chest into my ears, awakened the proprioceptive neural impulses in my face that told me where I was in time and in space. Grounding me with her body, she held me so I wouldn’t fall. Wrapped in her loving arms, I felt safe enough to close my eyes. The sweet smell of my aunt’s skin pleasured the lower, emotional center of my brain, enticing me to lie close and be still just a little bit longer.

The more my caregiver sang and rocked me, the more her song and her rhythm calmed and relaxed her. As she calmed and relaxed, so did I. We shared a pleasurable experience. We connected in a happy, healing way. My receptive language was developing. Her words and touch assured me that there was someone much bigger and stronger than I was who had my best interests at heart. She was unafraid and confident in her ability to nurture. She put me first. By her loving actions, she was forming a template in my brain of safety–security–protection–trust in a higher power through a concrete, much-bigger-than-myself human being. The safety and security I felt in her arms paved the way for my future belief and faith in a loving, abstract, not-of-this-earth higher, heavenly power.

Adults create healthy, secure attachment in children through positive “real” non-virtual, physical interaction with them. Caregivers are able to instill in children safety–security–protection–trust because loving, protective adults instilled it in them. My birth mother couldn’t instill that in me. But my aunt and uncle, my grandma, and my first‑grade teacher, Miss Beetles, could. They were the human caregiving angels God sent my way. Thus, in spite of the hard beginnings I had, the template was established, in childhood, for the “me” I am today because of caregivers like them who somehow understood what I needed and were able to provide it when I needed it.

Internalized safety–security–protection–trust is the base from which self-esteem, self-confidence, self-responsibility, self-strength, and altruism develop. It is the support upon which mature character or the internalized Fruit of the Spirit must build. Without an internalized secure base, children develop anxiety and self-deception. When a child has a secure base in childhood with positive attachment to a preferred, stable, protective, and physically present primary caregiver, then a healthy relationship with God, whom we cannot see, is much easier.

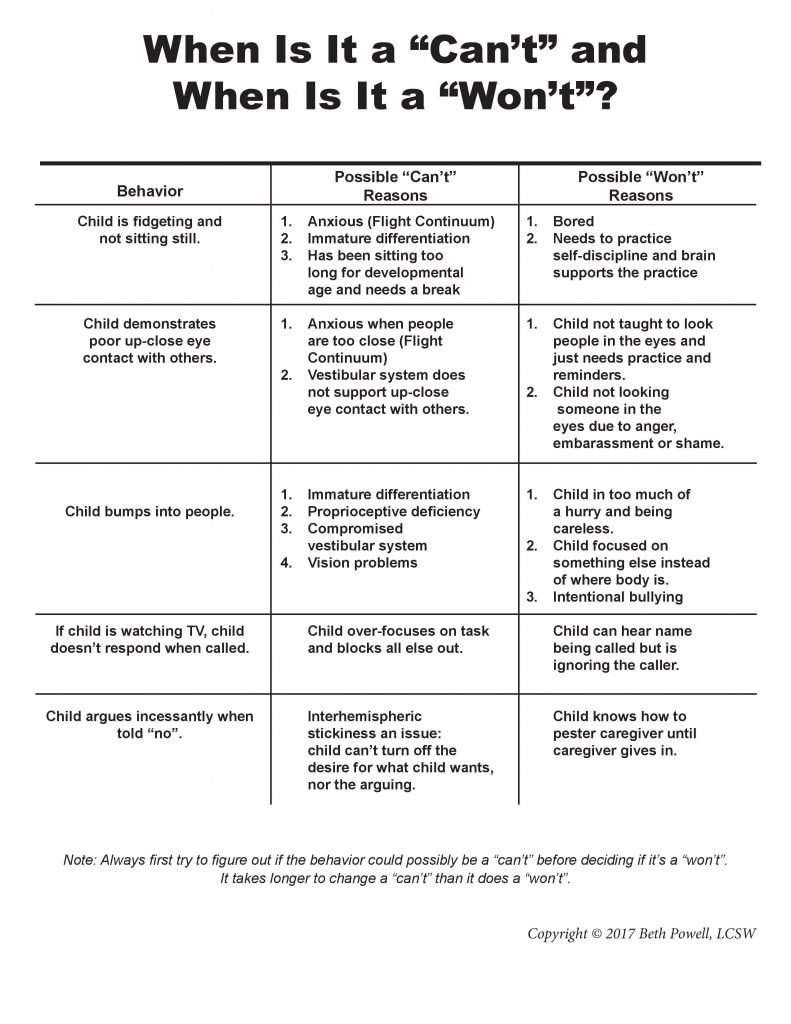

Insecurely attached and developmentally traumatized children often succumb to unhealthy control, anxiety, mistrust of those who love them, and abusive behaviors. As adults they either become their own God (unhealthy narcissism) or they may find God in substances or toxic behaviors. Reversing unhealthy belief systems is difficult but not impossible. It’s work that is definitely not for the faint of heart, nor for parents who take a child’s antics personally, as if it is “them” whom the child is out to get by interpreting their“can’ts” as “won’ts.”

Therapeutic caregivers of hurting children seek the sources of the unpleasant symptoms that they see, and they address those sources from a psychological, neuro-behavioral, socio-emotional and spiritual growth perspective. Children need to trust that adult caregivers can and will protect them. This trumps any other socio-emotional need in childhood. This is the base upon which the quality of the relationship with self, with others, and with God is built. A child who has experienced significant neglect, abuse, loss, and chronic and acute stress has an even greater need for safety-security-protection-trust experiences with loving, mature, and stable adults. They have a harder time developing trust because it has been broken, sometimes again and again.

Below is a therapeutic activity that caregivers can share and enjoy with the children in their care to help them establish an essential base of safety–security–protection–trust.

Caregiver–child rocking chair time to help calm brain and body

It’s not just about rocking infants any more. Larger children who hurt can benefit from rocking, too. And so can the caregiver. This comforting act helps regulate children when they are fretting and need help regulating themselves.

It also provides caregiver–child quality “love and bonding” time. How comforting rocking feels for both parties involved. Caregivers can even rock themselves when they feel out of sorts, and it helps to re-set their brain.

Rocking caregivers should add a slowly-sung comforting song, hum something spiritually soothing, or just gently make a “shush” sound with their lips and tongue while taking slow, long, and deep breaths to not only better regulate themselves but to give the child something to match. A regulated parent helps regulate a child. The drawn out “shush” sound and the slow, rhythmic rocking replicates the sound and the movement the gestational infant at least should have received in utero. This movement and sound helps the baby’s lower brain develop in a healthier way to better manage stress. It also helps the older brain do the same.

Caregiver-initiated knee-bouncing games to help install rhythmic synchronicity and nurture trust in children

One of my favorite close times with the adults who loved and enjoyed me as a child was to “Go See Mr. Brown.” I’m not sure where this knee-bouncing game originated, but it could have been passed down generationally through my South Mississippi maternal ancestors.

To perform this adult-activated activity, the child first sits, facing the adult, on the adult’s knees. It’s important that the adult’s face and body language convey confidence and fun with lots of facial expression and eye contact.

The adult securely holds onto the child while the child securely holds onto the adult. Then the adult bounces the child slowly and consistently up and down on the knees in synchrony with the words and the 60-beat-a-minute rhythm of the following song:

Mr. Brown went to town

Riding a goat and leading a hound.

The hound barked; the goat jumped.

Threw Mr. Brown right down on a stump!

Surprise! The child does not tumble onto the floor. Instead, the adult gently, slowly, and securely tilts the child backward as far as the child can comfortably tolerate without showing signs of anxiety and fear. Then slowly, the adult returns the child to a sitting position on top of the knees. The adult then asks the child, “Who kept you from falling on that stump?” “You did!” is the desired answer. “And I will every time!” can be the adult response.

As the child grows in trust that the adult performing the activity will keep him safe from falling, and will stop if the activity scares him, then the adult may gradually increase the speed and the depth to which the child is tilted back. In the situation of a hyper-vestibular child (child fearful of too much movement), that may not be by much because the part of the brain which reads and adjusts to movement isn’t working as optimally as it should. Heed the expression on the child’s face and take notice of resistance in the body to the tilting back movement. Ask children if they are ready to tilt back. Don’t force a child to tilt back farther than he or she is ready to go. That doesn’t build safety-security-protection-trust.

“Lap therapy” time is supposed to be pleasurable and bonding. It should be mutually enjoyable with lots of eye contact and joyful, loving facial expression on the part of the caregiver!