200 Tricky Spellings in Cartoons author Lidia Stanton discusses the upcoming book and how it can help parents and teachers teach spelling in a way that sticks.

Can you briefly outline your history working with kids and teens? How has this background influenced what you write about?

I’ve been a Special Educational Needs (SEN) specialist since 2004, working as a dyslexia tutor and assessor. In 2015, I gained a postgraduate qualification in psychology, which gave me the confidence to work with children and teens with ADHD and ASD. Prior to the current COVID-19 quarantine, I would see children and teens in a local clinic, in schools or in my home office. You’d also find me with parents and their kids with dyslexia or attentional difficulties in parks, where we’d practise reading and spelling in sand or mud, doing numberwork with pebbles and sticks, or practicing times tables on our hands while marching on the spot.

I’ve always been partial to multisensory teaching strategies because you see their results so quickly and they are so much fun. But I also deliver phonological reading and spelling programs in a more cumulative manner over months, sometimes years, rather than weeks. My proudest professional moments include weaning kids off my direct support. It’s a wonderful feeling knowing that they have found a way of working with literacy or numeracy that makes perfect sense to them.

I only write books when I’ve got something to share with families of SEN children, the children themselves and their teachers. The ideas come straight from my work; I only need to rummage in my notes and lesson plans.

What can kids learn from 200 Tricky Spellings in Cartoons?

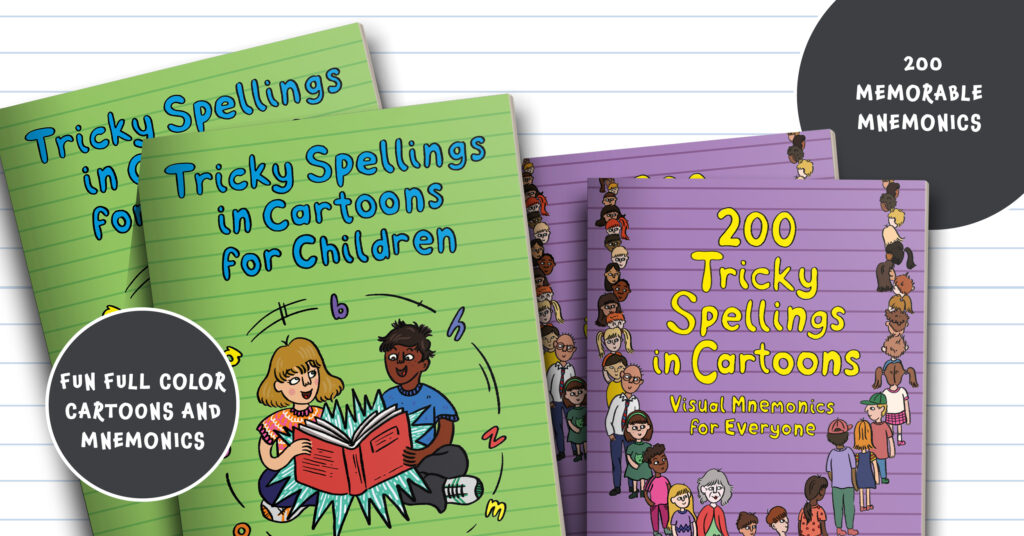

The book is for anyone over the age of 7 years old, but particularly for older kids, teenagers and adults (there is a younger-age book equivalent Tricky Spellings in Cartoons for Children specifically tailored for budding readers and spellers). It shows how to learn to spell (in no time at all) just over 200 of the hardest to learn confusing homophones and irregular spellings in English. It does this by drawing attention to hidden stories within the words that can be visually illustrated and maybe even acted out to remember the spelling better.

This learning method is called mnemonics (pronounced with a silent frontal /m/). Mnemonics work by stimulating imagination; using words and other tools, they encourage the brain to make associations. This provides for a refined way of accessing the information stored in the brain in the correct order. Mnemonics are particularly helpful for kids with dyslexia, as traditional auditory learning methods are not effective for them.

Very many grown-ups, not only kids and teens, have found the book entertaining and educational in equal measure. Grandparents tell me they have learned mnemonics from the book to be able to help their grandchildren with spelling and share fun times together.

How can 200 Tricky Spellings in Cartoons be used in a classroom or other school setting?

I know schools that have adopted the book as an alternative spelling dictionary in the classroom; they also have copies in the school library. Although teachers have always enjoyed using spelling mnemonics in the classroom, there had not been a spelling dictionary with so many of them in one place. Some teachers use the book as and when needed; others incorporate it into their lesson plans when introducing new lists of spellings.

With a lot of students home and many parents experiencing the difficulties of home schooling for the first time, how can 200 Tricky Spellings in Cartoons help support both kids and parents?

Think of the book (and its younger-age equivalent Tricky Spellings in Cartoons for Children) as a learning ‘conversation starter’. With the child, find the tricky words you’re planning to teach and examine individual cartoons, making sure the connection between the spelling and the story makes good sense to the child. Make this time as relaxing, enjoyable and memorable to the child as possible by acting the story out, perhaps adding a funny situational context that is personal to you and the child.

“Focus on action and play while combining as many senses as possible during learning: use pretend play to act out stories and situations, encourage visualization, and experiment with fun voices.”

After that, it’s time for learning consolidation (making sure the learning ‘sticks’) using multisensory strategies that involve body movement. This part feels like play rather than learning, which makes the book particularly attractive to kids! Focus on action and play while combining as many senses as possible during learning: use pretend play to act out stories and situations, encourage visualization, and experiment with fun voices. Always focus on the ‘tricky’ part of the word: How did you remember it?

Ask the child to write the word on the refrigerator, windows, and glass sliding doors using a wipeable marker, on the sidewalk using colored chalk, on the ground or fence using a squirty water bottle, in shaving cream on the table, or spread the shaving cream on the surface so the child can use their finger to write the word, in a baking tray filled with a shallow layer of salt or flour using their finger or a wooden spoon. Help the child to mold the word out of putty or dough, make the word out of small building blocks, bake the letters out of pastry or cookie dough, arrange them in the right order, and then enjoy eating the word. Encourage the child to recall the spelling mnemonic while bouncing on a trampoline, say the tricky part of the word in a funny or singing voice, or draw a picture/make a poster with the word and display at home or school. Finally, the best way to learn is to teach: ask the child to teach tricky spellings to other family members and their friends.

What was your initial inspiration for 200 Tricky Spellings in Cartoons?

At some point, I was working with a group of dyslexic teacher training students revising for their Literacy Skills test with a spelling component that was really hard to pass. We decided only mnemonics would make the spellings stick: pictures, stories and sayings that worked as memory triggers. If there was a mnemonic that already existed, for example There’s a rat in separate, we used it. If there wasn’t, we looked for personal connections between the word and the student, for example When I think of research, I imagine a sea of papers. Unless I start reading, I’ll drown in the research project.

As it turned out, a lot of the mnemonics were actually quite clever, sharp and catchy. I kept a record of all them and recycled them with new students every year. At some point, I had so many, I thought I had to share them with as many kids and grown-ups as possible by putting them in a book.

In the past couple years, so much research has been done on neurodiversity and how kids learn differently. What are small steps teachers and educators can take to ensure all kids are getting the best out of their school day?

No two kids will learn in the same way, but any kid will learn in no time when the material is fun and relevant to them. Play and humour is key to make learning stick. Humour triggers our brain’s reward system by releasing dopamine, and dopamine increases our motivation. When we are motivated, we find learning enjoyable. When learning is enjoyable because it’s fun, it becomes memorable because the information (how to spell the word) ends up in the long-term memory networks in our brain. And so, humour is a natural tool to increase learners’ retention of spellings.

When something is funny or intriguing, it creates a sense of wonder, a feeling that something is possible, that we can do it. Silliness is also a great learning tool. When we are silly, our bodies and our brains relax, and any anxiety goes away. The kid is more likely to look at a hard spelling if the story around it is silly in an appealing way so they can’t help but think about it.

With all the stress about COVID-19 at the moment, what are some ways we can help young people with dyslexia and other learning differences?

Do whatever feels right and makes sense to the child. Be guided by them and take note of what works for them. If they manage to learn 10 spellings while jumping on a trampoline, celebrate it, but don’t ask them to sit at a desk and learn the next 10 spellings by copying them out from a book. Look for patterns that will tell you how your child learns. If they enjoy learning on the go, check out my comic book I Learn by Doing for more practical ideas. It is sometimes the simplest things that really work: silliness, humour, action, movement, free play, yet we don’t consider them proper learning tools. Don’t feel your child has to learn the way other kids do. Don’t compare your family against other home schoolers, and never feel that you have to explain yourself to anyone. Find the comfort in the progress your child is making.

Are there any other resources you would recommend?

You will find neurodiversity-friendly learning resources by typing ‘multisensory’ in online bookshops’ search windows. One of them will be my favourite resource The Big Book of Dyslexia Activities for Kids and Teens by Gavin Reid, Nick Guise and Jennie Guise. It’s packed with fun multisensory activities for learning English at home.

If you’ve enjoyed my spelling books, you might look for my other titles by visiting the JKP website or my own website where I’ve listed the books I had self-published prior to collaborating with JKP.