Jenny Drew’s new book Cartooning Teen Stories is full of activities based on comic-making to help young people explore life issues. Read on to learn about how comics can be used as therapeutic tools.

My work brings me into contact with other people who have somehow not been able to take their place in the world. Experiencing trauma, social marginalisation, unmet emotional needs, all contributes to difficulties in being able to make sense of their own narrative within their social context. They just don’t ‘fit in’.

My work brings me into contact with other people who have somehow not been able to take their place in the world. Experiencing trauma, social marginalisation, unmet emotional needs, all contributes to difficulties in being able to make sense of their own narrative within their social context. They just don’t ‘fit in’.

Alfie had started off life this way. He had a diagnosis of attachment disorder due to early abuse from those who were supposed to protect him. He found it difficult to form relationships and regulate his emotions. He’d been refusing to go to lessons – wandering the corridors instead, and sometimes going off site where he’d be picked up by police. When I met with him in school we’d be given a tiny room that was also used as a storage cupboard. It can be very awkward and a little intense, sitting in a cupboard with a complete stranger, expecting them to tell you about their life. They don’t really understand who you are or what you want from them. You’re probably just another adult who expects them to be something ‘better’ than they are. If I ask him direct questions, he shrugs and says ‘dunno’.

He creates a diversion by picking things up, opening drawers, experimenting with how much he can lean out of the window before I freak out. He gets on the floor and sits under the table, facing the wall, drawing on the cracked paint with a pencil. At the end I ask him if he’ll see me again next week. ‘I dunno, depends,’ he says.

He creates a diversion by picking things up, opening drawers, experimenting with how much he can lean out of the window before I freak out. He gets on the floor and sits under the table, facing the wall, drawing on the cracked paint with a pencil. At the end I ask him if he’ll see me again next week. ‘I dunno, depends,’ he says.

The next week I lay out things on the small table – a tiny finger skateboard, some sharpies and a big sheet of paper. When he comes in he immediately grabs the skateboard and pushes it around the room with his fingers. He shows me some ‘tricks’. He seems in a better mood today. Then he picks up a marker and says suspiciously ‘what’s this for?’. I tell him I put those out so he can draw or scribble or write on the paper while we talk. I said I think it’s easier to talk when you’re doing something else at the same time. He picks up a pen and writes his name, in tiny letters in the corner. He looks at me. Then he picks up all of the pens and holds them all tightly in his fist, and with a burst of energy, scribbles across the whole paper until there is no white space left. He slumps back in his chair. ‘Can I go now?’ Of course, I say. He grabs his bag and walks out.

The next session I suggest we play a game. I’ll draw a line or a shape, then you can draw one, and we’ll keep going until we’ve got a picture. As an image of a strange figure with giant orange eyeballs and a purple dog emerges, we start to form the beginnings of a silent shared humour. Each shape I draw is a response to his last one. When I embellish something that he’s started, he gives me a little look and a smile. When we’ve finished I tell him he can give the picture a title.

YOU! HA HA HA!!! He writes, and we both sign our names. He puts the picture in his bag.

What’s the point of all this? We haven’t gotten to the bottom of why he isn’t going to class or why he broke into a farm last week and ran around with a chicken under his arm when he was supposed to be learning geometric equations.

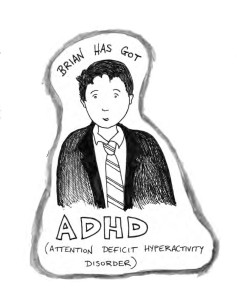

The point is that at an early age, he formed an internal ‘life script’, which offered him the best hope of protection from adults who can’t be trusted. My job is to very carefully and gently challenge that script, before I can do any of the other work with him. In the coming year, he helped me write the story of ‘Brian’, the character in my book who has ADHD. He mapped out his stories with images and scribbles and panel comics, and he made trump cards to identify his feelings and how they begin the paths that lead him to trouble. He shares some of the things he’s made with professionals and carers in his ‘a Team Around the Child’ meetings. He doesn’t say a lot, but he makes his feelings and perspective known through his words and images. He still has ups and downs but I believe that this bit of work has given him the opportunity to change his script and begin to find his voice.

The point is that at an early age, he formed an internal ‘life script’, which offered him the best hope of protection from adults who can’t be trusted. My job is to very carefully and gently challenge that script, before I can do any of the other work with him. In the coming year, he helped me write the story of ‘Brian’, the character in my book who has ADHD. He mapped out his stories with images and scribbles and panel comics, and he made trump cards to identify his feelings and how they begin the paths that lead him to trouble. He shares some of the things he’s made with professionals and carers in his ‘a Team Around the Child’ meetings. He doesn’t say a lot, but he makes his feelings and perspective known through his words and images. He still has ups and downs but I believe that this bit of work has given him the opportunity to change his script and begin to find his voice.

Humans have always told each other stories to make sense of the world. If young people don’t get support to understand their narratives, and they can’t see their stories reflected anywhere else in the world, it will impact their ability to understand who they are and interact with their environment in adulthood. With comics – sequential text and / or images that tell a story – they don’t need to be outspoken, completely literate or good at art. They can explore their world from different angles. Find hidden memories. Express them. Connect with others. In providing this opportunity we can change internal script messages of ‘I don’t matter’, ‘no-one listens to me’, ‘I have nothing to say’. And for the reader – a new way of looking at the world – uniquely through the eyes of the young people so many of us want to help.

View extract: Comic 2 – Brian – The Story of a Young Person with ADHD

ISBN: 978-1-84905-631-1

Price: £22.99

Available now!