Continued from Part 2: Dynamic Play Therapy, Harnessing the power of collapse and renewal »

In the final Part of our interview with Dennis McCarthy, author of the new book A Manual of Dynamic Play Therapy, he shares some cases from his own practice in which his approach, Dynamic Play Therapy, was successful in facilitating positive changes in children with emotional and behavioural difficulties.

How should this book be used?

A Manual of Dynamic Play Therapy should be used as carte blanche permission to parents, educators and especially psychotherapists working with children to trust play. I hope the book will let them know why this is so if they don’t know this, and encourage those who already understand play’s necessity to feel affirmed in what they do, and to develop methods that emerge out of the overlap of their play and that of the children they work with. I hope readers will become less afraid of rocking the boat of authority that urges us to make the child talk in adult terms about what the adult world deems important to them. Rather than having children be obedient patients, I want to encourage us to attempt in our work to foster true self-possession, knowing how very hard it is to achieve. I urge us all to fight the tendency to negate emotion, to negate aggression, to negate anything and everything that pulsates with life and therefore stirs things up. How incredibly conservative the profession of play therapy has become, at least in the U.S.! We must free it from the constraints that have hobbled it. I hope this book affirms the centrality of play and reminds all of us how very powerful a vehicle for growth and change it can be.

A Manual of Dynamic Play Therapy should be used as carte blanche permission to parents, educators and especially psychotherapists working with children to trust play. I hope the book will let them know why this is so if they don’t know this, and encourage those who already understand play’s necessity to feel affirmed in what they do, and to develop methods that emerge out of the overlap of their play and that of the children they work with. I hope readers will become less afraid of rocking the boat of authority that urges us to make the child talk in adult terms about what the adult world deems important to them. Rather than having children be obedient patients, I want to encourage us to attempt in our work to foster true self-possession, knowing how very hard it is to achieve. I urge us all to fight the tendency to negate emotion, to negate aggression, to negate anything and everything that pulsates with life and therefore stirs things up. How incredibly conservative the profession of play therapy has become, at least in the U.S.! We must free it from the constraints that have hobbled it. I hope this book affirms the centrality of play and reminds all of us how very powerful a vehicle for growth and change it can be.

The book can be used as a manual as the title implies. Having begun practicing play therapy with absolutely no guidelines, I hope the guidelines suggested in the book will help those just setting forth or those struggling to find their way forward. These methods and materials have proved highly successful, not only in my own practice but in that of many of the therapists I have trained and supervised over the years. In a sense it is the manual I never had.

Can you share some examples of successful application from your own experience?

I have a few recent cases to share. They fall under two headings; the suppressed child and the dysregulated child.

Case 1: The suppressed child – Charles.

In the category of the suppressed child, I want to share the brief work done with a ten-year-old boy I will call Charles. I have seen Charles three times thus far. Charles was adopted at birth by two depressed parents. The adoptive father had a history of physical abuse in his own childhood. His father has been in treatment with me for the past year. Part of his work has been coming to understand the needs and behavior of his children in a new and healthier light. When I first met him he would fly into rages at them regularly and then withdraw into himself. His rages were those of a cornered animal and he was responding to his children in self-defense.

After he had been coming for some time and doing much better regulating his emotions, his son asked to come with him to therapy. In that meeting they talked about his dad’s anger, fought playfully with some foam bats I have and then made a world in the sand, each using one side of the box. What I noticed in the son’s sand world was how flat and empty it was. There was literally no life in it, whereas his father’s world, though not terribly imaginative, had numerous animals and people. In fact, his son Charles had a flat affect and seemed repressed rather than depressed. Was this due to the atmosphere at home? It made sense that with two depressed parents, one of whom could be quite rageful, he would subvert his own natural aggression along with his vitality.

Some months later Charles asked to come alone to see me. He came ostensibly to talk about his father. I think he had been fascinated by the sand, as well as the potential for expressing anger and aggression with me. This time his sand world was much more complex. He spent a long time making a huge mountain and hollowing out the inside. This was quite a feat and it took great patience and skill on his part. I am actually not quite sure how he managed it. Once the hollowed-out mountain was done, he made a very small opening in it with a very defined pathway leading to it. He placed trees around it and a few animals. The world was described as “the mountain palace of a people who were now somewhere else”. There was an air of mystery to the allusion to the people and the remnants of their life there. The mountain felt and looked like a pregnant belly. Despite being empty, it felt full. Charles also spent time venting his anger at both his father and his teacher at school who was very strict.

In my most recent session Charles’ sand world depicted a huge open-air arena. People lined the tops of the walls of it watching knights battling below. There was a king watching too, and he was being protected by soldiers. Charles made this world with the same intense deliberation as his previous one. But the mountain had opened up and become a place of battle and was also filled with people. At his session’s end his father noted how the world seemed like the opposite of his previous one. His scene didn’t fall apart but rather it unfolded. Charles was coming to life before my very eyes, birthing a new way. The diminishment of his father’s rage, plus his having an opportunity to articulate the inner stasis and evolve it, has begun to make him a happier and more assertive child at home and in school.

Case 2: The dysregulated child – Sam.

Over the past two months I have accepted into my practice several extremely dysregulated boys. After saying yes to the parents, I came home and asked my wife if I was crazy go have done so. Why at my age would I agree to see four boys who, according to their parents, were extremely out of control? In fact these boys have been a joy to work with and loudly affirm the material in the book.

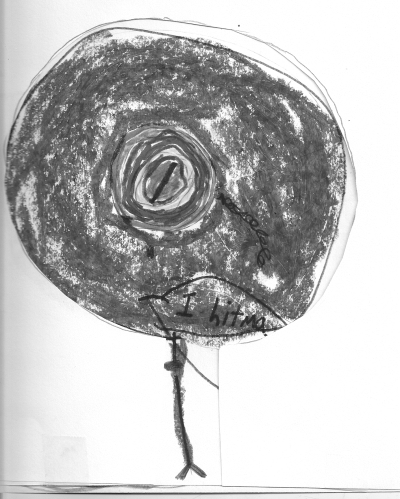

A four year old I will call Sam was brought to see me a month or so ago due to an increasing tendency to “get stuck” in situations and have prolonged tantrums when his parents tried to shift him from what he was doing. This “getting stuck” manifested itself in almost any transition. He would bite and lash out in these moments with increasing intensity.

Sam had a very long and traumatic birth that necessitated having his shoulders broken to emerge. His mother said in our intake that Sam was born angry. How else might a child respond to such an entrance into this world? I think Sam might have some neurological or sensory integration issues and he will have an evaluation by a pediatric neurologist in the coming weeks. But in our sessions several interesting things have happened. First, Sam has created an ongoing and evolving story in the sandbox. In his first session his sand story showed one side (his) which he referred to as “the bad side” and which was filled with monsters and dragons. The other side, which was the good side, had one small monster on it. I was put in charge of this side. Nothing happened other than setting the stage, so to speak. The bulk of his play happened elsewhere in the space. In his second scene, the sides were a bit more balanced and they were both “bad”. By the third scene the bad side comprised the whole box and the focus of the story was less about “badness” than about how they were living. A pool was made and a tower built and one monster that was made up of flames kept diving into the pool from atop the tower. Then the monsters all withdrew underground. In the end all were covered up with sand and the box looked almost empty. This withdrawal into the sand’s depths felt significant.

Most of Sam’s sessions have involved him playing very intensely with a variety of materials with me mirroring him and also provoking him in subtle ways, urging him to shift. For example, in his first session, he attempted to paint and each time he dipped the brush into the paints he got stuck in the satisfying sensation of the brush in the gooey paint. He wanted to actually use the paints, yet the sensate experience threatened to win out. My job was to affirm his play and attempt to dislodge him at the same time. In our last session he spent time banging on some drums and chimes I have with a large stick. He’d grit his teeth with each bang and he seemed to be attempting to tolerate the intensity that he himself was creating. He had a hard time stopping the banging even though it was annoying him. I tricked him into periodically experimenting with soft bangs, which created a whole different sound and sensation. After doing this a few times with great satisfaction, he laughed and leapt into my arms and gave me a huge hug. He seemed thrilled to have been tricked into a new experience. It was after this that he went back to the sandbox and had his monsters withdraw into the sand.

This burial of the monsters felt like an establishment of filter. The monsters were now declared “safe” by Sam. Safe from whom?, one might ask, as one would not think monsters in need of protection. I think the answer is safe from themselves. If the monsters are in fact Sam’s own impulses and emotions in their dysregulated form, which for him they were in that moment, then the sand was indeed acting as a regulator for these. Amazing!

After my first meeting with Sam I had urged his parents to see his behavior in a different light – as happening due to dysregulation an organic level, rather than simply him acting out or being “bad”. I also urged them to spend “floor time” with him in which they could mirror his play and really join him in it. They admitted that this never happened and they began to connect with him on this level.

After several weeks his parents have reported a much happier, “softer” child at home who is getting stuck much less. When he does get stuck he lets his parents help him get unstuck. I trust this will continue to improve with some steps backward perhaps. I only just now realized the association with his “getting stuck” in his play and his having been stuck in the birthing process. The synchronicity of the two feels important. I think both his parents and my spending time with him on his energetic level using his play language has been the key.

I have worked with many hundreds of Sams. Once the intensity of their own energy becomes more modulated in their play they become more regulated in their overall functioning. The mix of mirroring and simultaneously offering a new way can be a pivotal experience for many children.

Case 3: The dysregulated child – The Twins.

At the same time that I said yes to Sam’s parents I also agreed to see two twin boys whose mother was battling a virulent form of breast cancer. I am quite sure she sought me out as an ally for her sons and her husband in case she died. Even prior to her diagnosis the boys had been very dysregulated. Had they seen a pediatric neurologist they would have been diagnosed with ADHD. The volume of their voices was incredibly loud, their bodies seemed to tremble with energy and one of the two reacted strongly to loud noises. The family had recently moved from an urban setting to a rural one. The boys had begun public school and on their first day they had bitten both the principal and their teacher.

When I began to work with these boys they had just begun sleeping in their own beds for the first time. I recommended this even before I met with the boys. The “family bed” can be a boiling pot for the psyche, and in these boys’ case I think it was part of what was charging them up. Given their mother’s illness, it was especially important that there be more boundaries set. It is hard to know how much this action alone accounted for the major shift in their behavior that has occurred since.

The boys came separately and on separate days and both entered my office with a level of intensity that was impressive. Initially they were in almost constant motion, yet they were also very drawn to the sandbox. The box became the center of our work, literally. Each boy kept an ongoing storyline in it from session to session. At first their play seemed to fall apart quite easily. In fact it was difficult for things to stay together at all, not because they intended this but simply because they were so dysregulated. But things quickly coalesced. One of the boy’s worlds were comprised of monsters fighting knights and he definitely identified with the knights. His brother’s worlds depicted battles between a group of samurai at war with a large family of dragons. He was aligned with the dragons and I was assigned the role of samurai.

In their first two visits they were in motion the entire time, with me attempting to join them in their moving. I didn’t always mirror their actual moves since these boys were able to do things I am no longer able to, such as cartwheels and elaborate falls. But I was in sync with them energetically and they sensed this. They loved that I was aligned with them in their wildness, even as I attempted to lure them into play that might better regulate them. By our third visit they were both much calmer, much less loud vocally. All of the energy was now in the sandbox and the play that ensued therein. This play was very intense but because it involved other creatures acting out their dysregulation, they themselves were not.

Initially when the boys came to see me I could hear them coming from a few blocks away. They began to shout my name out long before they reached the building where my office is. It was both charming and alarming. But now, six weeks later, they arrive and sit with their mother reading in my waiting room. They leap up when I open the door but they don’t seem ready to explode.

I don’t know what life has in store for these two boys. Their mother is struggling with her cancer just as their father is struggling to better mirror his sons and not label them as “bad”. In their own beds with new allies in the quest for healthy self-control, they seem to be making great headway. Their teacher tells me they are now a joy to have in class and that they are remarkably empathic towards their peers. I assume these traits were always there but were trumped by the intensity of their dysregulation.

I think all of us are waiting to be found, waiting to be reached by another. This has been my experience as both patient and therapist. Each child and adult I have ever worked with seemed to be hoping I could lure them out of where they were stuck, lure them into finding a new way of being, even as they may have fought me to stay stuck. The paradox of this is part of what makes the work dynamic. The longing for change and the resistance to it are potentially the catalyst needed to bring about change, if we are able to tolerate and use this. Again, paradox is the essence of metamorphosis.

Copyright © Jessica Kingsley Publishers 2012.