Hello there!

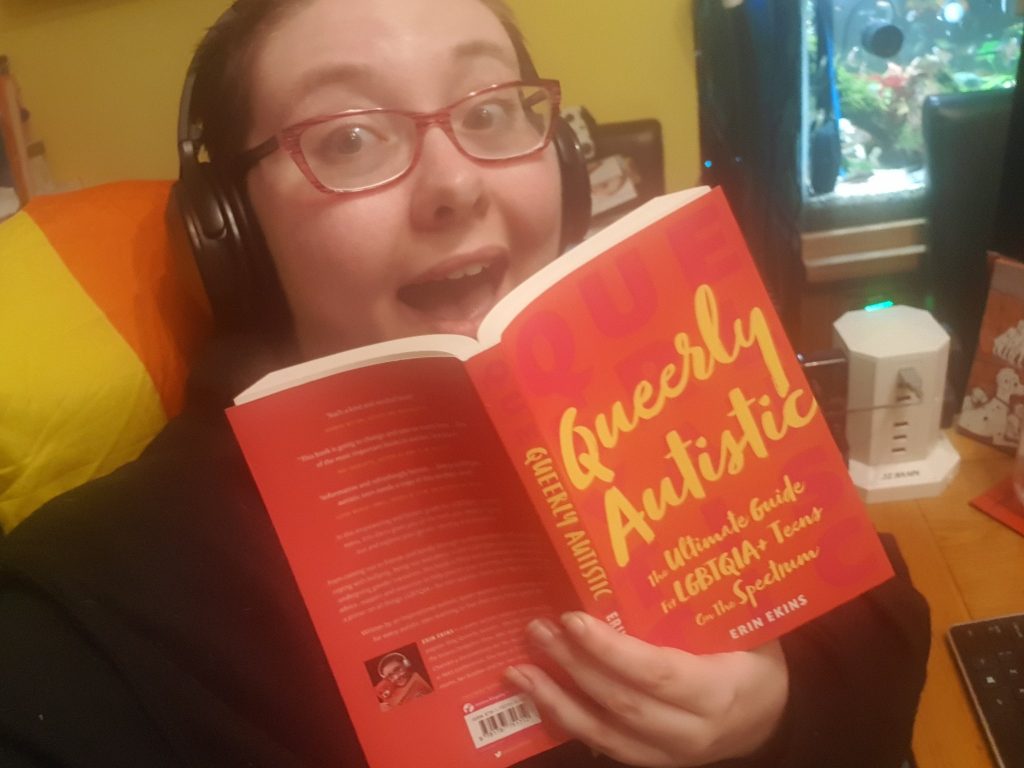

My name is Erin. On the internet, I am also known as Queerly Autistic.

This is because I am queer. And I am autistic. I like to say that I live under the double rainbow. But what is the double rainbow?

The LGBTQIA+ (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer/questioning, intersex, asexual, and other non-straight, non-cisgender identities) community is represented by the rainbow flag. Designed by Gilbert Baker in 1978, at the request of famous gay politician Harvey Milk, the rainbow was a symbol for San Francisco Pride. It has since spread as a symbol for the LGBTQIA+ community across the world – the different colours of the rainbow capturing the different people and identities who live under it.

We also know that autism is described as a spectrum. I was personally diagnosed with ‘autism spectrum disorder’.

Autistic people are often referred to as being ‘on the spectrum’. This is because it’s a wide range of behaviours and experiences grouped together. Not all autistic people have the same traits, but we often share similarities. The word ‘spectrum’, however, was initially a scientific term, meaning the rainbow of colours in visible light. This is why autistic LGBTQIA+ people are sometimes referred to as existing under the ‘double rainbow’.

This term exists because of one reason: a greater percentage of the autistic population identifies as LGBTQIA+ than the non-autistic (neurotypical) population. There have been a number of studies into this. Some of these studies have tried to get the figures on how many autistic people actually identify as ‘not straight’ or ‘not cis’.

Others have tried to compare the number of autistic people who identify as LGBTQIA+ against the number of neurotypical people who identify as LGBTQIA+. Many have focused on the crossover between being autistic and having a trans identity (as these numbers appear to be particularly high when compared with the neurotypical community). Further studies have tried to get to the bottom of the crossover between LGBTQIA+ and autism, to explain it in medical or psychological terms, and to try and answer the question: why?

In the process of doing research for this book, it has become painfully obvious to me that very few of these studies involved autistic LGBTQIA+ people in any real way. One study in particular attempted to draw a line between ‘sexual identity’ and ‘sexual behaviour’, pointing out that many autistic people studied ‘claimed’ to be LGBTQIA+ and yet had never had sex with someone of the same sex (implying that sexuality is based on your sexual history rather than your knowledge of your own attraction and identity). It also suggested that many autistic men may identify as ‘non-heterosexual’ simply because they were nervous about approaching girls.

Not only is this insulting to the many autistic LGBTQIA+ people out there (plus autistic people and LGBTQIA+ people individually), but it’s not reflective of the reality that I have found as a person actively existing, socializing and advocating under the double rainbow. The unfortunate fact is that many of these studies simply fail to recognize that autistic LGBTQIA+ people are real people, living real and varied lives. More disappointingly, however, they never actually address the things that would actually have helped me as a young autistic LGBTQIA+ person. That’s why I decided to write this book.

As a teenager, I desperately needed something that could guide me through life as an autistic LGBTQIA+ person: through working out my identity, coming out to family, friends, colleagues and strangers, finding support, getting involved in the community, and safely navigating friendships and relationships as both autistic and LGBTQIA+.

I needed someone to hold my hand and tell me what to do, what to expect, and to reassure me that it was going to be okay. Or, at the very least, that it wasn’t going to be quite the horror show I had created in my mind.

I came out as bisexual when I was 16. I started identifying as ‘queer’ as well as bisexual when I began getting involved in campaigning at university. I’ve always been a shouty person who wants to change the world for the better. Seeing injustice has always been physically painful for me.

As much as I worked towards being proud of my sexuality, I still found it difficult to find my place in the LGBTQIA+ world. I just couldn’t find where I belonged. I still felt different, detached, as though everyone around me was tapping into something that I couldn’t quite get a handle on.

Then, when I was 23, I got my answer: I am autistic as well. This opened up a whole new door of possibilities for me. As comedian and writer Hannah Gadsby says, my diagnosis ‘was like being handed the key to the city of me’.

For the first time, I understood myself fully. I also understood myself as a queer person fully, and why I had struggled to find my place in the queer world.

In some ways, I was lucky. By coming out years before my autism diagnosis, I had managed to avoid a lot of the denial around sexuality, gender and autism. Nobody ever questioned whether I could or should be queer, or even if I should have a sexuality. That kind of pushback was never a part of my coming out story.

But I always was autistic. I was autistic when I was figuring it out. I was autistic when I was coming out. I was autistic when I was building relationships for the first time.

I was autistic when I tried to go out and about in the queer community. I was autistic while trying to deal with the bigotry and injustice that sometimes come part and parcel with living loudly as a queer person.

And a book like this would have helped make that process so much easier.

So I hope this is helpful to you. I hope that this is at least

a small bit of guidance on the winding road that is figuring

out who you are and who you love. We’re going to look at the whole spectrum of experiences that you might have as an autistic person figuring out and exploring your sexuality and gender. This will include:

• The definition and history of some of the labels people use for their sexuality and gender.

• What attraction feels like and ways to help you figure out your sexuality.

• What gender feels like and ways to help you figure out your gender identity.

• Coming out (telling people about your sexuality and gender) and how to be safe while doing it.

• What it means to undergo gender transition and the different journeys you can take to do it.

• Different types of relationships and how to navigate them (including how to spot, avoid and escape toxic or abusive relationships).

• Understanding consent and having sex safely as an LGBTQIA+ person.

• Being out and about in the LGBTQIA+ community and finding community spaces that work for you.

• How to deal with bullying and injustice, and ways you can make a difference.

Queerly Autistic is published on 21 April 2021 by JKP. It’s available from JKP.com or wherever you buy books.

If you would like to read more articles like this and get the latest news and offers on our books about autism, why not join our mailing list? You may also be interested in our Autism Facebook page or Twitter page.