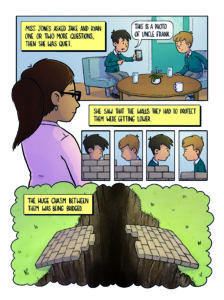

When writing the text for What are you staring at?, a graphic novel about restorative justice in a school setting, I couldn’t resist taking a side-swipe at the antiquated system of school detentions, as a repost to the endlessly repeated rhetoric calling for ‘discipline’ to be brought back into the nation’s schools. By pointing out that more often than not, slapping a detention on a young person for wrong-doing is actively counterproductive, I hope to illustrate how ineffective a punitive system is for resolving behavioural issues or engendering self-discipline within a school community. In one of Joseph Wilkins’ most evocative images, our protagonist, Jake, is seen sitting alone in a large classroom. He is serving a detention for punching Ryan, a pupil in the year below, and we see him simmering with anger and resentment at the injustice of it all. At this point in the book, no one has taken the trouble to tease out the story behind his violent behaviour, and because the punishment hurts (as it is designed to) he is minded to take revenge on the very person he harmed in the first place – namely the innocent Ryan – for being the ongoing cause of his pain. Precious little scope there for reflection, understanding, resolution or healing.

When writing the text for What are you staring at?, a graphic novel about restorative justice in a school setting, I couldn’t resist taking a side-swipe at the antiquated system of school detentions, as a repost to the endlessly repeated rhetoric calling for ‘discipline’ to be brought back into the nation’s schools. By pointing out that more often than not, slapping a detention on a young person for wrong-doing is actively counterproductive, I hope to illustrate how ineffective a punitive system is for resolving behavioural issues or engendering self-discipline within a school community. In one of Joseph Wilkins’ most evocative images, our protagonist, Jake, is seen sitting alone in a large classroom. He is serving a detention for punching Ryan, a pupil in the year below, and we see him simmering with anger and resentment at the injustice of it all. At this point in the book, no one has taken the trouble to tease out the story behind his violent behaviour, and because the punishment hurts (as it is designed to) he is minded to take revenge on the very person he harmed in the first place – namely the innocent Ryan – for being the ongoing cause of his pain. Precious little scope there for reflection, understanding, resolution or healing.

If you ask most secondary school teachers if detentions are used in their school, the answer is a resigned; ‘Yes.’ If you ask whether they work, the answer is an equally resigned; ‘No.’ Usually, if something fails to deliver on its aims, it is changed or scrapped, but unless I am missing something, ’evidence-based practice’ doesn’t seem to apply when it comes to detentions. They don’t seem to have moved on since I was at school myself back in the 1970’s, or was a young teacher in the 1980’s.

If you ask most secondary school teachers if detentions are used in their school, the answer is a resigned; ‘Yes.’ If you ask whether they work, the answer is an equally resigned; ‘No.’ Usually, if something fails to deliver on its aims, it is changed or scrapped, but unless I am missing something, ’evidence-based practice’ doesn’t seem to apply when it comes to detentions. They don’t seem to have moved on since I was at school myself back in the 1970’s, or was a young teacher in the 1980’s.

A few years ago my colleague Jo Brown and I tried an experiment in a couple of local secondary schools which we called ‘reflective detentions’ (Jo is the Oxfordshire Anti-Bullying Co-ordinator and an experienced restorative practitioner and trainer). Each week we cut a deal with the pupils in detention that they could either attend the standard hour of thumb twiddling or enforced written work, or opt for a 45 minute ‘reflective detention’ with us, providing they promised to participate if they chose the latter. Although the coercion and blackmail involved meant that our restorative credentials were in tatters before we even began, once we had a bemused group of pupils sitting in a circle with a talking piece, and made it clear that we were there to listen and to learn with them, we usually found the children remarkably receptive to engaging in a frank and open conversation.

We ran the conversation along Belinda Hopkins’ 5 restorative ‘themes’ (outlined at the back of What are you staring at?). Often the whole edifice of the detention system collapsed with the first question; ‘What happened that led to you being here?’ Frequently pupils had no clear idea of the reason for their detention. Some had forgotten what had happened (which was usually several days in the past, since detentions were often themed and/or organised on set days). Many were confused about the exact nature of their alleged misdemeanour, or disagreed with the way it was represented by the school. Some had been given a detention without being told at the time, only finding out when their name appeared on a list. Rarely had there been a decent conversation with the person handing out the punishment, either to talk about what rule was broken or to determine what might repair any harm done and ensure that the wrong-doing wasn’t repeated. Little surprise thenthat most of the detainees we met were serial offenders.

The turning point in a reflective detention usually came when the group explored restorative theme 3. Jo and I would create concentric circles on the floor, using masking tape to represent ‘ripples of harm.’ We then asked the pupils to think of someone who was affected by their behaviour, and invited them to turn the room into a 3-D sculpture by standing on the ripples, and assuming the role of the person they had identified. It was poignant to witness the insight and empathy expressed as a pupil became their teacher, saying what it feels like when their carefully prepared lesson is disrupted by a late arrival; being their parent receiving the call from school to say that they have been in trouble again; playing the bus driver trying to drive safely while a fight is breaking out on board, or taking the role of the caretaker discovering yet more damage to school property.

The turning point in a reflective detention usually came when the group explored restorative theme 3. Jo and I would create concentric circles on the floor, using masking tape to represent ‘ripples of harm.’ We then asked the pupils to think of someone who was affected by their behaviour, and invited them to turn the room into a 3-D sculpture by standing on the ripples, and assuming the role of the person they had identified. It was poignant to witness the insight and empathy expressed as a pupil became their teacher, saying what it feels like when their carefully prepared lesson is disrupted by a late arrival; being their parent receiving the call from school to say that they have been in trouble again; playing the bus driver trying to drive safely while a fight is breaking out on board, or taking the role of the caretaker discovering yet more damage to school property.

Part of the restorative detention ‘deal’ was that whilst the pupils were asked to come up with a plan to address their behaviour, they could also make suggestions for how the school could learn from what had gone wrong. These ideas we passed on to the SMT. One of the challenges as outside visitors was to ensure that the plans and suggestions (which were usually sensible) were acted on by both sides.

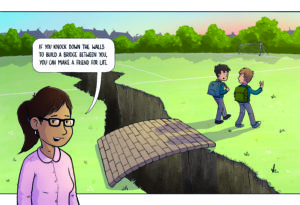

As my work priorities changed I moved away from working in schools, and my dalliance in the murky world of detentions  came to an end. I will never forget the power of restorative justice when applied in a school setting. The approach is founded on respect and honesty, active listening and open curiosity. It avoids judgement, is neutral and impartial, inviting pupils to come up with their own solutions to issues that concern them. Through this creative process comes a sense of empowerment, ownership and community, and a self-discipline that lasts beyond the school gate. I am sure that a school where restorative justice is fully embedded and in its life blood can do away with detentions altogether, can consign them to the scrap heap to follow caning and standing in the corner. My hope is that, in sharing Jake and Ryan’s restorative journey – illustrated with Joseph Wilkins’ gorgeous cartoons – What are you staring at? provides a useful tool for pupils and teachers in driving that transformation.

came to an end. I will never forget the power of restorative justice when applied in a school setting. The approach is founded on respect and honesty, active listening and open curiosity. It avoids judgement, is neutral and impartial, inviting pupils to come up with their own solutions to issues that concern them. Through this creative process comes a sense of empowerment, ownership and community, and a self-discipline that lasts beyond the school gate. I am sure that a school where restorative justice is fully embedded and in its life blood can do away with detentions altogether, can consign them to the scrap heap to follow caning and standing in the corner. My hope is that, in sharing Jake and Ryan’s restorative journey – illustrated with Joseph Wilkins’ gorgeous cartoons – What are you staring at? provides a useful tool for pupils and teachers in driving that transformation.

Click here to find out more about What are you staring at?

2 Thoughts