Editor Christoper Lewis argues the importance of interfaith worship and prayer, particularly in light of current world events.

I guess it is often easier to write a book than to be an author/editor, but Dan and I had to edit this one as we needed insights from actual practitioners of different religions. We were responding to events of all sorts. For example, when there is a crisis and people of different religions feel that they must meet each other to say how sad they are about a shooting or a case of persecution: when Christians are persecuted in Pakistan or Muslims in Myanmar or there is fighting between Buddhists and Tamil Hindus in Sri Lanka. People then wish not only to talk but to pray and maybe worship together. Or, often, religious people want to cooperate in their longing for peace or in their concern for the environment. What are the problems and what are the joys of such occasions? So we set about gathering contributions from Hinduism, African Traditional Religion, Judaism, Jainism, Buddhism, Zoroastrianism, Shintoism, Christianity, Islam, Sikhism, Unitarianism and Baha’i.

Our aim has been not only to learn from people’s views, but also to encourage interfaith worship and prayer. This is a book with a message.

What have we learned?

A lot of views, almost all positive. A couple of our contributors turned out to be very cautious. Typologies are not always helpful, but a sketch of different attitudes among the religious may be useful.

‘Exclusivists’ is a label for those who reckon their own way is the only way to God or to Enlightenment. They may not engage in interfaith contact, and certainly not in prayer. Some see other religions as wrong and maybe as evil, with their followers on paths which do not lead to salvation. If there is contact it is probably with a view to conversion. They often start from a theology of individual redemption (the world is largely fallen with individuals saved through faith) rather than balancing that view with a theology of the creation.

‘Inclusivists’ who see other religions as having value and insight, but their own as the fulfilment, the ultimate truth: all roads lead to…. Many expert people have had that view and done great interfaith work. There is, of course, a lurking sense that one is right and the other wrong.

‘Pluralists’ start from a basis of respect and often have a doctrine of creation as their starting point, although that does not exclude a doctrine of redemption. Other major religions are then seen as paths to the Divine which have been tried and tested. So other great religions are not seen as mistakes. God has allowed them to exist over many years and they express truths in different cultural contexts. There are countless millions who have not been believers in any of the religions mentioned: down history and across geography. Are they all damned?

What does the pluralist believe about his or her own religion? Answer: like falling in love. I may know for sure that my wife is the best in the world. Yet I know that in fact there are others who think in the same way about other wives and that they are not unreasonable. So, I may love Christianity and live with it as wonderful and expressing ultimate truths, while realizing both its drawbacks and cultural conditioning, and being able to value other great religions.

But there are limits to pluralism? We are not ‘all going the same way’; we must recognize difference; the great religions are very different and have been tried and tested over time. Then one must not gloss over bad religion of which there are countless examples in Islam, in Christianity and in all religions. There is good and bad religion and we need criteria for judging. So you can challenge religions e.g. on child abuse or on violence or on autocratic hierarchies. That is mission. But the main evangelistic effort is to one’s own religion and to the secular world.

Looking to the past

It is fascinating to look at the past which is more mixed than people think. There is much evidence of mixing even in the prophet’s own city where Muslims and Jews were able to worship together. There has been much coexistence and some dual allegiance right up to the present day.

The contributions provide insights into the different ways of looking at shared prayer and worship. Buddhists, of course, do not pray, but they can bring a wonderful gift in their meditation; in fact, much of what is now practised as mindfulness is from Buddhism. One of the African Traditional Religion contributions is from Swaziland and there the religion which used to be just dismissed as primitive by missionaries, is held alongside much of Christianity. African Traditional Religion brings an attitude to nature which Christianity has often lacked and also an emphasis on family, past, present and future which is distinctive and corrective.

If human beings are not to self-destruct and be described as God’s failed experiment, great religions have got to cooperate. The actual consequences of religious faith and activity are often absolutely disastrous. I have been reviewing a book on ecclesiology or the nature of the church and it reveals many deeply concerning features: visibly fragmented, morally compromised and often dysfunctional. We must learn from each other.

And yet…as one of our contributors claims, religions could be called the first really international organisations. The actual performance of religions is at the same time both truly and shatteringly disgraceful and also transformative and inspiring. It was the wonderful calm devotion of Moroccan Muslims which made Charles de Foucauld rediscover his Roman Catholic faith. If different faiths are to make an impact in wider society, they must be strengthened by seeking ways of cooperating at their deepest levels, which is the level of prayer and worship.

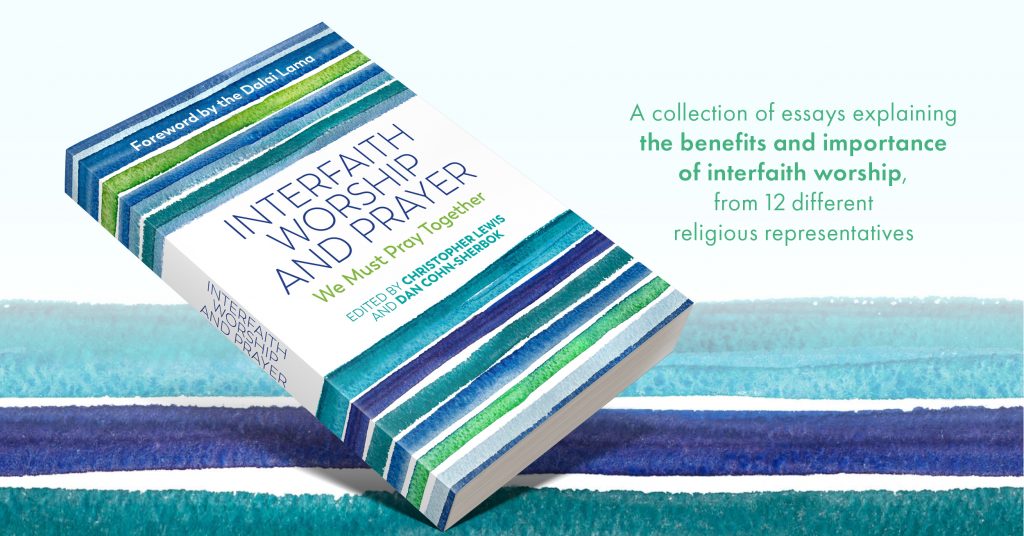

Christopher Lewis is the co-editor of Interfaith Worship and Prayer: We Must Pray Together, alongside Dan Cohn-Sherbok, out on 18th July 2019. Available to pre-order here.