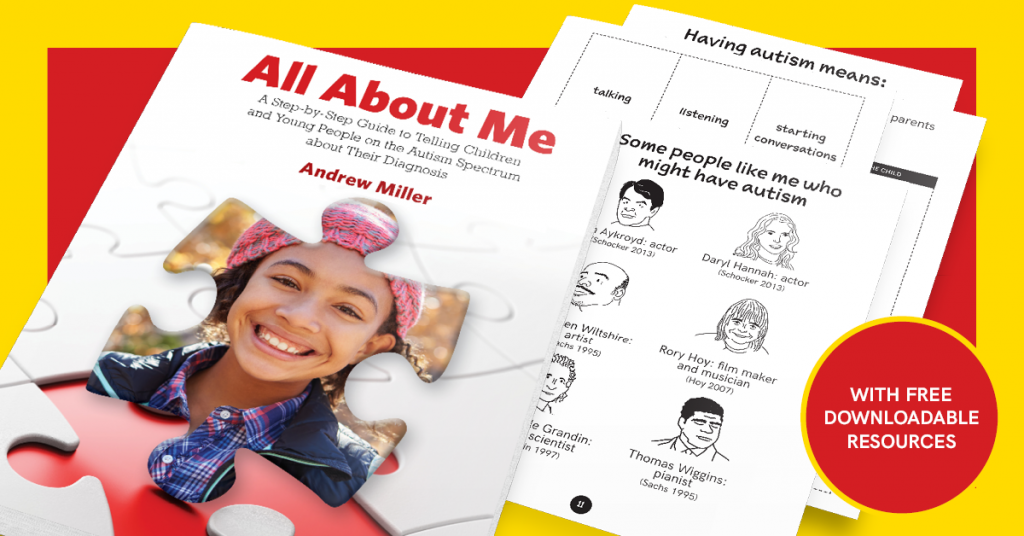

All About Me is an in-depth guide describing the practicalities of introducing a child or young person to their autism diagnosis. It is based on author Andrew Miller’s professional experiences of telling more than 250 children and young people that they have autism. This interview with Andrew was done to discuss the fact that he recently received an autism diagnosis himself at the age of 59, and answer some of the questions that people have asked him about it so far.

What led you to seek an autism diagnostic assessment at this stage in your life?

It wasn’t something that was planned by any means, rather it came about by chance through a classic light bulb moment during a psychotherapy session. Prior to that, I knew that I had significant anxiety issues, hence the course of psychotherapy and my early retirement from teaching. Previous conversations with colleagues working with children with special educational needs had led me to assume that I was probably dyspraxic. At the same time, common themes that cropped up in autism courses, conferences and literature led me to conclude that I presented some behaviours which are often associated with autism. However, none of this seemed to quite add up enough for me to consider that I might actually be autistic.

It was when I was discussing my experiences of being in unstructured social situations, during the therapy session, that I had the sudden realisation that what I was saying echoed what many autistic children had told me about themselves when they were working through the All About Me Programme. At that point I sought the diagnostic assessment since I felt that finding out, either way, was vital to my self-understanding and being able to move forward in my life. In effect, I have the autistic children and young people I’ve worked with to thank for this.

Why do you think you weren’t diagnosed sooner?

There’s no simple answer to this question and I don’t want to lay the blame on anyone for missing my autism. After all, I was born in 1960, so, far less was known about the breadth of diversity within the autism spectrum during my childhood and adolescent years. Moreover, despite a vast amount of effort, I was mostly able to mask many of my differences by imitating others, keeping my head down, behaving passively and blending into the background within a group. While some of my differences (e.g. a childhood speech articulation difficulty) couldn’t be hidden easily, my language and literacy skills and IQ were all judged to be well within the expected ranges for a child of my age. I suppose that meant I didn’t fit neatly within the stereotypical views of how autism manifested in children and young people.

There’s no simple answer to this question and I don’t want to lay the blame on anyone for missing my autism. After all, I was born in 1960, so, far less was known about the breadth of diversity within the autism spectrum during my childhood and adolescent years. Moreover, despite a vast amount of effort, I was mostly able to mask many of my differences by imitating others, keeping my head down, behaving passively and blending into the background within a group. While some of my differences (e.g. a childhood speech articulation difficulty) couldn’t be hidden easily, my language and literacy skills and IQ were all judged to be well within the expected ranges for a child of my age. I suppose that meant I didn’t fit neatly within the stereotypical views of how autism manifested in children and young people.

Again, as an adult, my achievements have perhaps exceeded societal expectations of what autistic people might be capable of. For example, I went to university, had a career in teaching – which included several senior leadership posts and being an autism advisor-, had a book published, drove a car, travelled extensively, owned a home and have been married with a child for nearly 25 years.

How did you react to the diagnosis at first?

Receiving my diagnosis has definitely turned out to be a life changing event. It’s been 3 months now and I am proud of my autism but I won’t pretend that it’s discovery hasn’t had some significantly destabilising and confusing effects. For instance, it just seems really strange that after having told so many children about their autism I missed it in myself. Knowing about my autism now perhaps explains why I was attracted to working with autistic people in the first place.

Fixating my thoughts intently on specific special interests, personal goals or particular issues and prioritizing these above other things seems to be a major part of my personal autism profile. This can bring many benefits. I have been able to focus on achieving some very challenging things that required a tremendous amount of endurance, such as overcoming morbid obesity, running marathons, becoming a published author and quickly learning to converse in foreign languages. On the other hand, episodes of being constantly preoccupied and bombarded by intrusive negative thoughts has taken a huge toll on my emotional well-being.

Overall, I seem to have accepted and embraced my diagnosis positively up until now. I definitely feel calmer than I have for years. I think that this is mainly down to my prior knowledge of autism coupled with my experiences of teaching autistic children and having been able to positively introduce so many of them to their diagnosis through All About Me. When I started to develop the programme my key aim was to come up with an initiative that I would have been happy to have been guided through myself if I had been the autistic child that it later turned out I had been.

Who have you told about your diagnosis so far and what is your attitude towards sharing this information?

Starting with immediate family members, I quickly informed most of the people I am familiar with and come into regular contact with. Now I am completely open about my diagnosis, having announced it both here and on social media. I am a member of the governing board of an autism special school and had absolutely no hesitation in sharing my diagnosis with the whole school community. I have been encouraged by people’s initial responses to this news as they have been accepting and supportive.

When it comes to telling others on a day-to-day basis, I generally make that decision according to how relevant or convenient them knowing would be for either of us at the time. I also try to weigh up whether they can be trusted to use the information positively and respectfully. Disclosure was useful, for example, during an eye test when I needed to explain why my sensory profile meant that I needed lenses that took into account my differences in central and peripheral vision. I knew that the optician was likely to be a safe person to have this conversation with as she was bound by her professional code of conduct.

In All About Me, each child creates a personal headline sentence to describe what being autistic means for them: what do you think a sentence written for you should say:

The headline sentence in a child’s All About Me booklet is meant to provide them with a precise, visual and concrete personalized matter of fact summary of what being autistic means for them. This is framed in the context of their own overall strengths and challenges so I think that in my case it would say something like this:

The headline sentence in a child’s All About Me booklet is meant to provide them with a precise, visual and concrete personalized matter of fact summary of what being autistic means for them. This is framed in the context of their own overall strengths and challenges so I think that in my case it would say something like this:

Autism is a word that can be used to describe a person like me who might be:

good at focusing their attention on their special interest and goals…

…and finds it harder to recognize what other people might be thinking, feeling or needing.

How do you expect the discovery of your diagnosis to impact on your future life?

I am hoping that my diagnosis will positively renew and strengthen my relationships with those closest to me. Ideally, we will use this new information to learn to better understand, accept and live with each other’s different ways of thinking and communicating without any of us having to compromise our individuality. I am optimistic too that the new insight my diagnosis brings will enhance the quality of any future work I do with autistic people and those around them.

Finally, one of the main recurrent messages in my book is that that accepting, understanding, internalising and learning to live with an autism diagnosis can be extended processes. Bearing this in mind, my responses to some of the questions in this article are more than likely to evolve over time.

If you would like to read more articles like this and get the latest news and offers on our books about autism, why not join our mailing list? We can send information by email or post as you prefer. You may also be interested in liking our Autism, Asperger’s and related conditions Facebook page.