Shibley Rahman completed his PhD in frontotemporal dementia at Cambridge University, commencing a lifelong interest in the timely diagnosis of dementia. In this article he argues for more high quality research into the possible benefits of music therapy for people living with dementia; as well as making the case for the development of dementia care strategies which include the vital insight of people trying to live well with dementia today, so we can improve the experience of care for the many people in future who will receive a diagnosis of dementia.

You can learn about Shibley’s book, Living Better with Dementia, here

It won’t have escaped you, hopefully, that the five-year English dementia strategy is up for renewal at any time now. The last one ran from 2009 to 2014.

Probably the usual suspects will get to command the composition of the new one. “Dementia Friends” has been a great initiative which has taught at least a million people so far about some of the ‘basics’ about dementia, but this ‘raising awareness’ is only part of a very big story.

In my book Living Better with Dementia: Good Practice and Innovation for the Future, about to be published by Jessica Kingsley Publishers, I argue that it is the people currently trying to live better with dementia who should be the ‘champions’ for the future. I believe strongly they should drive policy, not ‘leading Doctors’ or senior members of big charities.

My reasoning is as follows.

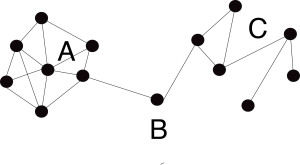

The population at large can be thought of as consisting of many people, represented below as dots.

In a ‘cohesive’ (close) network such as A, members in the network are connected in close proximity. This builds trust and mutual support, discourages opportunistic flow of information, facilitating communication but minimising interpersonal conflicts. A cohesive network might be the hierarchical network of medical professionals.

A ‘sparse’ network (C) is effectively opposite to cohesive networks; but let’s say for the purposes of my example C consists of people with an interest in non-pharmacological interventions in dementia, including unpaid family carers.

In bridging networks, the ‘bridge’ (B) acts between disparate individuals and groups, giving control over the quality and volume of information exchange. I think of politicians such as Debbie Abrahams MP and Tracey Crouch MP, and the All Party Parliamentary Group on dementia at large, as people who can act as the bridges. These people are pivotal for policy formation.

I devoted a whole chapter of my new book to promoting leadership by people aspiring to live better with dementia.

Having all these people involved will improve the thought diversity and relevance of the new strategy for people actually living with dementia

We are currently in the middle Music Therapy Week 2015, dedicated to raising awareness about how music therapy can improve the lives of people with more progressed dementia. It’s no accident I’ve devoted the bulk of one chapter in my book to explain the brain mechanisms behind why music has such a profound effect on people living with dementia.

We, as human beings, all react uniquely to different music – there’s every reason to believe that certain people living with dementia, whether in the community, at home, in residential home, or a hospice, in other words wherever in the “dementia friendly community”, can hugely benefit from the power of music.

“Over the next five years and beyond the NHS will increasingly need to dissolve these traditional boundaries. Long term conditions are now a central task of the NHS; caring for these needs requires a partnership with patients over the long term rather than providing single, unconnected ‘episodes’ of care.”

In Rotherham, GPs and community matrons work with advisors who know what voluntary services are available for patients with long term conditions. Apparently, this “social prescribing service” has cut the need for visits to accident and emergency, out-patient appointments and hospital admissions.

Today sees a wide-ranging, open discussion of music therapy and dementia in Portcullis House, in Westminster. Prof Helen Odell-Miller, Professor of Music Therapy, Director of The Music Therapy Research Centre and Head of Therapies at Anglia Ruskin University, presented significant research findings at the meeting.

I feel music is not being given a fair ‘crack of the whip’ in the current policy. The first English strategy, “Living well with dementia: a national dementia strategy” , was initially launched by the Department of Health, UK in order to improve ‘the quality of services provided to people with dementia . . . [and to] promote a greater understanding of the causes and consequences of dementia’ (Department of Health, 2009, p. 9).

We could have done, I feel, so much more on research into music by now. We could have done much more to increase the number of music therapists in England by now. Maybe some of this is due to ‘parity of esteem’, which has seen mental health play ‘second fiddle’ to physical health.

There are, however, glimmers of hope though, I feel. For example, it was last year reported in the Guardian:

“Overseen by Manchester University, it is part of a 10-week pilot project called Music in Mind, funded by Care UK, which runs 123 residential homes for elderly people. The aim is to find out if classical music can improve communication and interaction and reduce agitation for people in the UK living with dementia – estimated to number just over 800,000 and set to rise rapidly as the population ages.”

Accumulating evidence shows that persons with dementia enjoy music, and their ability to respond to music is potentially preserved even in the late or severe stages of dementia when verbal communication may have ceased. Musical memory is considered to be partly independent from other memory systems. In Alzheimer’s disease and different types of dementia, musical memory is surprisingly robust, and likewise for brain lesions affecting other kinds of memory.

Given the observed overlap of musical memory regions with areas that are relatively spared in Alzheimer’s disease, recent findings may, actually, explain the surprising preservation of musical memory in this neurodegenerative disease. Jacobsen and colleagues (2015) found a crucial role for the caudal anterior cingulate and the ventral pre-supplementary motor area in the neural encoding of long-known as compared with recently known and unknown.

That’s why I believe we should support the British Association for Music Therapy (BAMT), the professional body for music therapists and a source of information, support and involvement for the general public. The title music therapist can only be used by those registered with the Health and Care Professions Council. So there is regulatory capture, if not corporate capture.

This year’s campaign by the BAMT focuses on the instrumental role music therapy has to play in supporting people with dementia and those who care for them. Indeed, the current Dementia Strategy acknowledges that music therapy, as well as other arts therapies, ‘may have a useful role in enabling a good-quality social environment and the possibility for self- expression where the individuality of the residents is respected’ (Department of Health, 2009, p. 58).

Leading research has suggested that music therapy can significantly improve and support the mood, alertness and engagement of people with dementia, can reduce the use of medication, as well as helping to manage and reduce agitation, isolation, depression and anxiety, overall supporting a better quality of life. But very recently Petrovsky, Cacchione and George (2015) have found that there is “inconclusive evidence as to whether music interventions are effective in alleviating symptoms of anxiety and depression in older adults with mild dementia due to the poor methodological rigor”. This reinforces my view that service provision will only be markedly improved if we invest in high quality research, as well as the allied health professionals who can offer high quality (and regulated) music therapy as clinical service.

As I argue in my new book, “Dementia Friends” is great – but we’ve gone way beyond that now. The “Prime Minister Dementia Challenge“, I feel, showed great leadership in prioritising dementia as a social challenge, and the “Prime Minister Challenge on Dementia 2020” follows suit.

As I argue in my new book, “Dementia Friends” is great – but we’ve gone way beyond that now. The “Prime Minister Dementia Challenge“, I feel, showed great leadership in prioritising dementia as a social challenge, and the “Prime Minister Challenge on Dementia 2020” follows suit.

Being honest, we haven’t got a good description of what ‘post diagnostic support’ means, and therefore what it precisely looks like, for dementia. But one thing that is very clear to me that we need to invest in the infrastructure, including research and service provision, to implement living better with dementia as a reality in England. But I remain hopeful that my colleagues in the music therapy world will be able to win friends and influence the right people.

Find out more about Shibley’s book, Living Better with Dementia, read reviews or order your copy here.

One thought